Chaos or Stability

This piece originally appeared in Issue 2/2017 of New Eastern Europe. Subscribe now.

May 16, 2017 -

Marcin Kaczmarski

-

Articles and Commentary

Reluctance and resistance towards the West’s domination in global politics has fuelled Russian-Chinese relations for the past two decades. Yet their responses and long-term expectations differ significantly. Russia appears to relish the West’s internal difficulties, embracing the populist and anti-globalisation turn. China, on the other hand, emerges as a staunch supporter of globalisation, viewing the turmoil within the western political landscape with the mixture of Schadenfreude and genuine concern.

Two views on globalisation

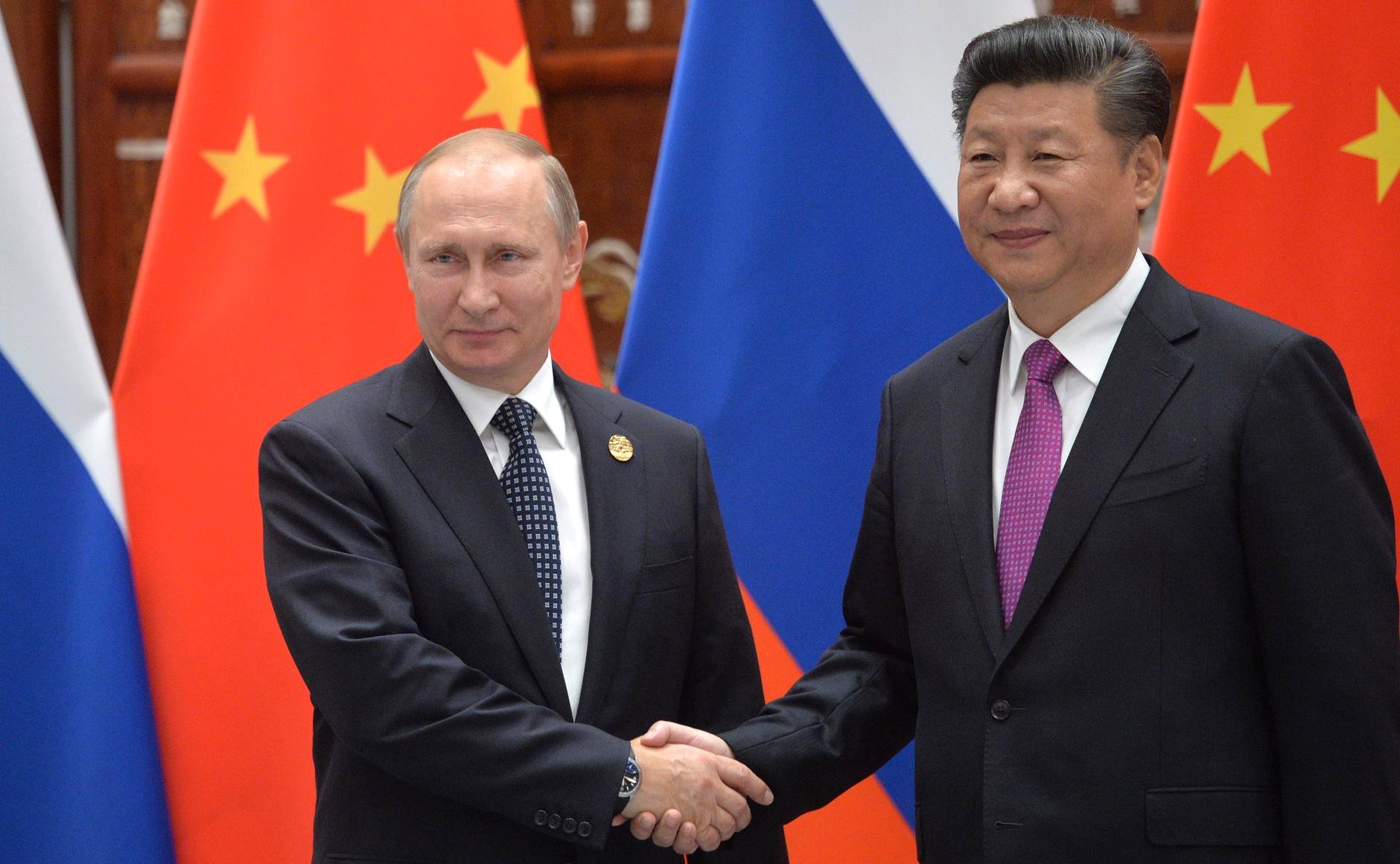

Recent speeches delivered by Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping respectively illustrate the difference between Russia and China’s attitudes and expectations. Xi emerged as a key champion of globalisation and free trade, while we can see that Putin aspires for the title of an anti-globalisation, anti-mainstream chief rebel (although rivalled by Donald Trump following his US presidential election victory). Speaking at an annual gathering of Russian and international experts on post-Soviet politics last October, Putin lambasted globalisation. He depicted it as a project in crisis, led by the selfish elite who have left the majority to remain impoverished and frustrated. Multi-culturalism is also failing, particularly in Europe, according to Putin. Xi Jinping, in turn, offered an authentic defence of globalisation. In his speech at the World Economic Forum in January this year Xi argued that globalisation cannot be blamed for all the world’s problems and warned that a reversal of globalisation is unachievable: “Any attempt to … channel the waters in the ocean back into isolated lakes and creeks is simply not possible.”

