In the grip of over-inflated expectations: Ukraine must avoid the “Orbanization” of its EU and NATO accession

An internal conversation about EU and NATO membership should take place in Ukraine to avoid the “balkanization” and “Orbanization” of the country’s accession talks and integration. A consensus on not abusing EU and NATO topics in political fights must be reached, as the stakes and risks are incomparable to those in Hungary and the Western Balkans in light of the ongoing war.

February 20, 2024 -

Dmytro Tuzhanskyi

-

Articles and Commentary

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and attends a joint press conference with Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Kyiv in May 2023. Photo: Review News / Shutterstock

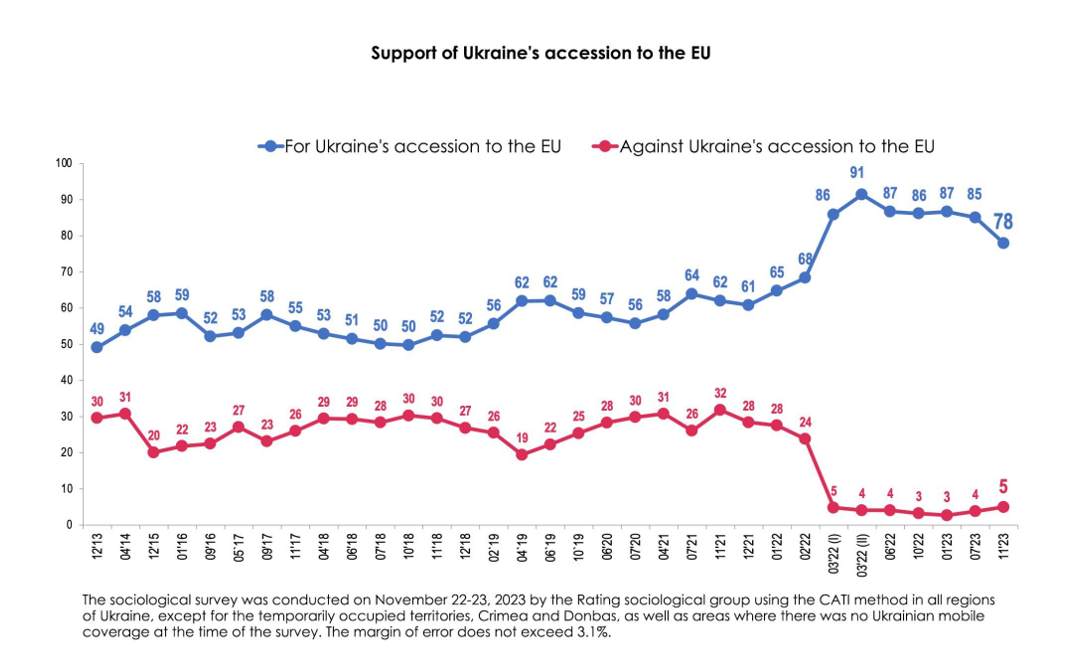

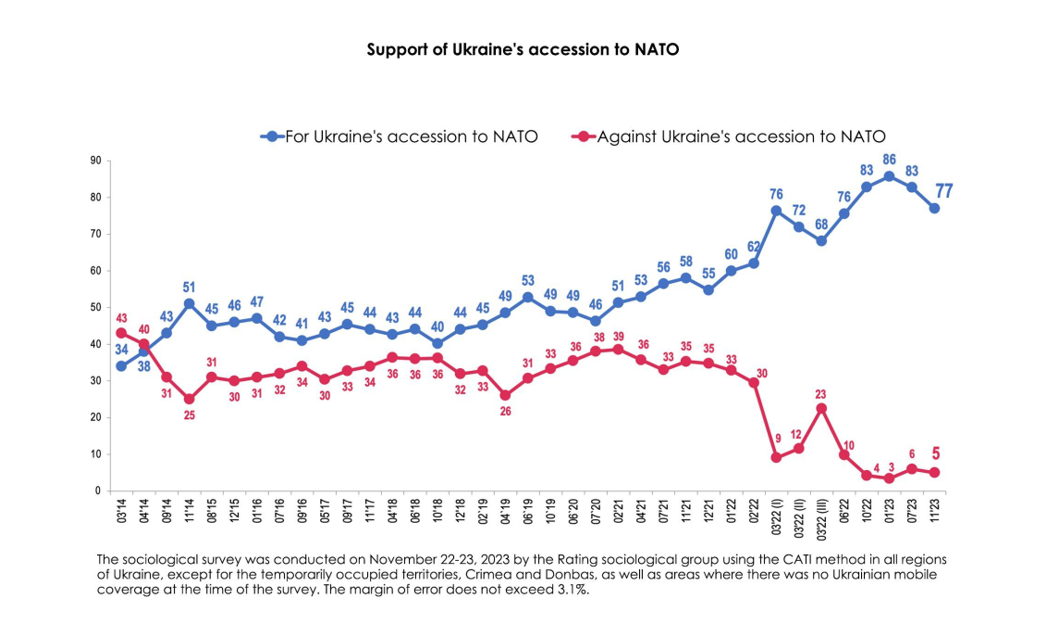

Since 2014 the level of support for Ukraine’s accession to the EU and NATO has grown considerably. Since February 2022 and the Russian full-scale invasion, it has reached the unprecedented levels of 80 to 90 per cent support for both.

