The need for decolonisation

Decolonisation in Eastern Europe is different from other, especially western, decolonisation experiences. There is no one algorithm that would determine in which way a society or country would pursue the process of decolonisation. In Ukraine’s case, but also that of the whole region of Eastern Europe, the initial stage of decolonisation showed a return to the alternative centre – the West.

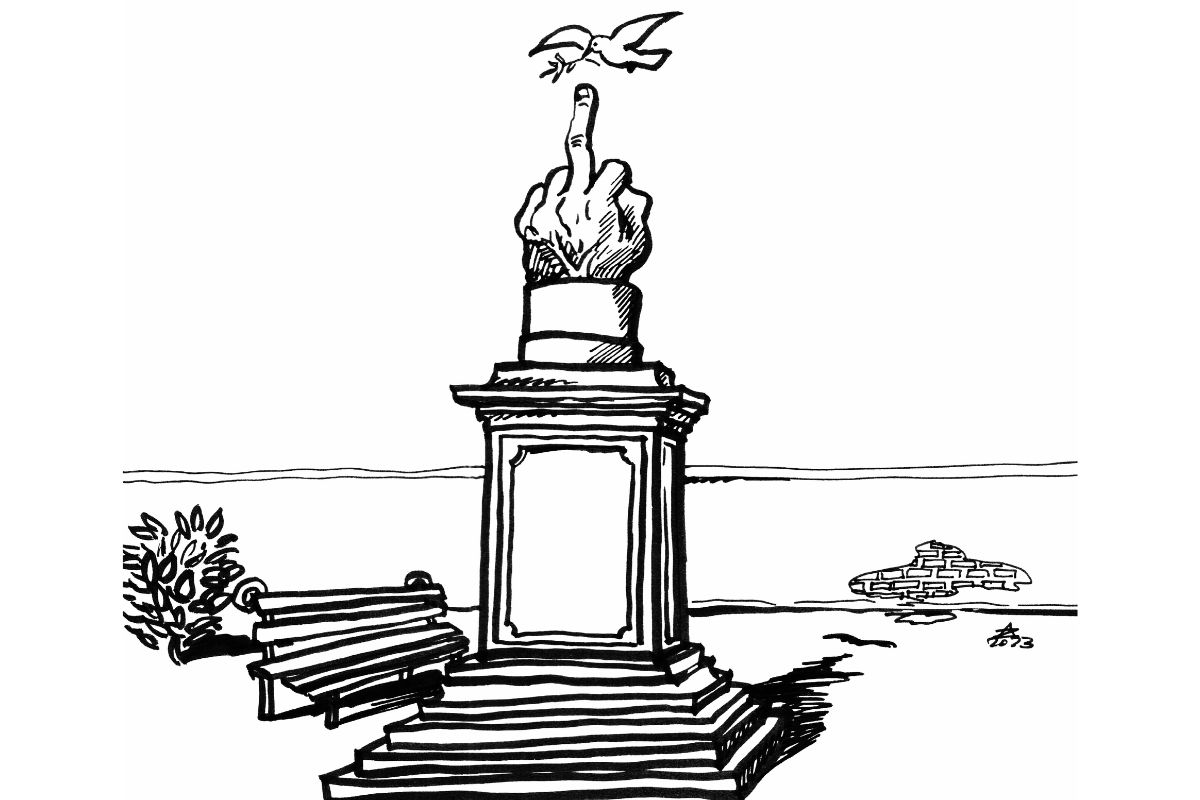

“We will regain Odesa and everything will be back in place! Monuments will get removed and street names changed,” reads a comment on the website of Russia’s state-owned information agency Ria Novosti. It was placed under an article describing the removal of the Catharine the Great monument in Odesa. In a nutshell, these two sentences present the discourse that has developed in Eastern Europe around the topic of decolonisation.

November 16, 2023 -

Anton Saifullayeu

-

History and MemoryIssue 6 2023Magazine

In theory, decolonisation, or a decolonisation shift, refers to a process of denaturalisation of existing (i.e. colonial) order of knowledge. As such, this process eventually leads to a change in the way a society thinks about itself, the world, the past and the future.

