Propaganda, a “Cursed Region” and the Yanukovych disease: a review of Olena Stiazhkina’s Ukraine, War, Love: A Donetsk Diary

The ongoing war in Ukraine now finds itself fighting for the attention of the global media. Thankfully, Ukrainians are managing to keep their plight alive in a myriad of ways. In her new book, Olena Stiazhkina describes her own experiences of the Russian invasion.

February 2, 2024 -

Nicole Yurcaba

-

Books and Reviews

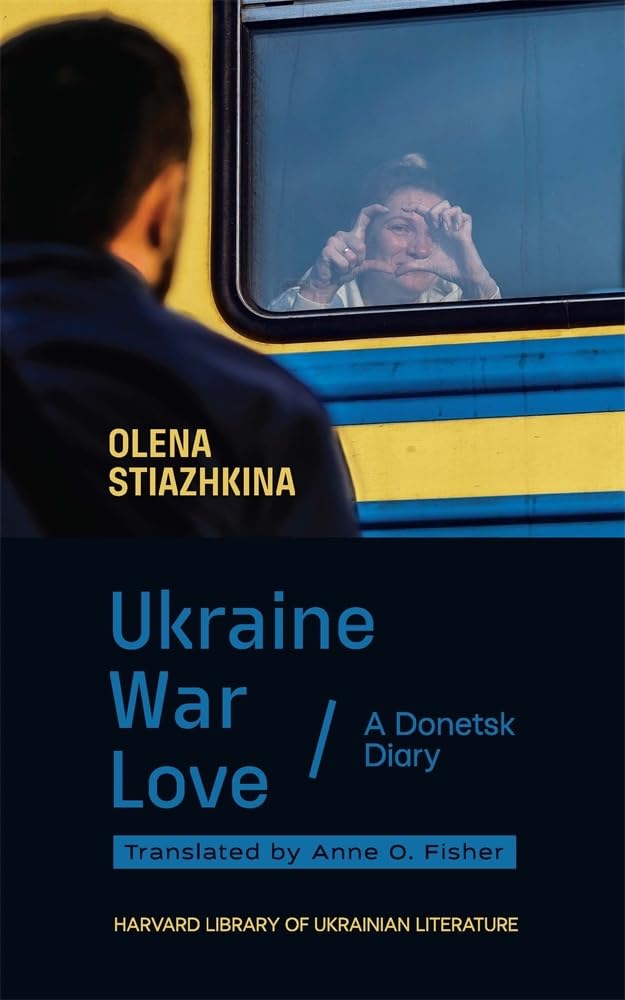

Cover of Ukraine, War, Love: A Donetsk Diary. Source: Amazon.com

“Not seeing Ukraine is a disease. Ask Viktor Yanukovych what that disease does to you,” writes Ukrainian author Olena Stiazhkina in one of the opening entries of Ukraine, War, Love: A Donetsk Diary, which appears in translation thanks to the work of the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. Unfortunately, “not seeing Ukraine” is becoming a global issue, especially as more and more disinformation about Kyiv’s counteroffensive and global war-weariness threaten further aid to Ukraine from the United States. As Stiazhkina points out, many politicians around the globe, and particularly in the United States Congress, should ask Yanukovych what that “disease” does to an individual, but very few will take the time to do so. Thus, Stiazhkina’s latest contribution to the conversation about Ukraine’s right to sovereignty is an imperative read for those civilians educating themselves about the historical context of the war in Ukraine so that they, in turn, may communicate their support for Ukraine to their politicians.

Deeply personal and at times unnerving, Stiazhkina’s diary entries depict an eastern Ukraine ravaged by Russian propaganda. The entries depict the initial Maidan and post-Maidan days during which – when one was afraid or “lost heart” – one should “sing the national anthem” because it was “really good for driving out devils”. These entries capture a rejuvenated and fresh Ukrainian patriotism that swept many areas of Ukraine, not only when Yanukovych threatened to further tie Ukraine to Moscow but also when the war in the Donbas and the annexation of Crimea began. Stiazhkina’s language is direct yet emotional, especially in passages about Vladimir Putin’s desire for war and how “Conquering Ukraine is something he can probably do.” Despite this, the Russian leader “can’t kill Ukraine” because to kill Ukraine “he has to kill me, russkaya, a Russian. And he has to kill other Russians too.” Thus, Stiazhkina enters the emotional, even intellectual, territory of identity and language politics that Putin warped to stoke the flames of discontent and propaganda not only in Russia, but also in areas like Donetsk. Stiazhkina also boldly, yet adeptly, tackles the stigma with which those from Ukraine’s eastern regions initially lived during the war’s early days. She refers to the eastern regions as “this cursed region” and acknowledges that its inhabitants will “bear the responsibility for everything. Collectively, as is the custom”.