Such a reality concerning public opinion on the EU and NATO could be called ideal, or at least certain. However, the problem of Ukrainians’ expectations in this context is obvious. These expectations are now incredibly high across society.

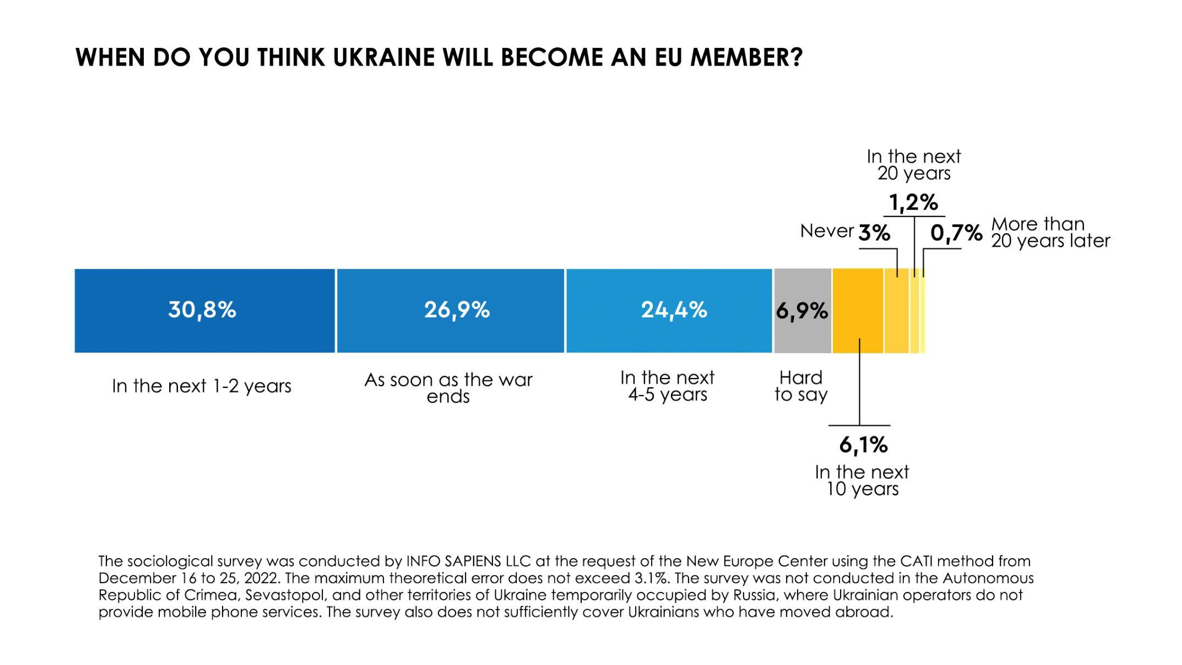

As of December 2022 (a year before the decision to open negotiations), 30.8 per cent of Ukrainians believed that Ukraine would join the EU in the next one to two years. Another 24.4 per cent thought the country would become a member as soon as the war ended. Finally, 26.9 per cent thought this would occur in the next four to five years.

As of December 2023, 19.2 per cent of Ukrainians expect Ukraine to join NATO in full at the Alliance’s next summit in Washington. In contrast, a total of 46.3 per cent expect the country to be invited to join NATO, either with or without an accession process.

