A post-mortem monument

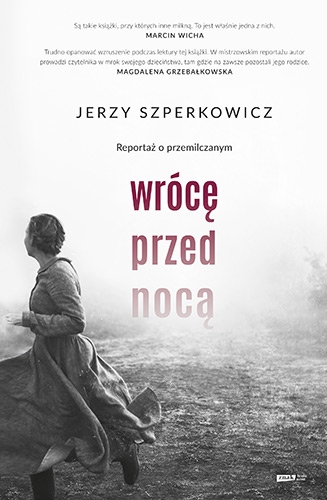

A review of Wrócę przed nocą. Reportaż o przemilczanym (I will come back before dusk. A reportage on the unspoken) By: Jerzy Szperkowicz. Publisher: Wydawnictwo Znak, Kraków, Poland, 2021.

September 12, 2021 -

Paulina Małochleb

-

Books and ReviewsIssue 5 2021Magazine

Jerzy Szperkowicz is a famous Polish reporter from the communist period and a Russia specialist who spent 18 years, from 1956 to 1974, as a correspondent for the Polish daily Życie Warszawy in Moscow. After many years of silence, he has now made a comeback in the Polish publishing scene. He has returned with a story, written in his old age and faced with terminal illness. It is his final, extremely personal, narrative of his childhood and the murder of his parents.

Haunted by guilt

I will come back before dusk (Wrócę przed nocą) – the title of Szperkowicz’s book comes from the words his mother uttered before she had left their home in today’s Belarus one early morning in 1943. She headed to a nearby village where she had left some of their belongings at an acquaintance’s place. This scene of departure bears many warnings, which are easy to read today but were not so clear at the time when the events were unfolding. Thus, Jerzy, who as a ten-year-old, could only see the silhouette of his mother as she was disappearing on the horizon, continues to be haunted with guilt for the rest of his life. He did not wake up his father to turn his mother back. As a result, only three months after childbirth, she set on a journey to fetch some baby clothes and some money to pay relatives who had offered them shelter after they escaped from their estate.

Today, we know that any journey in this area in 1943 was doomed to end tragically. Just as much as any attempt to fetch one’s belongings from the people who had promised to protect them. Thus, the death of Jerzy’s mother was followed, one month later, by his father’s murder. He was dragged out of the house by guerrilla fighters and shot to death soon after, without any trace. This left the three young Szperkowiczes (Jerzy and his two siblings) homeless and wandering, which came to an end only after the war when they relocated to Poland together with thousands of other resettlers from the Soviet Union.

Szperkowicz’s story is not a simple, emotional confession. Just the opposite. The events are spread out, dramatised and put into order. Through language, or by silencing some parts out, he builds symmetry, or omits it. Consequently, the reader learns about the author’s childhood, the early stages of the war and the changes that took place on the frontline. The story about the army marches is completed with a description of the departure of his mother.

Language and silence

Later on the story moves to the time when Szperkowicz is no longer an orphan. He returns to his childhood land as an old man. There he seeks the truth about his mother’s death. And again applies the dialectic of language and silence to depict the investigation into his father’s death. As part of it, he meets with many witnesses. However, their testimonies only allow him to reconstruct his mother’s last days. And the silence remains when it comes to his father’s last moments. Clearly, nobody has any knowledge about it. Sadly, the tragic fate of his parents was quite representative and typical for what took place during the war in the “Bloodlands”, to use Timothy Snyder’s phrase.

His mother died after having been tormented by neighbours who were led by a local self-proclaimed guerrilla fighter. He was an ordinary criminal who managed to spread fear among the community to the point that nobody had the courage to offer a cup of water to their friend and neighbour who had given birth just weeks beforehand. Beaten and raped, shaved and tortured and accused of spying (which ostensibly justified the violence and the interrogation) she was agonising for several days in a village located just under 20 kilometres away from where the family was based at the time.

Szperkowicz’s father disappeared overnight. Nobody knew who had taken him or why. The only thing certain was that it was not the work of the German army. With them Szperkowicz’s father had more success; he managed to hide Jews at his estate where he also provided refuge to Polish and Belarusian guerrilla fighters. He provided hospitality, even at his life’s risk. The last time Szperkowicz applies the contrast between language and silence is when he analyses his own investigation, which also undergoes a transformation throughout the book. While he first focuses on the past, or the mystery of his father’s sudden yet ordinary death, he later refuses to follow every trace.

