Romania’s Plauru hamlet: a collateral victim of the Russian invasion

Over the past two months, Romania has been a victim of the Russian army’s clumsiness. Several Shahed drones have crashed in the hamlet of Plauru, on NATO territory. Local residents now live in const ant fear of future attacks.

November 15, 2023 -

Théodore Donguy

-

Articles and Commentary

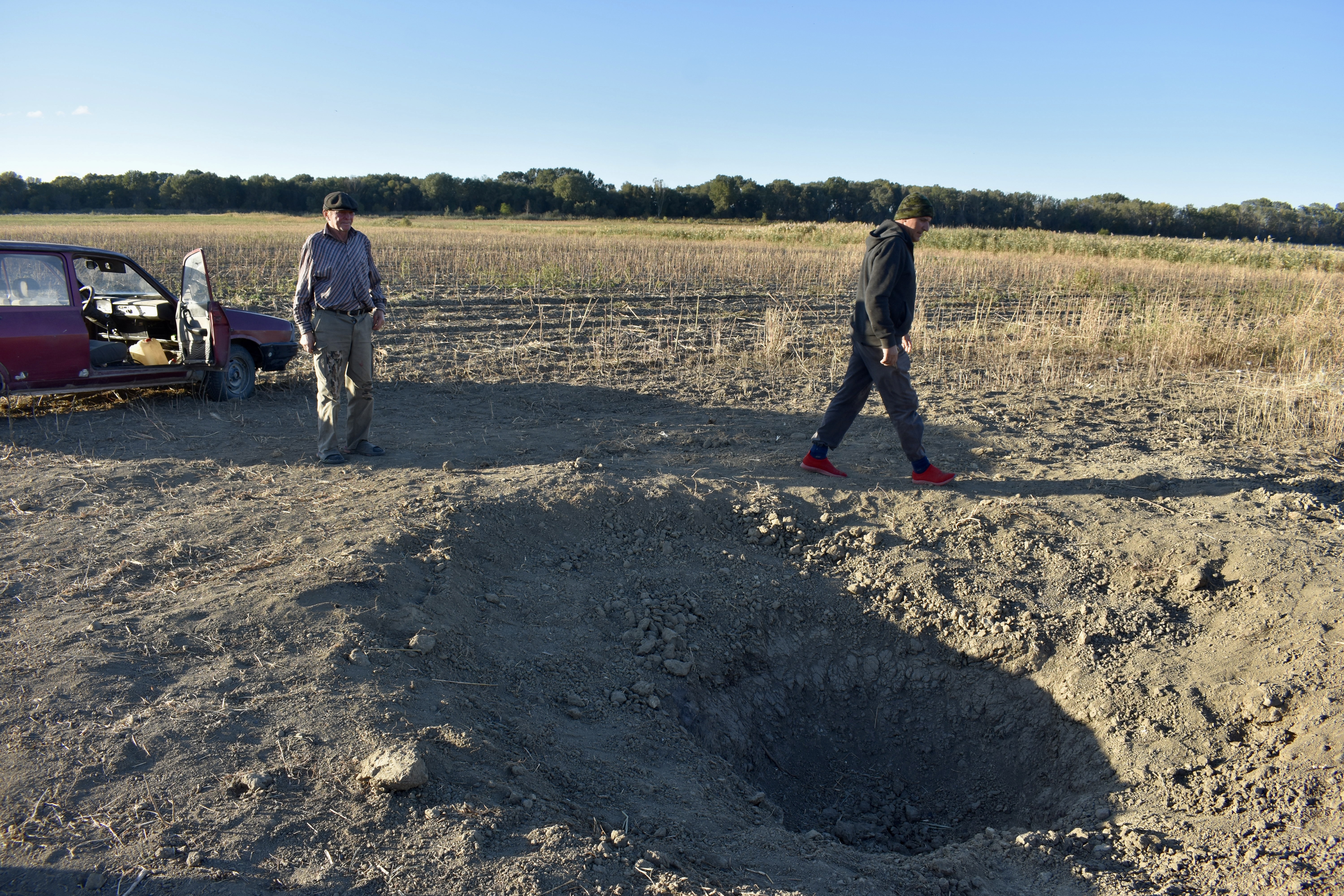

The residents of Plauru show us the new crater made by a drone in their village. ©Théodore Donguy

Since August 2023, the Tănase family has not been able to sleep peacefully. Russian drones bombarding the Ukrainian port of Izmail make the windows shake in their small house. However, Costel and Denisa Tănase are not Ukrainians. They are citizens of the European Union and NATO. They are farmers in the hamlet of Plauru, on the Romanian bank of the Danube, just 100 metres from the neighbouring Ukrainian port.