For Ukraine now, EU and NATO accession is not just a matter of pure geopolitics but a choice between Russia and the West. It is also at its core an existential war for the independence and survival of an ethnic and political nation, as well as a process of decolonization away from Russia.

As of June 2023, 72.8 per cent of Ukrainians said that it is unacceptable to give up on joining the EU in exchange for an end to Russia’s aggression. Around the same amount of respondents – 71.7 per cent – believed this regarding NATO accession.

Traps of time and discourse

It is obvious that Ukraine will not be able to join the EU and NATO in the short term, i.e., in the next one to two years. Even in the medium term – four to five years – this process looks problematic.

The European Council President Charles Michel’s announcement that 2030 would be the next year of enlargement does not correspond with the expectations of 24.4 per cent of Ukrainians, although it looks like the most optimistic date from the point of view of the current forecast.

In addition, it is important to be aware of the threat of additional disillusionment, which lies in the expectation of a quick victory in the war. As of December 2023, more than half of Ukrainians (58 per cent) believe that Ukraine will win the war in the short term. Additionally, six per cent thought this would happen in the next few months and 21 per cent by summer 2024. Another 31 per cent thought this would happen in one to two years and in the medium term (three to five years) 15 per cent of respondents viewed victory as likely.

A long-term war with Russia is likely to serve as an additional factor for disillusionment regarding accession to the EU and NATO. This is especially true taking into consideration the fact that both alliances have already publicly and explicitly stated that it is impossible for Ukraine to join the EU and NATO fully until the war ends.

This narrative connection and the inflated expectations of Ukrainians regarding the EU, NATO and victory in the war are ideal grounds for various conspiracies, such as “the West does not want Ukraine to join the EU or NATO, so it helps just enough to ensure that Ukraine does not lose the war, but also does not win it.” Such a narrative is already very popular in Ukraine, especially among elites.

There is another big trap that has been created by the unprecedentedly high level of support for Ukraine’s membership in the EU and NATO, as well as the absence of critics of this course. It creates the illusion that there is nothing to discuss and learn about the EU and NATO as such a discussion is not necessary. It therefore appears that diplomats and bureaucrats will simply do the rest of the work. This is especially true now that accession talks have been opened.

In this regard, two cases from 2023 are illustrative. Both concern the adoption of two so-called European integration laws. The first is about the financial monitoring of politically exposed persons (PEPs), and the second is about changing the legislation on ensuring the rights of national minorities. In both cases, the government’s key argument for adopting the draft laws in their current form was that they were necessary to open negotiations on EU accession.

This approach provoked public criticism. For example, some believe that Ukraine is making unnecessary and destructive concessions, saying that the PEP law could almost destroy Ukrainian public services. It also appears for these people that the new law on minority rights could undo all previous achievements in terms of de-Russification, as well as the protection of the Ukrainian language and nation-building.

In the end, the new draft law on the rights of national minorities was submitted to the parliament, with some changes from virtually all factions. It was then supported by 317 votes. This law was actually about changes to the legislation that Hungary had been demanding for the past five to six years. This was used as an excuse for Budapest to block Ukrainian integration with the EU and NATO, as well as pro-Russian rhetoric about the oppression of minorities in Ukraine.

What can be done

Given these public sentiments and discourse in Ukraine on EU and NATO topics, it is important for Ukrainian decision makers and their western partners to do the following:

- Initiate and conduct additional qualitative research on how public opinion and discourse on EU and NATO accession in Ukraine is shaped, in particular, by focusing on:

– studying such media platforms as Telegram and TikTok, given the potential influence and depth of penetration of Russian, pro-Russian or other malign disinformation on the EU and NATO topic.

– the impact of leading western media publications on shaping narratives and agendas in the Ukrainian media space. This need is justified by the growing trend of sceptical materials concerning the war and western support. It is clear that negative coverage on topics like Ukraine’s accession to the EU and NATO is growing in these media outlets.

– the identification of interdependencies regarding public perception and narratives related to the topic of Ukraine’s accession to the EU and NATO, as well as other critical issues such as the war, mobilization, peace negotiations, security guarantees, unpopular reforms, etc.