Some lines cannot be crossed

Szperkowicz spent many years visiting the area of his family’s estate, penetrating the Belarusian-Lithuanian borderland. He visited houses, met with former servants and neighbours, as well as their children and grandchildren. He talked to local priests, visited parish churches (Catholic and Orthodox) in search for documents. And yet he stepped back from his search when one of his interlocutors suggested he should check the NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) archives. Anything can be found there. Despite years spent searching and maintaining a fragile balance between nostalgia and personal grief and a desire to find the truth, Szperkowicz refuses to take this path. He is convinced that some lines cannot be crossed, even for the sake of truth.

Yet his report and a very personal story can be uncomfortable reading. Not only is the reader faced with a story about violence, but various political issues also play a role in the book. First there is the class issue. The Szperkowicz family belonged to the group of Polish Catholic landowners. In the interwar period this meant being part of a privileged group; and even though they were affected by the outclassing, their financial position was still much better than Belarusian peasants who lived in neighbouring villages. Thus, the murder of his parents was, to a great extent, an act of class revenge and religious hatred, which was easier to perform at the time of war when nobody would undertake an investigation.

Politics, ethnicity and memory

Szperkowicz does not dwell on this issue in a sentimental way, unlike the Polish narrative on the “lost Borderlands”. His book offers no idealisation of the past, it includes no affectionate memories of the lost estate and has no nostalgia for the apparent harmony between various ethnic and religious groups. Conversely, Szperkowicz is well-aware of what Polish politicians did in these areas during the interwar period. His own family (both grandparents and parents) drew conclusions from the subsequent protests and the anti-feudal rebellions of the Haydamaks. In order not to lose the estate in arson, they put many efforts into establishing good relations with their neighbours. They showed them that they cared about them and were interested in their lives, instead of displaying their wealth. Second, there were ethnic issues. The Szperkowiczes were victims of their Belarusian neighbours. Clearly, the family’s efforts to maintain good neighbourly relations did not bear fruit at a time when both Soviet guerrillas and local Belarusian forces were easily instigating others against Poles. Both symbolic and collective responsibilities were in place.

The events intensified as the sense of threat increased. The Szperkowicz family, warned by a neighbour, knew that they had to leave their collapsing estate behind as Belarusian nationalists were only waiting to take over the mansion. This kind of looting was tolerated by the Germans. Evidently, it was getting riskier and they could feel the end drawing near. The family escaped from the mansion – just a few months before his parents were murdered.

Third, was the issue of memory. This is probably the most fragile topic discussed in the book. Undoubtedly, Szperkowicz’s work is revolutionary in this regard. It goes against the rhetoric of the Great Patriotic War and the legend of the Belarusian guerrilla fight. It is a legend that was cherished when Belarus was part of the Soviet Union and continues to this day. The myth of the heroic fight with the Nazis fuelled Belarusian patriotism many years ago, while now it is becoming a foundation for the new Belarusian opposition. It remains unquestioned and its unifying energy is often exploited. It is needed when references are made to wartime efforts, the victims and their sacrifices, and when women’s role in the fight is emphasised. The myth of this war is both creative and modern.

Safeguarded memory

Szperkowicz, however, offers us a story that is both personal and bloody. He shows that under the guise of guerrilla warfare, local looters and bandits committed crimes not only against those whom they considered class or ethnic enemies, but against those who were like them. Thus, they used guerrilla tactics as a pretext to blackmail already robbed peasants, raped women and orphaned children. By demanding that they are held accountable and that individual crimes are included in local memory, Szperkowicz suggests that no country can carry on properly as long as it tolerates the destruction and silencing of individual experiences. When searching for traces of his mother, he came across a wall of silence – one built out of fear of the new system and the sealed lips of ordinary people.

This book is not a revolutionary or political piece of writing. Nor it is a work based on sentiments. Szperkowicz wrote it to defend his individual truth with full awareness that his story can be manipulated and used as a demand for punishment for inflicted harms. This, however, was not his goal. For this reason, he was very precise in building his story. As a result, I will come back before dusk can be seen as a kind of tomb – a monument that Szperkowicz has built to commemorate the memory of his parents whose burial site is still unknown. Thereby, he has safeguarded their memory in the only way he could. And he did it beautifully.

Translated by Iwona Reichardt

Paulina Małochleb is a literary critic, researcher and lecturer. She publishes in, among others, Polityka, Krytyka Polityczna, Przekrój. She is the laureate of the Prime Minister’s Scholarship for Young Researchers, and a “Młoda Polska” scholarship holder from the National Centre of Culture. She is the author of the book Rewriting history. The January Uprising in the Polish novel from the cultural memory’s perspective and blogs at www.ksiazkinaostro.pl.