Orwell’s warning of totalitarianism for today

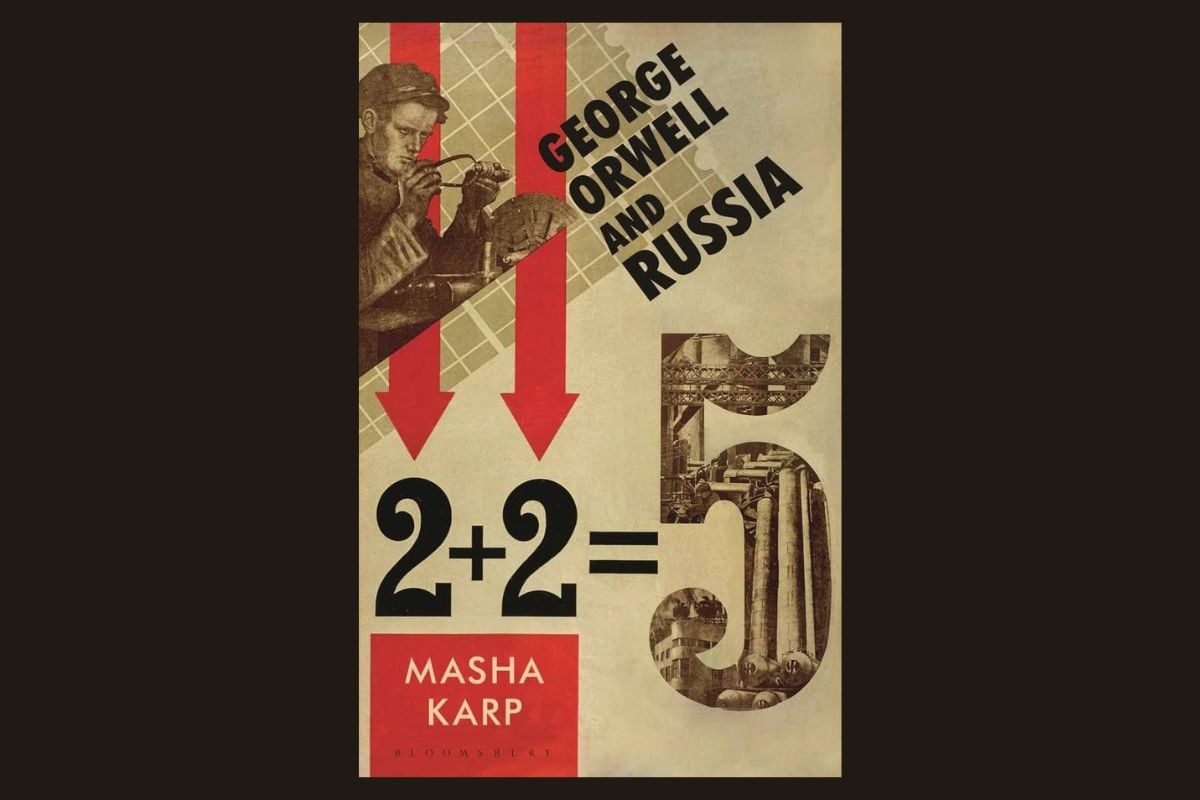

A review of George Orwell and Russia. By: Masha Karp, published by Bloomsbury Academic

September 11, 2023 -

Luke Harding

-

Books and ReviewsIssue 5 2023Magazine

In the mid-1970s some of Masha Karp’s friends gave her a copy of an illicit text. Over a couple of days she devoured it. “Is it safe to keep the book at home overnight?,” her mother asked at the family’s flat in Leningrad. Her mother knew that searches and arrests inevitably happened at night. True, this was now the Brezhnev era. But the experience of Stalinism cast a long shadow.

The novel was George Orwell’s forbidden Nineteen Eighty-Four. It was not until 1988 and perestroika under Gorbachev that the Russian authorities allowed it to be officially published. Karp, a future political journalist, was dumbstruck by the obvious parallels between the “bleak and cruel life” endured by the book’s protagonist, Winston Smith, and life in the Soviet Union.

Orwell’s intuition

Orwell had rendered in fiction the experience of individuals under totalitarian rule on the “wrong side of the Iron Curtain”. He understood the communist system of organised lying, the dumbfounding back-to-front slogans, and the state’s falsification of history. He knew the gloom and squalor. And he comprehended the secret interior world of those oppressed: the enforced duality of a private self and a conformist public one.

And yet Orwell never set foot in the USSR. Nor did he read Russian. When the October Revolution erupted in 1917, Orwell was a 14-year-old schoolboy at Eton, in Berkshire. Seen from the perspective of a communist citizen, he was an outsider. As Karp writes, Eastern European readers who were able to get hold of samizdat versions of his last novel, between the 1950s and late 1980s, all wondered the same thing: “How did he know?”

Karp’s book, George Orwell and Russia, answers this question. It is published in the context of Vladimir Putin’s full-scale attack on Ukraine, which has made the question on Orwell brutally pertinent. The similarities between today’s Russia and Orwell’s Oceania are overwhelming. Putin’s dictatorship is killing thousands of people and razing cities in a war that cannot be called a war, as it was launched for spurious reasons. As Karp observes, the Russian state is sinister and absurd.

