My Father Was a Famous Polish Writer

An interview with Matthew Tyrmand, the son of the famous Polish writer and populariser of jazz Leopold Tyrmand. Interviewer: Filip Mazurczak

February 18, 2014 -

Filip Mazurczak

-

Interviews

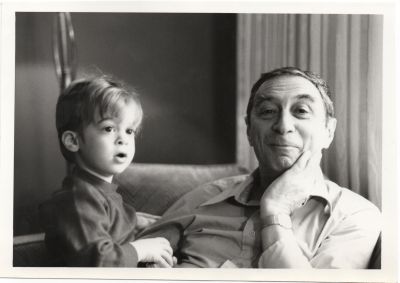

Photo courtesy of Matthew Tyrmand

Why did the American-born son of a great Polish writer with a diploma from the University of Chicago decide to come back to Poland? What are your plans regarding Poland in the near future?

It really was a confluence of events that brought me back to Poland and led to my deeper engagement with the nation. As I discuss in the book, ironically – or maybe not that much – it was a girl that first got me to visit. I was working a lot and didn’t really go away for longer than long weekends and always had wanted to go to Poland for a good chunk of time when I did make it over there. My first few times were only long weekends but I came with enough frequency that I got to know the country fairly well. The first time I came to Poland was a week before the April 10th 2010 Smolensk airplane accident. I then came half a dozen more times before being invited by the town of Darłowo in spring 2012 to be present for a commemoration of my father who set his first novel Seven Long Voyages there. From then it kind of snowballed. The idea for the book Jestem Tyrmand, syn Leopolda, (“I Am Tyrmand, Leopold’s Son”) published by Znak in October 2013, was born on that trip when I met Kamila Sypniewska, a journalist who became my co-author. I received Polish citizenship in 2012 and as I visited more I began to see a society moving in a positive direction which was in stark contrast to the United States. But right now the government needs to be reined in for my optimism to continue unabated. With respect to my future plans in Poland, I am being open-minded and patient for the right opportunities, projects and investments. I inserted myself into the public debate in a few arenas, most notably economics and politics. I worked with Forum Obywatelskiego Rozwoju (“The Forum for Civic Development”) and Leszek Balcerowicz, the author of Poland’s transition from socialism to a free-market economy, in calling out the Tusk government’s pension nationalisation. My future in Poland is somewhat predicated on a ratcheting back of the big government and socialistic approaches to everything that seem to permeate all European politics. Poland is starting to catch up in trend and that worries me. Assuming the ship is righted, which I do believe is possible (unlike in America at this stage), then it is likely there will be many great ways to take part in the long term migration from post-communist society to one that is analogous with Western European nations. My expectation is that eventually Poland will be a better country to live in than Spain, France and other insolvent or structurally broken “developed” economies.

Your Polish-born father died when you were a small child. Was Polish culture, for which you feel an obvious affinity, present in your home growing up?

Not at all. My affinity was generally more academically derived. I knew my father’s personal history and legacy so I always wanted to get closer to that and so I tried to consume what I could of the culture in New York City and Chicago but it certainly was not present in the home at all beyond my mother having occasional visitors that were my father’s friends from Poland.

Both my parents and grandparents read your father’s books in communist Poland, and his works are still popular among Poles. However, while your father lived as an émigré in the United States and wrote for such noted publications as the New Yorker, he is not well-known there. Do you plan on popularising Leopold Tyrmand’s work outside Poland?

Both my parents and grandparents read your father’s books in communist Poland, and his works are still popular among Poles. However, while your father lived as an émigré in the United States and wrote for such noted publications as the New Yorker, he is not well-known there. Do you plan on popularising Leopold Tyrmand’s work outside Poland?

Outside of some academic political and cultural philosophy circles, he certainly is not that well-known, despite the intellectual circles he travelled in. He was definitely ahead of his time and he was saying a lot of the things the neo-cons said before there even was such a label. He was very hawkish on defeating communism. But I think if he were alive today he would be more of a libertarian as he abhorred the centralisation of power that comes from growing government and the oppression that results from the regulatory bureaucratic state. He also strongly believed in free markets as command economies always result in less choice. One of the principle reasons he fell out of vogue was that he had a big split with the NYC literati in the late 1960s and early 1970s when they lurched so far left that they became counter-cultural progressives and haters of core American values with serious socialistic predilections. These media elites took to hypocritical elitist values and never looked back and have since become ever more complicit in the propaganda of paternalism. After breaking with the “wine and cheese” crowd he founded the Rockford Institute in Illinois and engaged the battle of ideas from a markedly more conservative position. The short answer to popularising him outside Poland is yes. His diary, which is his greatest work along with The Man with the White Eyes, undisputedly his greatest novel, is being published in English in March 2014 by Northwestern University Press. The translation is great and I was recently able to read it for the first time thanks to the translators Andrzej Wróbel and Anita Shelton. This was a very gratifying experience for me, being able to read his thoughts put on to paper at a stage in his life when he was roughly where I am now. It was powerful seeing his experience that much more deeply. We will see what happens with his diary. I am more interested in having his English writings anthologised and translated into Polish as I know there is more demand and so much curiosity as to how his thinking evolved from the time he wrote all his novels (in Polish) in his earlier years.

What do you think is your father’s books’ relevance today?

