Forgotten revolutionaries

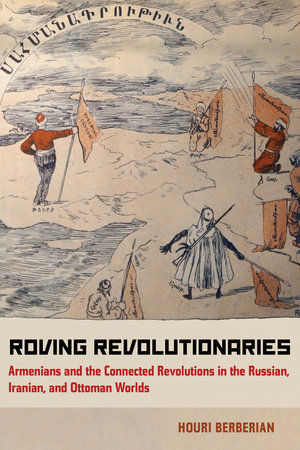

A review of Roving Revolutionaries. Armenians and the Connected Revolutions in the Russian, Iranian, and Ottoman Worlds. By: Houri Berberian. Publisher: University of California Press, Oakland, CA, USA: 2019.

August 26, 2019 -

Kamil Jarończyk

-

Books and ReviewsIssue 5 2019Magazine

In historical literature the Caucasus is often treated as a periphery – a crossroads between Europe and Asia. The same is true in contemporary world affairs, as it is a region often overlooked until tragedy hits. Even when a book is written about one of the peoples of the Caucasus, it usually is a national history that severs the ties between the different nationalities of the three Empires that the Caucuses were divided between: the Russian, the Ottoman and the Persian. Before the First World War, these empires were going through massive transitions, each in their own way with a great deal of uncertainty.

Armenian revolutionaries, who were split between these three empires, fought for their interests and influenced other revolutions with their ideals. The Russian Revolution of 1905 was a revolution that tried to limit the power of the tsar and led to the formation of a national Duma. The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 was a revolution against the unchecked power of the Ottoman Sultan and brought a constitution to the Ottoman Empire. The constitutional crisis of Iran between 1905 and 1911 was a revolution in favour of a constitution and an anti-imperialist revolt against the increasing role of the Russian and imperial governments of Britain and France in their affairs.

Federation of nations

In all three of these revolutions, the Armenians took the side of the revolutionaries. However, the revolutionaries did not seek national liberation in the form of a sovereign state, as many national revolutionaries in the last century have; though influenced by the ideals of liberalism, anarchism and socialism, they saw their place in the wider context of a federation of nations. This was certainly the case in the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire. The only exception was Iran, where Armenian revolutionaries sought a constitution that would guarantee them equal rights in Iran (the reason being the small population of Armenians in Iran). This revolutionary period was crucial to the formation of nationhood amongst the nations of Eastern Europe. Innovations in technology and the emergence of new ideologies played a strong role with these three empires and ultimately led to the revolutions. If given more time to blossom, they could have resulted in a much more peaceful Caucasus.

Roving Revolutionaries: Armenians and the Connected Revolutions in the Russian, Iranian, and Ottoman Worlds by Houri Berberian, a professor in Armenian Studies, takes a different approach to this period of history by connecting the stories of the Arminian revolutionaries across the lands. She highlights the effect that advancements in technology had on the Caucasus and how the revolutionaries were shaped by them. These advancements included the steamboat and the telegraph, but also ideological innovations such as liberalism, socialism and anarchism.

The book is divided into five chapters which puts together the story of the Armenian revolutionaries. Berberian starts by justifying her approach and then covers the reality in which the Armenians found themselves at the turn of the century. It was a world where it took just weeks to travel to other European capitals; a world where one can send messages across the ocean in a matter of minutes; and a world were oil was starting to play an increasing role in more globalised economies. The author also gives a necessary account of the material conditions of the Caucasus and what the reasons were for the emergence of the revolutionaries. She describes how the writings of Karl Kautsky and Rosa Luxembourg sparked debates in Baku and Tiflis/Tbilisi and the way revolutionaries moved across the borders of the empire, which were becoming more porous. She also examines how the revolutionaries got around the official censorship and the banning of their organisations.

The third chapter goes into depth on the influence of constitutionalism and federalism had on the Armenian revolutionaries and how the revolutionaries tried to inject those ideas into the revolutions they were participating in. She also provides a deeper understanding of the monumental and largely forgotten role that socialism played in the budding national movements of the region, and explains the way western socialism was being adapted by Armenian revolutionaries and how it fit the context of the Caucasus with its prominently rural agrarian societies that have no political representation. Finally, the book reflects on the revolutionaries and on the way history has treated them.

A case for connected history

Traditional ways of telling history fall short when you try to explain the development of oppressed nations under the empires of Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Focus often falls on a certain group of revolutionaries whose actions and ideas fit the national mythos of the current nation state. As a contemporary topic, national history is often highly politicised and creates a skewed nationalistic bent on what was a much more varied approach to national liberation, thus leading to the downplay of certain beliefs and actions, or the obscuring of certain revolutionaries or movements altogether. This book sheds light on such movements and parties like the ARF (Armenian Revolutionary Federation) and the SDHP (Social Democrat Hunchakian Party) – both socialist parties but with different tendencies. The ARF played a greater role in all three revolutions than is often acknowledged and is still an active party in Armenia and Lebanon – although they have changed a lot over the last century.

Berberian also illustrates just how connected the Armenian diaspora were with the example of one of the founders of the ARF. Rostom (his real name Stepan Zorian) devoted his life to revolution where he travelled across Europe. He spread revolutionary ideals amongst his compatriots and secured sympathy and support throughout Europe by attending international socialist events in Europe. A map of Europe and the Middle East is included in his travels between 1893 and 1918, where he visited over 20 cities across the whole map. In the second half of the book, Berberian goes into detail about the ideological milieu in the Caucasus at the turn of the century, and how the revolutionaries tried to fit the liberation theories of constitutionalism, socialism or federalism to their situation.

The Armenian revolutionary organisations did not just reach out to Armenians. In the oil fields of Baku where many Iranian migrants worked, they would see and sometimes take part in Armenian-organised socialist activities, such as union strikes and collective bargaining. One can draw a direct line between the Iranian migrant workers in Baku and the popularity of constitutionalism in Iran in 1905. The book also covers Armenian activity in all three revolutions. In Iran they sent an armed force of Armenian revolutionaries that played a crucial role in key battles of exchange – like equal rights of the Armenian minority in the Ottoman Empire and for arms to be smuggled from Iran into other parts of the Caucasus.

In Russia, they helped cut railroads and took part in organised labour struggles that were taking place throughout the Caucasus. In the Ottoman Empire, they negotiated and supported the Young Turks in the overthrow of the Ottoman Sultan and the reinstatement of the Ottoman constitution, as well as advocated for Armenian rights and for a federative Ottoman state. These struggles were not disconnected from one another, and to write about the role the Armenians played in all of them is one of the best ways to reach a more holistic view of that period.

Contemporary issues

The current state of the Caucasus, after the First World War and after the atrocities and suppression, seems to have fundamentally split as a result of the blossoming revolutions of the pre-war Caucasus. The idea of a Transcaucasian federation with equal rights for the three main groups seems like an alien concept now considering how the region looks today. Armenia, in particular, is very different than it was a century ago. There is no division amongst the three empires – there is only the post-Soviet state of Armenia which is homogeneous both ethnically and religiously. There is no issue regarding a federation or workers’ rights which were at the forefront of politics. In this way, one can ask what connection does contemporary Armenia have with the revolutionary organisations and the people who formed them?

This is an area where the book could have gone further. The book only covers the material and ideological factors, but it is limited in how it relates to the Caucasus today. For western historians, however, such a work is valuable. Yet for those readers interested in how history provides the needed context for current affairs, this book might lead to disappointment. The book abruptly ends at the start of the First World War and argues that only after the Armenian genocide did everything drastically change. One is left wondering – what is the lasting impact of these revolutions? What influences, if any, do they play in the modern world? Perhaps this is a task for further historians and those specialising in Armenian Studies.

Kamil Jarończyk is a student of International Relations and Russian area studies and is an editorial intern with New Eastern Europe.