These differences cannot be reduced to mere rhetoric. Russia cherishes the growing political-economic chaos inside the West and, according to numerous commentators, goes as far as actively promoting destabilisation. The Russian elite did not hide its satisfaction in Trump’s victory in the US election. The Kremlin also cheered the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union, thus seeing it as the first step to further unravelling of Europe’s post-war political and economic project. Over the years Russia has established a network of contacts with Europe’s far-right and, to a lesser extent, far-left political parties, building its influence among such forces.

In contrast, China has opted for stability and incremental change. Beijing was in favour of the UK remaining part of the EU. Having repeatedly declared its support for European unity, China denounced the rise of populist forces throughout Europe. Regarding the US presidential election, voices in China remain divided. State media presented Trump’s controversial campaign and his subsequent victory as the ultimate proof of democracy’s inherent weaknesses. Although Hillary Clinton was not particularly liked in Beijing – due to her contribution to the US pivot to Asia policy – her election victory would have brought much more predictability to Sino-American relations.

Why do Russia and China seem to have very different approaches to globalisation and the West? These differences may seem surprising, considering both nations share many similar views on the global scale. Both states jealously guard their sovereignty, understood as a carte blanche in domestic politics, and suspect the West of constantly plotting a regime change under the banner of spreading democracy and human rights. Both states pick and choose norms of international law which they are ready to obey, especially with regards to their neighbourhoods. Yet one of these regimes expects to thrive as a result of the deepening chaos while the other tries to maintain at least some degree of international stability.

Russia’s preference for uncertainty

The shortest answer to Russia’s preference for instability is that it has so little to lose from unpredictability in the West. Unlike China, which has made enormous leaps over the last three decades and has benefitted from western-led globalisation, Russia has not gained very much. Its first transition, after the fall of the Soviet Union, saw the ideas of a rule-based, free-market economy and political democracy in the eyes of the Russian society and elite. It took Russia two decades to join the World Trade Organisation (WTO). While being a member of the G-8, Moscow was marginalised when it came to debating financial and economic issues. It never joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a club of developed nations. Arms and energy resources turned out to be Russia’s only genuine assets when looking for its niche in the international division of labour.

Beijing may not like western liberalism and its emphasis on human rights and democracy, but it cannot deny that the West’s opening of the global economy paved the way for its meteoric rise. Moreover, Putin’s government does not base its legitimacy on economic growth to the same extent as the Chinese Communist Party. In the 2000s Russians traded political freedom for a higher quality of life, while in the current decade the social contract between the Kremlin and Russian society is much more based on great power identity and foreign policy successes. Similarly, European unity has not brought about any expected benefits to Russia. Rather it has been an obstacle for the Kremlin in terms of its pursuit of political and economic agreements with individual European states. As the case of energy (gas exports in particular) demonstrates, the EU’s unity even if far from being perfect became a major stumbling block for Gazprom. The Russian company faced accusations of using its monopolistic position, long-term contracts were blocked and its access to pipelines limited. Had it not been for the EU’s unanimous decision, a number of European states would have forgone Crimea long ago and lifted sanctions imposed on Russia in the aftermath of the Ukraine crisis. From this perspective, Brexit not only offers short-term gains, such as drawing the EU’s attention away from Ukraine, but also makes the prospect of European disunity more likely.

The Kremlin’s support for European populists, anti-establishment and far-right parties also carries little risk for Russia. The conservative ideology embraced by the Kremlin since Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, the defence of traditional values and religious roots of European civilisation, disdain for the EU, and the network of ties with radical parties makes Russia less vulnerable in the face of the rise of populism throughout Europe. Leaders of many of these movements openly declare support for Putin’s “strong leadership”, see Russia as the last bulwark against the debasement of Europe and identify themselves with Russia’s anti-American foreign policy.

