The thieves in law

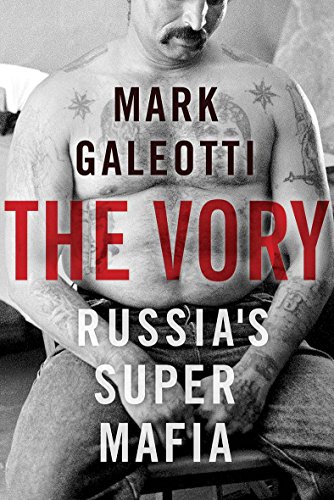

A review of The Vory: Russia’s Super Mafia. By: Mark Galeotti. Publisher: Yale University Press, New Haven/London, 2018.

April 11, 2021 -

Lasha Bregvadze

-

Books and ReviewsIssue 3 2021Magazine

The first time I picked up Mark Galeotti’s book, The Vory, I was overwhelmed and my heart started beating a little faster. Not many books have been written on this subject. The issue is very specific and a bit complicated to formulate and analyse. As far as we know, no representative of the former post-Soviet countries has even attempted to publish something on the subject, neither literary nor an in depth academic analysis. Whereas this topic is delicate, some people are more concerned about personal issues while others just try to forget about it altogether.

Given the complicated nature of this topic (the vory are a type of criminal organisation which cannot be found anywhere else outside post-Soviet countries), the titanic work carried out by Mark Galeotti, an Honorary Professor at the University of London’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies, is quite impressive. The book is written very lucidly and it does a good job of describing certain events, starting with tsarist Russia and ending with today’s realities.

Criminal class

Galeotti introduces all the vicious practices that have developed since the time of the Russian Empire, and later within the Soviet Russian Empire when it reached its peak. After the perestroika period and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the vory had been transformed into a much stronger and more dangerous organisation, becoming a threat to the country itself (here I mean Russia and a few young republics where this subculture had deeply penetrated into society), and the rest of the world. As the author describes, after these criminal gangs became stronger they started robbing and oppressing citizens (mostly during the so-called “wild 90s”) and consuming the country’s main resources they also drew their attention to European and American cities. Galeotti tried to describe the representatives of the criminal subculture formed in the young republics and their structures, although it is easy to see that this topic is not well reviewed in certain places (for example, in Chechnya and Georgia). For readers not well aware of these issues, they will gain a lot of interesting information after reading this book.

As someone who grew up in this environment, and participated in the reforms that took place in the Georgian penitentiary system after the 2003 “Rose Revolution”, I had quite a close relationship with criminals of all levels, including the so-called vory, translated as “thieves in law”. Starting with the historical part of the book, the author depicted the story of Benyia Zubriak. By describing his life, Galeotti tried to show the dark side that is common with this subculture. It would have been better to delve deeper into the history of the origin of the vory. It is noteworthy that the first so-called authorities appeared in Odesa during tsarist Russia. They were named “fartovyy” (фартовый) which means “lucky”. The people with this title had special respect in the criminal world. The term vory or “Ramkiani” was introduced later on. After the formation of the Soviet republics, there was a need to control and contain the criminal sphere. As it is with the economy, demand always creates a need to produce. In this case, high-ranking officials of the NKVD and other security services encouraged the emergence of these types of criminals, who became a new and untouchable caste.

Unfortunately, two of my fellow-countrymen, Ioseb Jughashvili (Jospeh Stalin) and Lavrenti Beria, facilitated their formation. The rules of conduct were created for those who followed a thieving tradition. It is ridiculous that this code puts law enforcements in an advantageous position and makes it easier for them to control the thieves (for example, it was strictly forbidden to make any kind of confession or write a complaint). However, after the Second World War, this set was also transformed and led to a major confrontation between two powerful groups. The “righteous thieves” who, in their view, lived a proper life, confronted those who were well-disposed towards the prison administration, on the path to correction, or who participated in the war (the so-called “suki”). Of course, this confrontation was won by the latter group, with the support of security services and law enforcement agencies.

This fact is decisive in the vicious transformation that this sequence finally received. It has become common practice between the prison administration and criminals to exchange and co-operate in certain activities. Eventually, after many years, this relationship would turn into a criminal formation that does not shun the use of special black cars with passes, taking advantage of prison guards, participating in public tenders, and receiving funding for large state projects.