Since the start of the Russian strikes on Izmail’s infrastructure in August 2023, several Shahed drones loaded with 50 kilogrammes of explosives have detonated near Plauru. These kamikaze drones, in addition to posing a significant threat to Ukraine, now also endanger its neighbours. They explode just a few hundred metres from the Tănase family’s home. “Imagine for a moment if it had landed in our yard… We would have had nothing left,” Costel explains, looking at his wife with concern.

The twenty one residents of Plauru have had their lives disrupted for the past two months. The farmer angrily exclaims that “It’s already the fourth one now. You realise at any time it could have fallen right here!” With their 9,000 square metres of land and 12 cows, the Tănase family has everything it owns here in Plauru.

On October 13th, Costel Tănase discovered a new crater. It is not the first one he has visited. Early in the morning, after a night of bombings in Izmail, he easily locates the site of the explosion.This new one occurred at midnight. With his 1970s Dacia, he follows the trail of smoke escaping from the Romanian fields. When he arrives, the Romanian military has already passed through to remove the still-warm wreckage of the drone.

Four days after the explosion, the crater is still there, in the middle of a field of sunflowers. It is two metres deep, and the tire tracks from the Romanian military truck are still visible. All the evidence and debris were removed as quickly as possible. Since the beginning of the attacks, the military has maintained a constant presence in the region.

Here, due to the depth of the crater, there is no doubt for Costel that it was another Shahed targeting the port of Izmail. Besides the possibility of being directly hit by an attack, Costel is also afraid of the port facilities. “In the port, there’s maybe over 100,000 tons of ammonium nitrate. Imagine if there’s an attack and there’s some oil barrel there or something. It could be worse than Beirut, changing the course of the Danube,” he declared.

Costel, with his wife Denisa, shows us one of the strikes he had already filmed. ©Théodore Donguy

These strikes also impact the work of the residents of Plauru. Like Costel, some of them are fishermen on the Danube. The buzzing of the Shahed drones is similar to the sound of the engines of the area’s small fishing boats, and the risk of approaching the Ukrainian shore represents a significant danger. The fishermen are very concerned about the situation: “At night, we are not allowed to go out so as not to be mistaken for a drone by the Ukrainian anti-aircraft defence. They can confuse you at any moment.”

Romanian fishermen also voice concerns about the ecological impact of nearby ships. Dozens of vessels dock in the port of Izmail every day. Some of them release litres of diesel into the Danube, despite it having a highly developed ecosystem. Costel and the other fishermen have witnessed a significant decrease in the number of fish since the war began.

Gheorghe Puflea, another farmer from the village, also lives in fear now: “When the drones explode in Izmail, Ukraine, you don’t really feel them. But when it’s here in Romania, even my bed shakes at night.”

Izmail: Ukraine’s new strategic port

While this southern region of Odesa Oblast has remained relatively unscathed since the beginning of the conflict, it is now being targeted by the Russians. Izmail and its neighbouring port of Reni have indeed become strategic ports since Russia’s withdrawal from the Black Sea grain agreement. Active until July 17th 2023, this agreement maintained the free movement of Ukrainian agricultural products on the Black Sea. Concluded between Russia, the UN and Turkey, it facilitated the passage of over 1,000 ships loaded with foodstuffs from Ukrainian fields over the span of a year. This amounted to approximately 33 million tons of food, with 51 per cent of it corn and 27 per cent of it wheat.

In line with this expired agreement, Moscow no longer holds back and intensively bombards the infrastructure of the ports of Odesa, Chernomorski and Yuzhny. These were key points for exports. This strategic decision by the Kremlin aims to weaken the Ukrainian economy.

These exports make up between 11 and 12 per cent of Ukraine’s GDP and are mostly sent to developing countries. In a report on Ukrainian grain exports, the European Union Council highlighted the indirect impact of Russian bombardment on the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), the world’s largest humanitarian organisation. Around 70 per cent of the agricultural products exported from Ukraine went to countries like Ethiopia, Yemen, Sudan and Afghanistan.

These solidarity corridors, such as the one established through this Black Sea agreement, are crucial for containing the rise in grain prices. To ensure global food security and the functioning of its economy, Ukraine had to find an alternative. A key part of this new plan is made up of the ports of Izmail and Reni, located 200 kilometres south of Odesa on the border with Romania.

Izmail, a city of 70,000 inhabitants, is, with Reni, the new gateway for Ukraine’s economy. By rail, products are transported there and loaded onto large bulk-carrying ships that then head towards Africa and Asia.