In today’s Ukraine the process of decolonisation has been accelerated by the changes that have been introduced to the country’s legislation, but traces of it can also be spotted in other areas of the public sphere as well as the personal choices that are made by everyday people. This includes: laws on de-communisation, de-Russification and decolonisation of place names which we have been seeing since the beginning of the full-scale invasion as well as eliminating Soviet elements from the narrative surrounding the Second World War. Sociological surveys also show that the number of people using Russian in everyday life in Ukraine has decreased by ten per cent.

Anti-colonial war

Despite all this, it still is too early to firmly and decisively say that Ukraine has made a complete and irreversible decolonisation turn. For this to happen we would first need to see an ideological consolidation of the ruling populist political elite, local authorities, but also public intellectuals, bloggers, media workers and Ukrainian researchers abroad. A potential decolonisation has everything it needs to start as a social and political process.

As tragic as it sounds, Russia’s aggressive imperialism and the full-scale invasion that the Kremlin started in Ukraine on February 24th 2022 have proved to have a significant impact on the decolonisation process in Ukraine. Specifically, we can say that the anti-colonial language in the country’s legislation and official rhetoric of the authorities are both a result of the military activities and the atrocities committed by the Russian army against the Ukrainian population and on Ukraine’s territory.

However, the dynamics and impulsiveness of these processes explain why the decolonisation is dependent on the war and its outcomes. Namely, should Ukraine win the war, we will have a chance to see a full-scale decolonisation with a large social support. Conversely, if the outcome of the war is not to Ukraine’s advantage, there is a risk that some parts of the society will turn back on this decolonisation processes which have already begun.

Overall, decolonisation in Ukraine takes the form of erasing colonial, Russian and Soviet heritage as well as the impact it has had on Ukrainian national identity. This means that the society that is experiencing an anti-colonial war and fighting for its freedom understands the decolonisation process. This is in sharp contrast to the Kremlin’s belligerent rhetoric about Ukraine’s “lack of existence”. Thus, this quite impulsive nature of the decolonisation process which is currently underway in Ukraine could have an impact on its outcome. This is especially true in the most “sensitive” regions in the country – the east and the south. The rhetoric of the state political and military leadership who stress the full liberation of Ukrainian territories from Russian occupiers and return to the pre-2014 borders as well as the complete removal of all signs of Russian and Soviet heritage can, for some people there, be very sensitive.

Overall, Russia’s full-scale invasion in Ukraine has brought deep consequences not only for Ukraine but also the entire post-Soviet space as well as the framework of our academic and analytical knowledge about this region. We can thus daresay that starting with February 24th 2022 the post-Soviet period has come to an end and the perception of Russia as an “older brother” – an image which not that long ago was still present in some post-Soviet states – is now a part of history. The new generation in the region no longer believes in the old myths about the Great Patriotic War nor does it become allured by the fictional stories about the good life in the Soviet Union. Significantly, this generational change is taking place at a time when many people worldwide are rethinking their admiration for the “great Russian culture”. These changes, while in place, are nonetheless as Russian propagandists like to say, not so “straightforward and free from ambiguity”.

Decolonisation of post-Soviet studies

Russian colonialism is probably one of the latest discoveries in the field of post-Soviet studies. Indeed, until recently and for too long western academic discourse about Eastern Europe was under the strong influence of the old colonial clichés which stressed Russia’s civilisational and ethnocultural importance for the development of the region and its states. Thus it is only since last year have the earlier believers in the so-called area studies which, in the realm of international relations, focus on countries such as Belarus, Georgia, Ukraine but do it through the prism of the “greater” Russia, have started to call for the need to decolonise Russian studies and the overall knowledge about the post-Soviet space.

Seemingly, it had to take such a horrendous act as the full-scale war in Ukraine for concepts such as colonialism, orientalisation or decolonisation to no longer be perceived as the theoretical whims used by some scholars engaged in the discourse about Russia. Arguably, even the term “full-scale war” could be seen as a euphemism which is used to describe the gravity of the current situation as well as the need for a change in perception about Russia, its policies, but also in the perception of Ukraine and its agency. All said, we need to remember that in the West many academics saw the outbreak of the war between Russia and Ukraine in 2014 as a political event. In their view, the annexation of Crimea but also the war in Donbas were more elements of geopolitics and belonging to the analyses of Russia’s needs than a reflection of Kremlin’s colonial policies.