– studying the mood of certain target audiences in Ukraine, such as farmers, government officials, etc. This will allow us to better understand the protest potential of sensitive target audiences. A good example in this regard is Poland, where there is one of the highest overall levels of support for Ukraine’s membership in the EU in Europe. Despite this, many of the country’s farmers and truck drivers are turning into a key protest force on this issue.

– identifying narratives and conspiracy theories popular among Ukrainians, whether of Russian or any other origin, that question the feasibility of Ukraine’s accession to the EU and NATO. Strategies and tactics should subsequently be developed to counter these influences. One example of these narratives and conspiracy theories is the idea that “Joining the EU will destroy Ukrainian agribusiness.”

This will allow for a deeper understanding of the topic, which at first glance looks unambiguously positive and problem-free in terms of public support and approval.

2. To plan and deliver a series of strategic communications campaigns that would balance the over-inflated expectations of Ukrainians in several aspects:

- on the timeline of Ukraine’s accession to the EU and NATO.

- on the format of negotiations on Ukraine’s accession to the EU and NATO. In particular, to clarify in the public discourse as much as possible that it is not so much about negotiations as about Ukraine’s adaption to all possible “club rules” and the need for certain concessions as a fair price for the country’s overall success in the EU and NATO.

This communication should be aimed at changing the discourse from being focused on expectations to a discourse of collaboration and inclusion.

Given the sensitivity of the issue for politicians, this task implies the greatest possible involvement of the expert community and opinion leaders with high recognition and credibility to deliver “bad news” and “rude truth”.

Former western politicians and influencers who support Ukraine, such as former Polish President Aleksander Kwasniewski, former Slovak Prime Minister Mikulas Dzurinda, and former Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaite, could play this role. Other possible figures include historian Timothy Snyder, former European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso, intellectual Anne Applebaum, former Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, former Romanian President Traian Basescu, former NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen, and many other former top-level officials from across the West.

3. Strategic communications in cooperation with civil society could help strengthen public dialogue in Ukraine about the EU and NATO in the context of understanding these alliances and the logic and specifics of their functioning. Other topics include the specifics of accession, as well as the short-term difficulties and long-term benefits for Ukraine. Such a dialogue should compensate for the actual absence of debates on joining the EU and NATO by focusing attention on education, experience, and personal and social adaptation.

It is important that these discussions are not only aimed at the general public, but are tailored to the specific target groups and sectors that will be the focus of the negotiation process. We are talking about specific industries and sectors, such as agriculture, transport and logistics, IT, forestry, construction, light industry, local government, etc. This is important for the formation of new sectoral coalitions that would advocate for EU and NATO membership based on pragmatic arguments.

At the same time, accession to the EU and NATO cannot be discussed so simply as it is now by the Ukrainian government or its western partners. It is clear that unpopular reforms will be required in the negotiation process.

4. The 2024 European Parliament election campaign could be used as an occasion for an advocacy campaign in Ukraine and the EU in the style of “Ukraine in the EU: Stronger together”, “Peace is… Ukraine in the EU”, “EU needs you”, or “EU needs Ukraine”.

Key components of the campaign could include countering disinformation narratives that may cast doubt on Ukraine’s accession to the EU, as well as balancing anti-Ukrainian and Eurosceptic rhetoric. Ukraine could also be integrated into the EU’s agenda as a future member while mobilizing Euro-optimist voters and educating Ukraine about EU internal policies. Finally, it would be good to build critical and constructive perceptions of the EU’s “internal kitchen” in Ukraine while also developing a Ukrainian vision of EU reform before the country’s accession.

The NATO summit in Washington could be used in a similar way to balance the high expectations of Ukrainians regarding accession. This could be done alongside a quality discussion on future membership, security guarantees and cooperation with the Alliance.

5. Elaborate narratives would help ensure that support for Ukraine’s accession to the EU and NATO does not depend on the duration of the war against Russia, the accession negotiation process, or internal reforms in the EU and NATO.

The updated narratives should explain and rationalize the fact that Ukraine has no alternative to joining the EU and NATO, and could be formulated like this: Ukraine’s survival as a sovereign and democratic state depends on its accession to both the EU and NATO.

Dmytro Tuzhanskyi is the director of the Institute for Central European Strategy.

Please support New Eastern Europe's crowdfunding campaign. Donate by clicking on the button below.