Jovanovich, a resident of Plauru. Behind him, a section of the port of Izmail. ©Théodore Donguy

Izmail and Reni are cities that basically no one could have located before the start of the war. However, since July 2023, these two river ports have handled 25 per cent of Ukrainian grain exports. The infrastructure is rapidly expanding across the one hundred kilometres that separate Reni and Izmail. A dozen storage warehouses are now under construction. They represent strategic locations for Ukraine, and the Kremlin has clearly understood this reality. From Reni to the Black Sea, the last 165 kilometres of the Danube have been continuously bombarded since August by Russian artillery, primarily through the use of Shahed drones.

The Shahed-136, a crucial tool in Russia’s arsenal

The Shahed drones have become essential weapons for Russia. Of Iranian design, the Shahed is powered by a twin-blade propeller driven by a four-cylinder engine. The noise it produces closely resembles that described by the fishermen of Plauru.

With a range exceeding 2,000 kilometres, it is an effective means to target strategic cities far from the front lines, such as Izmail. With a length of 3.5 metres, the drone has 50 kilogrammes of explosives packed into its “nose”, firmly characterising it as a kamikaze drone. Each use of a Shahed is estimated to cost around 50,000 US dollars.

Whenever Moscow denies any involvement with Iran, it is important to remember that the same drones have been used in the civil war in Yemen since 2020. Iran offers support to the country’s Houthi rebels. In October, the Wall Street Journal revealed that Iran hoped to receive Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets in exchange for its involvement in the war in Ukraine. Since the beginning of this partnership with Iran, Russia has reportedly used nearly 2,000 Shahed-136 drones, according to an Airwars report. The first use dates back to September 13th 2022, in the Kharkiv region.

Ukraine is devoting significant resources to combat the Shahed drones. By the end of the summer, Kyiv submitted a report to the G7 to raise awareness about the origins of the Shahed drone. In this report, titled “Barrage Deaths: Report on Shahed-136/131”, five European companies, including a Polish subsidiary of a British multinational, are named as the original manufacturers of the identified components. Other components are said to be of Japanese, American or German origin. Iran allegedly arranges to have the parts first delivered to other countries before transporting them to Tehran. Then, from Iran, they are shipped to the port city of Makhachkala via the Caspian Sea.

“We feel like we’re not in NATO”

Faced with all this aggression and the extensive use of drones, the Romanian population feels that its government is not doing enough to defend them.

Romania, a NATO member, had initially rejected Ukrainian allegations that Russian drones had exploded on its territory. Out of fear of getting directly involved in the conflict, the Romanian government indeed failed to acknowledge the initial strikes. It took until the explosion on the night of September 5th for the Romanian defence minister to admit that the country had been attacked.

However, the residents of Plauru had already raised the alarm in August. A drone had already crashed a few kilometres from Daniela Tănase’s farm: “Nobody took us seriously, nobody came. We kept telling them, God forbid, what if one falls down on a house? They kept saying “no” to us. That is, until two of them fell here one night. One here, and another at the other side of the village.”

The Romanian government wants to avoid military involvement in the conflict. Nevertheless, Article 5 of NATO clearly states that an attack on one NATO member is an attack on all its Allies, and an immediate response must be initiated. Romanian residents do not feel like they are being defended by NATO.

In response to the situation, Costel said, “So what is NATO for? They should bring two, three anti-aircraft guns here. Once a drone crosses into our territory, BOOM, shoot it down. What’s the issue?”

Two anti-aircraft shelters have been built in Plauru.

At the moment, the Romanian authorities have established two shelters in the centre of Plauru. However, this is a measure that the residents have also criticised. Without proper reception, they cannot receive alerts on their phones, rendering the shelters useless.

One of the shelters behind a “Caution, Children” sign in Plauru. ©Théodore Donguy

Jiovanovich, 68, lives just a few metres from the shelter. He would like to be able to use it but explains the key problem: “We don’t receive bomb alerts. We have no network here. Even to make a phone call, we have to go up to our attic or on the roof of the barn. It’s only after the explosion that they tell you, “Watch out, something is falling from the sky!””

All the residents of the hamlet now live in fear. The fear of one day seeing one of these drones land on their own house. They do not feel supported enough, or defended enough by their army, even though it is part of NATO. In any case, their whole lives are here, in Plauru.

Théodore Donguy is a French freelance journalist covering migration and international relations. He studied journalism at ESJ Lille and political science at the University of Lille. He has been published in European outlets including VoxEurope, Paris Match, Hampshire Chronicle and France 24.

Please support New Eastern Europe's crowdfunding campaign. Donate by clicking on the button below.