This takes us to one of the most problematic issues of the decolonisation process which has a meaning not only for Ukraine, but also for the region as a whole. It could be captured in a question as how can the academic knowledge about Russia and the post-Soviet space be liberated from the existing framework, also of the global decolonisation discourse, which reflected and brought on a simplified perception about this region. Evidently, the changes that have taken place in this regard since 2022 can be interpreted as reactive. One may even have an impression that someone wanted to quickly fix the mistakes of the past. Yet, such an observation also suggests that there has been no overall, complete, plan as how to construct knowledge about the countries that were or have been under Russia’s colonial influence. Nor how to change thinking about Russia’s civilisational imperialism.

Equally problematic is the overall low level of knowledge about Russia in the area of humanities worldwide, which can be explained by a few factors. First, the interest of today’s researchers into decolonisation processes skews towards the so-called Global South. This area has become a certain mainstream of academic investigation, especially among scholars specialising in post-colonial studies, inequality research, migration studies and racism research overall. Paradoxically, the post-Soviet space, which also desperately needs a post-colonial approach, has been excluded from the global community of post-colonial studies. This is most likely the result of the long-lasting perception of Russia (or earlier the USSR) which is presented and seen as the liberating actor in the Global South. The narrative about the anti-colonial policies of the Soviet Union and its fight against imperialism and the creation of a paradise on earth have been widely promoted in Africa, South America and Asia since the 1950s. They also seem to have completely blinded left-wing thinkers both in many Western European countries and their former colonies on other continents. That is why, in the view of the post-colonial states, which were victims to the colonial policies of the European powers, there has always been one main coloniser – the West. Consequently, any arguments about Ukraine’s decolonisation are met there with the lack of understanding. The same goes with the arguments that the language used in colonial discourse in other parts of the world does not apply to Ukraine’s case. Instead, the support that Ukraine has been receiving from the US and EU is interpreted as evidence of western colonisation of Eastern Europe. Therefore, arguments that Ukraine has been fighting for its freedom in a neo-colonial war, which was started by Russia, are so difficult to comprehend.

Russia’s rhetoric and policies

Vladimir Putin’s regime is effectively using the old Soviet anti-colonial narrative in its foreign policy. In Africa, where Russia’s policies are clearly driven by economic interests, but also in Latin American, messages about stopping the West or weakening it by means of the war with Ukraine, are not only used as propaganda and diplomatic tools, but also serve the rhetoric that is easily absorbed by local experts and intellectuals.

Since 1991 Russia has been fostering a post-imperial identity which exploits the feeling of nostalgia for the “great” past and former prosperity. It was already during the presidency of Boris Yeltsin, which did not last long, that the concepts of Russkiy Mir, Eurasianism, or national bolshevism entered public discourse. Since then, social, intellectual and political reactionisms, fuelled by Soviet nostalgia, have become a permanent component of the new Russian identity.

However, the most important factor was the lack of a “unifying” concept which would play the role that Maxism-Leninism had during the Soviet times or autocracy (самодержавие) did in tsarist Russia. Things changed when Putin came to power, who found the base for his new regime in some extreme ideologies. As a result, the “uniting” idea promoted by the Kremlin today is a mixture of imperial and colonial sentiments which are composed of both the idea of Russkiy Mir and Soviet nostalgia. The most illustrative embodiments of this ideology are the celebrations of the Unity Day, which commemorates Russia’s liberation from the Polish domination in the 17th century, and the Victory Day, which is held on May 9th and marks the Soviet victory over Nazism and fascism. These nostalgic reactions have created a situation where Russians no longer think about their identity in national terms and instead opt for values that have been nurtured by the oligarchic economy and Darwinistic social reality.

There also seems to be little hope in the Russian opposition, which lost in its fight against Putin in 2012. The actions and writings of this so-called liberal group unfortunately shows that in Russia the process of de-imperialisation has never had a chance to succeed. Not much has changed in this regards even after February 2022 when the image of Russia as a coloniser became internationally more common, but which did not get rooted in Russian public discourse, including that of the liberals. Instead, there are still attempts to revive the rhetoric about “brotherly nations” and “common past and traditions”. It had to take the Ukrainian discourse that has pushed the Russian intellectual elite to pursue a more structural thinking about its current state of mind in this regards and stop using such excuses as “this is all Putin and his propaganda’s fault”.