Georgian Robin Hood

It would have been better, in my view, if the subcultures in Georgia and Chechnya had been studied in greater detail, since the emergence of a criminal mentality dates back to the tsarist period. The outlaws at the time were patriots who loved their countries and fought against Russian tsarism, such as the hero of Chechenia, Imam Shamil, who was actively fighting against the Russians and was declared an outlaw. Georgian outlaws “Abrages” (outlaw “Abragi” or a man who goes to the forest and his way of life was robbery), Khareba Djibuti and Gogia Kenkishvili, are still very popular figures in Georgia. Also it is noteworthy to mention Arsena Marabdeli, who actually existed in the 19th century and was distinguished by the fact that he mugged the rich and gave to the poor – a sort of Georgian Robin Hood. Similarly, the book Data Tutashkhia, which was written by the famous Georgian writer Chabua Amirejibi, is considered one of the most significant stories in Georgian literature. This literary work accurately expresses the problems that plagued the Georgian people at that time and it describes the real situation of many Georgians.

Coming back to Galeotti’s book, I would like to refer to the chapter titled “Georgia” which describes the phenomenon of the thieves’ understanding in Georgia. Galeotti describes the odious Jaba Ioseliani, who started his life like a vory and in the 1990s created one of the most powerful and ruthless gangs in Georgia, the Mkhedrioni. This criminal group, under the shield of “patriotism”, murdered hundreds of people during the civil war. Ioseliani managed to reach a high position in government. It is interesting that this issue has not been studied as scrupulously as it should have been, because Mkhedrioni was created by him. In fact, it was a “sectarian” movement in the thieving world with similar customs and rules of conduct. In the case of the murder of two prominent thieves in law for that period (Arsen Mikeladze and Anzor Aghayani), there were suspicions about the involvement of Jaba Ioseliani. This led to action against Ioseliani and his gang (they lost their status and privileges).

Galeotti also refers to the influential and powerful person Anzor Kvantrishvili, who was nicknamed the “golden brother” (золотой фраер) as a sign of respect and attention by the vory; he was actually a bridge between the criminals and the government. He created a charity fund which in reality was a huge money laundering organisation. Kvantrishvili was in close contact with prominent singers like Ioseb Kabzon and Alla Pugacheva. In fact, he kept close ties with influential and successful people from various areas of life. In all the cases where the interests of representatives of the state or the law enforcement system were crossed with criminals, the “Golden Brother” was involved.

Quest for more

The fact that there was such a large percentage of Georgian “thieves in law” in the Soviet Union was because they could keep balance among the criminals from other nations, such as those from other Caucasus republics including Chechens, Armenians and Azerbaijanis. Other Caucasian nations, in fact, considered Georgian criminals to be an equal, and often authoritative due to their strong character. It was much easier to communicate with a Georgian because it was understood he would never break his word, something that is very important in Caucasian culture.

As for the chapter on Chechnya, it is worth mentioning that perhaps more deliberation was needed to describe the life of someone like Imam Shamil, who for many years opposed Russian tsarism, uniting Dagestan, Cherkessia and Chechnya into a united Islamic Imamate. Despite having patriotic goals, he was considered an outlaw for many years. It is sad to mention that, currently, we have such an odious figure in Chechnya as Ramzan Kadyrov. What is happening in Chechnya today is that the nation is divided into two groups: the patriots and those serving Russia for their survival.

Galeotti’s book comes across as very interesting and informative. I would emphasise that the topic of the vory requires a more in-depth examination. This area is quite specific and it is necessary to expose all the vicious practices and developments that happen between the vory and post-Soviet law enforcement agencies. In many cases, this relationship has grown into co-operation and mutual benefit.

Criminals, for a long time, have been taking instructions or interfering in democratic processes such as elections. They assist law enforcement agencies in maintaining power and in return, the regime provides guarantees of inviolability and financial well-being. The fact is that this sequence, which was still in its infancy during the tsarist period, was based on the cornerstone of protest and disobedience of the system. Unfortunately, the strong (or rather the influential) always take advantage of a relatively weak opponent.

Lasha Bregvadze is an independent expert who works with the Georgian Strategic Analysis Center.