A leading Orwell scholar and a translator of Animal Farm into Russian, Karp points to key figures who influenced the young Eric Blair’s views. They include his mother’s eccentric sister Aunt Nellie, a communist and enthusiast for the international language Esperanto. In 1923, in her early fifties, she met Eugene Lanti, the founder of a global Esperanto association. Its aim was to overthrow the capitalist order. Lanti visited Petrograd full of radical fervour. He was disappointed by what he found: poverty, prostitution, bureaucracy and a Bolshevik ruling class. By the late 1920s he concluded that Moscow was uninterested in a progressive world revolution. It wanted to promote the “national state” interests of Stalin’s dictatorship. The USSR had become a nightmarish “prison”, he told Orwell, who at the time was inclined to believe it represented definitive socialism.

Naïve idealism

Another person who changed his view was Myfanwy Westrope, Orwell’s London landlady between 1934 and 1935. Westrope was a suffragette, pacifist and Esperantist. She travelled in 1931 to the Soviet Union and – thanks to Esperanto – was able to talk to ordinary citizens. One of her contacts, a professor in Omsk, subsequently disappeared, leading her to think wrongly that he had been shot. In fact, terrified of arrest, he broke off contact.

Westrope and Lanti were disillusioned by what they found in the land of the Soviets. Karp points out that their negative attitude was unusual among members of the British left. Other representatives – George Bernhard Shaw, Beatrice and Sydney Webb – returned from trips to the Soviet Union proclaiming they had seen the future. All were guided by “ideology and considerations of internal politics”, Karp writes, rather than what Orwell dubbed “the moral nose”.

In a 1935 letter, Orwell complained of “English intellectuals who kiss the arse of Stalin”. He regarded them as little different from fans of Hitler and Mussolini, “all of them worshipping power and successful cruelty”. Their ignorance and naïve idealism led them to ignore the actual horrors of communism, including the state-engineered 1932-33 famine in Ukraine (Holodomor), in which around four million people died, and the disaster of agricultural collectivisation.

It was Orwell’s time in Spain that had the biggest impact on his political views, and which led to an enduring rift with the pro-communist left. In late 1936 he went to Barcelona and joined the POUM militia, a small party in the popular anti-fascist coalition. It was one of three groups fighting in the civil war: revolutionary anarchists who controlled Barcelona; Spanish communists directed by Moscow; and General Franco’s fascists.

In May 1937 Stalin decided to crush POUM and its supporters, many of whom had spent months fighting in freezing trenches against a common fascist enemy. Orwell was appalled. The Spanish police, at the behest of the NKVD, arrested POUM leaders. Several were tortured and executed while others disappeared. Orwell’s hotel room was searched. Letters about his book, The Road to Wigan Pier, were confiscated and ended up in a Moscow archive. His experiences in Spain – of Soviet mendacity and ruthlessness – played a key role in his later fiction.

“His writer’s sensibility helped him to imagine the feeling of the inmates,” Karp remarks. She notes that Orwell – who got out of Spain just in time – was able to identify with those who were Moscow’s victims. He had direct experience of communist practices: censorship, torture, frame-up trials, and the activities of the secret police.

In the following years Orwell frequently struggled to print what he thought about the Soviet regime. It took him three months in 1944 to write his “fairy story’” – Animal Farm – but another six to find a publisher. Editors were reluctant to bring out books which criticised Britain’s valiant war-time ally. And the English intelligentsia swallowed and repeated Russian propaganda, Orwell complained, much of it fuelled by Soviet agents.

One of Orwell’s influential friends was the Vienna-born sociologist Franz Borkenau. A convinced Marxist, Borkenau wrote secret reports for the Comintern in Berlin. In 1928 he broke with Moscow, which had identified Germany’s Social Democrats rather than its Nazis as the main enemy. Orwell and Borkenau reviewed each other’s books. It was Borkenau who argued that Bolshevism and fascism were slightly different specimens of the same dictatorship.

Old habits

Seven decades later, authoritarian habits returned to Russia. A handful of experts, human rights activists and journalists tried to draw attention to the Kremlin’s reversion under Putin into a repressive war state. Karp was one of them. “They were not heard,” she laments. There was plenty of evidence: the murder of critics at home and abroad, two Chechen wars, and the 2008 invasion of Georgia. Of course, later this was followed by the 2014 annexation of Crimea and Putin’s covert takeover of a part of the Donbas.

Karp suggests that it was western analytical error and complacency which made Putin’s attack on Ukraine possible. Contemporary policy makers and politicians were guilty of “an incredible lack of political judgement coupled with unfettered greed”. Deputies, British peers and other unscrupulous individuals “grabbed profits” offered by the Russian authorities. On top of this came Russia’s “skilful propaganda” and “deep infiltration” of our democracy.

Karp’s book is fascinating, well-written, timely and original: a necessary reappraisal of what Orwell’s work meant, and its relevance today. She is scathing about the mistakes made by the West in failing to see Russia “as it is”, in Orwell’s indispensable phrase. In recent years, she notes, the British media interpreted Nineteen Eighty-Four as a message against surveillance overreach, rather than as a warning about the ever-present “danger of totalitarianism”. Totalitarianism, Big Brother-style dictatorship, “War is Peace”, and the “shifting phantasmagoric world” described by Orwell are back. Not that they ever went away.

Luke Harding is a British journalist with the Guardian and served as the Guardian’s Moscow correspondent between 2007 and 2011. His latest book Invasion: Russia’s Bloody War and Ukraine’s Fight for Survival, shortlisted for the 2023 Orwell Prize, is published by Guardian Faber.