Other passages carefully refute the propaganda which mislabeled Russia’s invasion as a “civil war”. In these passages, Stiazhkina quite effectively correlates the misnomer “civil war” to American history. She acknowledges that there are people in Ukraine “who want to live in Russia”, and she initially relates this to the 18th-century United States – the time period of the American Revolutionary War in which there were people “sincerely devoted to the English crown”. She also clearly defines what the term “civil war” actually means in the context of Russia’s aggression in Ukraine’s eastern regions, and again Stiazhkina effectively utilizes a reference to America’s Civil War, which occurred between 1861 and 1865: “Civil war is when some people believe the United States of the future won’t have slavery, while other people are sure it will.” Presenting the two expansive American historical periods might effectively communicate to western readers, and particularly American ones, how Ukraine’s struggle for independence, democracy and sovereignty echoes America’s external and internal struggles. She then stresses a disturbing image to refute the accusations that the conflict between Russia and Ukraine is merely a civil war: “But, when somebody wants to live in another country, when somebody gets physically sick when they hear the word “Ukraine”, when the sight of blue and yellow burns somebody’s eyes like acid, then, for goodness’ sake, how is that a civil war?” These words were written during a time in which much of the world had yet to hear about Russia’s everyday incursions into Ukraine. However, for current readers who have remained abreast of the situation in the country since the February 2022 full-scale invasion, the images will bear a striking resemblance to much of the Russian reaction, misinformation and disbelief about Moscow’s actions in 2022.

Stiazhkina manages, too, to give voice to the human toll of the war in her entries. She focuses not necessarily on body counts, though she does mention or allude to them. Instead, she centres the focus on the individual, emotional toll individuals pay during wartime. She writes that one learns to “not think of everything through war”, that “the hardest thing” is that there is “no past. No future. There’s only what there is now.” At another point in the diary, she jarringly relies on the metaphor of a raped woman to describe Donetsk: “Yesterday, she was carefree and loved. Beautiful, especially in the morning. And then the thing that happened… happened.” As the book continues, the emotional toll paid transcends from the individual to the collective and the national. Rather than concentrating on the regional cost of capitulating to Russian aggression, Stiazhkina appeals to the inherent, national Ukrainian resilience which has shocked and awed the world since February 24th 2022:

Yesterday, I thought about this: if she, my little girl, my Ukraine, ceases to be—

what will change for me personally?

Nothing.

If she dies under the new Russian boot, if she dies from the old Hetman

betrayal, if she’s smothered by manicured hands of her West-European mourners,

nothing will change for me. I won’t stop loving her.

However, one cannot overlook the eerie immediacy of Ukraine, War, Love: A Donetsk Diary. Despite its now historical setting, its carefully curated reflections resonate with today’s Ukraine, where eastern village after eastern village is pummelled by Russian missiles and drones and the internal displacement of nearly 3.7 million people causes multiple humanitarian crises within and throughout Ukraine. Ukraine, War, Love: A Donetsk Diary, too, reminds readers about Ukraine’s historical struggle for independence and Russia’s centuries-old agenda to control the region regardless of Kyiv’s sovereign borders. More significantly, nonetheless, the book serves as a time capsule, documenting the human experience of individuals fighting for survival at a time when the eyes of the world are shifting elsewhere.

Ukraine, War, Love: A Donetsk Diary by Olena Stiazhkina. Harvard University Press 2024.

Nicole Yurcaba is a Ukrainian American of Hutsul/Lemko origin. A poet and essayist, her poems and reviews have appeared in Appalachian Heritage, Atlanta Review, Seneca Review, New Eastern Europe, and Ukraine’s Euromaidan Press. Nicole holds an MFA in Writing from Lindenwood University, teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University, and is Humanities faculty at Blue Ridge Community and Technical College in the United States. She also serves as a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and Southern Review of Books.

Please support New Eastern Europe's crowdfunding campaign. Donate by clicking on the button below.