Sadly, and surprisingly, in a country as large as Russia there are no intellectual, nor political forces that could change this paradigm and bring an end to the colonial thinking, just as it was the case in many Western European states. Possibly some change will come as a result of Russia’s external decolonisation which we could see as having partially started since 2022.

Difference in experiences

Decolonisation in Eastern Europe is certainly different from other, especially western, decolonisation experiences. Clearly, there is no one algorithm that would determine in which way a society or country would pursue the process of decolonisation. In Ukraine’s case, but also that of the whole region of Eastern Europe, the initial stage of decolonisation, in the geopolitical sense, showed a return to the alternative centre (in this case the West). In other words, the ongoing westernisation of public (political but also cultural) discourse shows that at least a temporary revision of subordination is now in place. Similar processes were observed in Central Europe after 1989, when the democratic transformation started. At that time among the post-Soviet republics, only the three Baltic states (Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia) developed their own strategies of departing from dependency on Moscow. They opted for both a strong westerninsation and a de-Sovietisation of their states and societies. These experiences, as well as that of today’s Ukraine, show that the so-called third way is not an option and only a strong “escape” to the West can allow for decolonisation to succeed in the region.

The West, on the other hand, shows that it desperately needs a decolonisation of knowledge about Russia and the post-Soviet region as a whole. For this to happen, we need to adopt new standards in academic research into the region and completely free it from the still present Soviet or Russian burdens. This will definitely require the adoption of colonial theory towards Russia, its past and present, which in turn explains why we need to include Russian colonialism into global colonial studies. For the moment this change of paradigm remains to be one of the greatest challenges faced by western academia.

It is certain that a theory is not suffice to create ready scenarios for implementation. Decolonisation is a dynamic and long-term mental process and not a ready solution. Therefore, even when a parliament passes laws it does not mean that the society will immediately stop speaking Russian or abandon Russian heritage and culture. Each country’s case is unique and each country’s decolonisation requires the consolidation of the elite and the society. In Ukraine, for example, we can see that the anti-colonial struggle is marked by both strong nationalism and a strong departure from having any cultural ties with Russia. The Belarusian society, on the other hand, has clearly shown that is not ready to follow in Ukraine’s footsteps just yet. It still has a lot to learn from its neighbour’s experience, which could also be a challenge given its completely different political culture, characterised by great subordination and the withdrawal from public life of a large part of the population. Even more, it is evident that a great majority of the Belarusian society is not even aware of the ongoing and crawling colonisation of their country by Russia. As of now there are no signs of such an awaking nor any resources for it to start taking place.

The end of post-Soviet era

The year 2022 could be seen as the end of the post-Soviet era not only for Ukraine but also Russia. Yet, for this to fully manifest, Ukraine’s victory needs to bring Russia’s unconditional surrender. In addition, for a successful Eastern European decolonisation we need a few things to happen. First, a complete de-Sovietisation of public space and social and political institutions needs to take place. Second, there needs to be a development and acceptance of local version of the Russian language and culture. Just like there is Australian or American English, there could be Ukrainian Russian. Third, there needs to be a complete departure from the “great” Russian culture towards local culture, which should be developed at both the “popular” and high levels. Finally, depending on the state, a collective multi-dimensional identity needs to be developed and rooted. It will be composed of a national (ethnic) identity, a digital identity, gender identity, global and regional identity. These means are a bit radical but not the only ones. Thus if the current anti-colonial approach of the Ukrainian elite and society brings an end to the old matrix, the future decolonisation will need to be grounded on fragmented identities – for example, the incorporation of the Russian-speaking Ukrainians into the new identity project, one that will not include Russia. Such a change would require an appropriate cultural policy to be introduced.

These proposals as radical as they seem are necessary. The changes that they will bring will not only help Ukraine and Belarus but also Russia to depart from the old imperial and Soviet past and to reform, from within, its liberal philosophy and create a true federation. Only these conditions will guarantee that Russia’s revisionism is no longer be a threat to its neighbours.

Anton Saifullayeu is an adjunct professor at the Centre for Eastern European Studies of the University of Warsaw and the editor in chief of the BY UA online portal (https://by-ua-studium.pl/).