The victory of Donald Trump – even if we assume Moscow played no role in its outcome – generates a luring vision of a long-expected grand bargain between Russia and the US. Moscow can realistically count on the lifting of sanctions as well as some form of recognition of Crimea’s annexation. Even if the two sides fail to fully accept “the deal”, the chaos which Trump’s election has already unleashed in the West will help Russia achieve its long-term goal of dividing transatlantic relations. Trump’s ambiguous position on NATO and his open dislike of the EU can be expected to generate a rift between the two shores of the Atlantic, not seen since the 2003 war in Iraq. At the same time, Trump’s protectionist economic policy will not do much harm to Russia, given the low level of bilateral trade and investment.

Russia’s political leadership recognises a number of potential gains from the West’s deepening crisis. Instability inside the West makes it easier for the Kremlin to blame the outside world for Russia’s own failures, as well as enabling it to mobilise popular support against the new world “disorder”. It would become easier to divide the West by cherry-picking potential partners. Russia is ready to embrace an anti-globalist movement, stir up discontent and fear against supranational bureaucrats, global oligarchs and global corporations. The invocation of terms such as “the simple man” and the “silent majority”, allegedly disenfranchised by their own elite, portrays Russia as markedly different from the allegedly corrupt western elites, detached from their own societies.

China on the losing end?

China finds itself in a completely different position. The West’s decline may also bring China’s continuous rise to a halt. Beijing has much more to lose than its counterpart in the Kremlin, and not only because the EU and US are China’s number one and two trading partners. While drawing some advantages from divisions within the EU, China remains largely supportive of European integration. The euro offers a counter-balance to the hegemony of the US dollar, and the EU is much more willing to make room for China in the international order –as was demonstrated by the massive application for the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Meanwhile, anti-establishment parties throughout Europe see China’s economic expansion as one of the major culprits for Europe’s economic stagnation and job losses. The European Commission’s anti-dumping tariffs, targeting Chinese steel production, are the first signs of protectionism; and Beijing expects that more protectionism may dominate Europe’s economic policy if far-right and far-left parties seize power across EU member states. For China, the success of anti-globalist parties in the 2014 elections to the European Parliament was the first warning sign.

The result of the Brexit referendum further illustrated potential losses for China. The new British government with Theresa May at the helm, which replaced the Sinophile team of David Cameron and George Osbourne, almost deprived China of its first nuclear power investment in the developed world: Hinkley Point. The new prime minister put her predecessor’s decision on hold, demonstrating reservations towards foreign investment in strategic sectors. It remains unclear whether it was pressure exerted by China that made May reconsider her decision, but the open letter from the Chinese ambassador to the UK left little doubt that Beijing would retaliate should London block the investment. Nonetheless, it was highly plausible that China could have suffered losses there.

The same logic applies to China’s relative preference for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump. It took Trump just a few tweets and one phone call with Taiwan’s president to undermine the foundations of Sino-American relations. Trump appears to disregard cautiousness towards Beijing and aims to use the One China policy – according to which Washington does not maintain official ties with Taiwan – as a bargaining chip. And, moreover, his anti-free trade rhetoric is aimed directly at China. A trade war would undermine Chinese exports, especially given that the US is the largest external market for China and the biggest source of its trade surplus. Even a possible breakdown of the American system of alliances in East Asia, which would strengthen Beijing’s hand in regional geopolitics, may be expected to bring as many challenges as benefits. If Trump were to follow through with his threat to dump America’s Asian allies (and it is at least a possibility), other states, such as Japan, could embark on re-militarisation.

The Chinese Communist Party, as much as it can despise western democracy, needs the capitalist system to remain in place. China relies on open trade and stable markets, as well as on the growing, or at least not declining, wealth of western consumers. It needs a conducive external environment in order to sell its whole range of goods, from low- to high-end, such as high-speed trains, to export the overcapacity of its industry and to invest from its overflowing coffers of US dollars. In other words, China needs another wave of globalisation and has to prevent other states from closing themselves off and building fences.

A responsible great power

Different responses to the challenges relating to globalisation and the West’s domestic problems can be expected to lead to differing roles in global politics undertaken by China and Russia. For years the West saw the former as a free-rider. China benefitted from the West without paying much in treasure or blood. With Brexit, Trump and growing populism in Europe, China is forced to defend globalisation. At the same time, it is even more determined than before not to share western values – namely, liberal democracy.

Recent developments in the West have only reinforced the belief of the Chinese elite in the efficiency of the current Beijing regime. It offers both political reassurances for an open global economy and has begun to shoulder some responsibility, e.g. providing an increasing number of troops for peacekeeping missions. It remains an open question as to whether it is possible to reconcile support for liberal internationalism abroad while cracking down on opposition at home. If China succeeds, perhaps it will also achieve something the West has failed to do – convince Russia that the international order is conducive to its own interests.

Marcin Kaczmarski is an adjunct professor at the Institute of International Relations at the University of Warsaw and the head of the China-EU Programme at the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW).