Towards Improved French-German Cooperation in the EU Neighbourhood

April 23, 2013 -

David Rinnert

-

Bez kategorii

doc.jpg

Until now, France and Germany – the “motor” of European integration – do not agree on how to address the ongoing economic and financial crisis, which remains the most debated policy issue within the European Union. Clearly, increased effectiveness of EU policies on the crisis and beyond requires more convergence of visions and proposed policy solutions especially between France and Germany. This process of convergence between the two countries can only be successful when there is a stronger political will to improve common understanding and reduce differences in interests.

The very same is true for EU foreign policy and neighbourhood policies, a field in which France and Germany fail to substantiate their relations. The lack of French-German cooperation on the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) has been especially damaging for the EU in the cases of Libya, Syria and Ukraine, but also beyond. To make a long story short, France and Germany are the driving forces behind two EU interest groups, the “pro-South” countries aiming at improving the relations between the two banks of the Mediterranean Sea, and the “pro-East” group, advocating for the prioritisation of transformations in the post-Soviet space.

Should the EU prioritise transitions of its European neighbours in the East, where the risk of political and economic stagnation is high, and the geopolitical fate still unclear? Or should it give priority to the Arab Spring and its consequences, dealing with the southern neighbours of Europe? Obviously, asking the question in such a way leads to a misconception of European interests. The “more for more” principle, introduced in 2011, gives guidance in this regard. Based on a more rigorous conditionality, neighbouring countries shall be judged by their democratic performances and not by their geographical location. However, the eurozone crisis and ongoing disagreements between France and Germany over the neighbourhood have hampered real improvements in recent years: it seems that the two countries share the same bed (neighbourhood), but not the same dream (political vision).

Improving foreign policy and neighbourhood policies in particular is a difficult task, and the French-German tandem should focus on realistic first steps to overcome previous disagreements. In this perspective, Moldova, as one of the most promising countries in the eastern and southern EU neighbourhood in terms of Europeanisation, could and should be a laboratory for strategic cooperation between France and Germany. Specifically, a common initiative on the resolution of the unsolved Transnistrian conflict in this country would represent a chance to overcome previous French-German divisions, as both countries’ interests in this conflict overlap more than anywhere else in the EU neighbourhood.

The short military conflict over the small territory of Transnistria, located to the East of the Dniester, erupted in 1992 within the newly independent Republic of Moldova, claiming the lives of more than 700 people. Contrary to other conflicts in the post-Soviet space, the Transnistria war did not break out because of ethnic differences between the two territories. Nevertheless, despite the initiation of the so-called “5+2 talks” under the auspices of the OSCE (including Moldova, Transnistria, Russia, Ukraine and the OSCE, with the United States and the EU as observers), progress towards conflict resolution was slow over the past decades. Beyond the OSCE conflict resolution process, informal initiatives such as the Meseberg Memorandum of 2010, involving Germany and Russia, also failed to deliver the expected results. Although some progress has been made in 2012, Transnistria might soon become a missed opportunity if no concerted action takes place, as the current political crisis in Moldova evolves and as Russia increases its engagement in the conflict.

There are a number of arguments why Transnistria would be the best test case for a strategic French-German initiative in the EU-neighbourhood. France has an interest in increasing its engagement in Transnistria, as it is the only so-called “frozen conflict” in the post-Soviet space in which it is not involved, while Moldova is a neighbouring country to France’s closest ally in the region – Romania. Also, to date, French policymakers seem to have neglected the fact that Moldova is the EaP country where the French language and cultural presence is most developed. It was not by chance that France, together with Romania, founded the Friends of Moldova Group in 2010. On the other hand, Germany is already the key EU player in Transnistria, underlined by its ongoing commitment and visits from highest-level officials such as Angela Merkel in 2012.

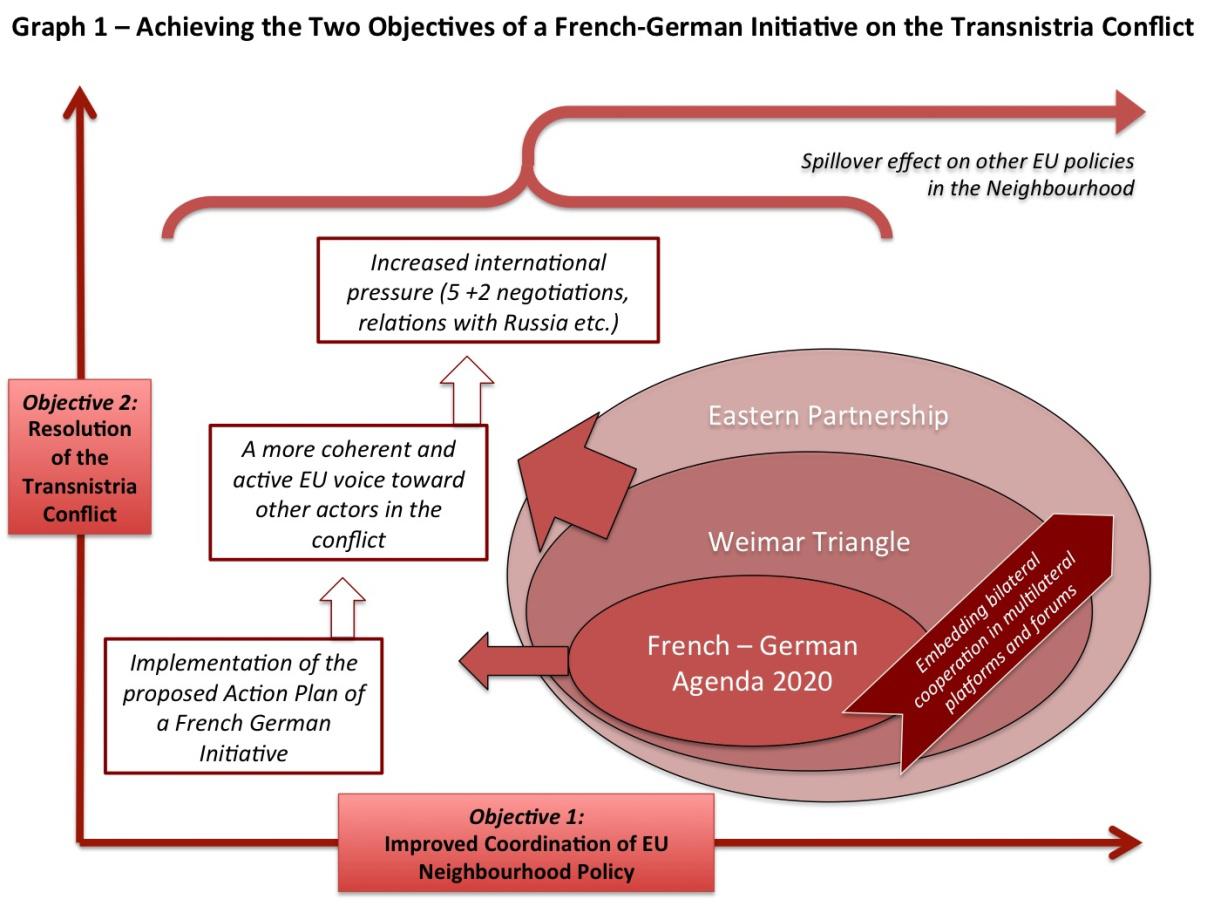

A French-German initiative in the Transnistrian conflict would aim at the achievement of two major objectives, namely overcoming the southern vs. eastern neighbourhood division within the EU, and improving the situation in the Transnistrian conflict, allowing for a fully-fledged and acceptable conflict resolution in the mid-term. Both objectives could be achieved through making use of several already existing platforms such as the French-German Agenda 2020, the Weimar triangle and the Eastern Partnership.

An action plan that could be implemented via these platforms should focus on several aspects, among them developing people-to-people contacts, making use of the French-German model of reconciliation, business-to-business contacts (notably in the area of energy) and cultural policies. The creation of a Moldovan-Transnistrian youth office, a town/village twinning mechanism, a mechanism allowing for students exchanges or the organisation of an annual prize for an initiative supporting reconciliation, are some examples for specific steps in this regard. Similarly, the role of civil society in the conflict should be promoted through support for local and sectoral initiatives, while at the same time scaling up measures against corruption. Last but not least, current negotiations on a Moldovan-EU DCFTA and visa liberalisation could be used as a tool for reconciliation.

Nearly ten years after the ENP was passed, France and Germany have to find a common denominator in the EU neighbourhood, and Transnistria would arguably be the best test case in this regard.

Florent Parmentier, PhD, is a programme director for the Master of Public Administration in Sciences Po, Paris. He specialises and lectures on European neighbourhood policy (mainly the Eastern Partnership and Moldova) and energy politics.

David Rinnert works with the German Development Agency (GIZ) in Moldova and is an independent researcher on post-Soviet transitions.

The authors have also recently published a full-length policy brief for IDIS “Viitorul” entitled: Finding Common Denominators in the Eastern Partnership region: Towards a strategic French-German cooperation in the transnistrian conflict. You can download the brief here: http://www.fes-moldova.org/media/pdf/Policy_Policy_Brief_2013_1.pdf