I think they are relevant in a sense that they are timeless. People are inspired by those who faced down oppression and did not bend, yield or break. My father possessed a stubbornness that was truly of the scale of a Greek epic, as my mother will tell you. In the world in which he lived the degree in which nothing could coerce him to say something he did not believe, no matter what the penalty or the reward, was highly unique. Add to this that he was a big personality, with the socks, the sunglasses, the clothes, the jazz, the wit, the eloquence, the openness, the womanising, the astute analytical prose and his provocativeness. Everything he did was motivated by his desire to thumb his nose at the authorities that would censor him and tell him how to be. He maintained this flashiness while living in grey, drab, limited and oppressive communism. I think his personality did its part to make his writing, which was damn good, remain relevant. It’s a great legacy and I hope I can help catalyse further interest in it.

In previous interviews, you have expressed your love for Warsaw. Władysław Szpilman, the virtuoso Polish pianist who survived the Warsaw Ghetto and later the Warsaw Uprising and the destruction of the city, initially titled his best-selling memoir filmed by Roman Polański as The Pianist as The Death of a City. Do you not feel certain sadness when in Warsaw, that the city is lacking its once-great glory as 85 per cent of the city’s buildings were destroyed during the Second World War and that Warsaw is the ghost of a city?

I think Warsaw has more than its share of ghosts with its sad and violent history. There are certainly neighbourhoods where you can feel its history more than others. But I would not call it a city that is lacking its “once-great glory.” I see one of the most vertical skylines in Europe with the top architects in the world vying for projects. I see many thriving neighbourhoods with great character and still great architecture and many districts transitioning or developing on the fringes. I see a lot of businesses small and large competing in a marketplace laden with choice. There are a lot of great and positive trends in Warsaw: an optimistic energy, fun-loving and independent-minded youth and varied and interesting environments at all times. I really love this city.

While your father was fully assimilated into Polish culture, he was of Jewish ethnic origins. How do you see the current state of Polish-Jewish dialogue and how do you think you could contribute to it?

I think Polish- Jewish dialogue is pretty good. The new Museum of the History of Polish Jews has gotten a lot of investment, interest and praise. There is certainly a desire for a large section of the Poles to learn about this history which was such a material segment of Polish history. Of course, there will always be fools who are bitter and resentful for no rational reason or because they feel marginalised so they want to lash out at a scapegoat for whatever injustices they see in the world. This is everywhere and has been experienced with every minority or transitional group in some place or time. I personally don’t take it seriously and when I read anything that could be deemed offensive my desired approach is to argue with these idiots but I have found I would not have time to sleep due to the volume of internet trolling in Poland so I just laugh instead. The English poet George Herbert said that “living well is the best revenge”. I am not sure what role I will take in the area of Polish-Jewish relations. But my inclination is that it will not be an in depth one as I am not all that connected to the Jewish faith. My priorities lie within other areas of inquiry and discourse like politics and economics and in promoting the artistic legacy of my father as well as hopefully investing in Poland’s growth.

You have become engaged in Poland’s political life. Why did you choose to publicly support Jarosław Gowin’s Poland Together (Polska Razem Jarosława Gowina) party?

As I have mentioned, I am pretty disgusted with the state of the two entrenched political parties in Poland today, as are over 70 per cent of Poles according to one study I read. Both the left and the right are socialist. They are hostile to business and entrepreneurs. Government almost invariably destroys any chance of these trends taking hold if left to expand itself unchecked. It crowds out the productive segments of the economy by allocating resources much less efficiently than the marketplace. When I see some in the Western press talk of the “Tusk government” as centre-right I always think to myself that the only thing centre-right about Tusk is what side of the road his chauffeur drives him on. Poland needs a bona fide libertarian who believes in smaller government and lower taxes and sees the best way to get the economy to expand and the society to thrive is to do as little as possible in protecting rule of law. As Hippocrates said, Primum non nocere (“First, do no harm”). And any intervention by the government is invariably harmful and a perversion of rational and competitive free market forces. With respect to Gowin, the most important thing is that he is a good man. He is honest and possesses a lot of integrity and conviction in his ideals. This is a rarity in the current EU and in Poland. He has varied experiences in different sectors of society and the economy, and most importantly he recognises the importance of freeing markets so that the productive forces are unleashed for everyone’s benefit. What he did in a few cities with fighting taxi licensing schemes being foisted on entrepreneurs by the city was an inspiring action and demonstration of a commitment to fighting for competition not against it. I don’t agree with everything Gowin stands for and suggests but given his personal temperament there is more than enough commonality and shared values that I believe in him and his leadership capability and will fight to promote him anyway I can. The fact that the alternatives are so frightening in their philosophies also compels me to be vocal in favour of Gowin.

Leopold Tyrmand (1920-1985) was a famous Polish writer known for his love for jazz, fun-loving lifestyle and strong anti-communism and Polish patriotism. He was born into an assimilated Jewish family in Warsaw. He survived the Second World War on fake papers giving him the identity of a Frenchman; he was active in patriotic Polish organisations during the war, and his novel Filip is a semi-autobiographical account of his wartime experiences. Tyrmand became one of the most popular post-war Polish writers, and his Diary 1954 (which will be published in English by Northwestern University Press in March 2014) and The Man with White Eyes have become canonical works. Tyrmand was a staff writer for the influential Catholic magazine Tygodnik Powszechny until it was closed by the government for three years in 1953 when it refused to publish an obituary of Stalin. He also became a populariser of jazz music in Poland, having founded the Jazz Jamboree Festival in Warsaw. In 1967, Tyrmand left Poland for the United States where he wrote for such magazines as the New Yorker and later worked for the conservative think-tank The Rockford Institute.

Matthew Tyrmand was born in 1981 in New York. His father Leopold Tyrmand originally intended to name him Mieczysław. Matthew Tyrmand studied Economics at the University of Chicago. He traded stocks on Wall Street for a decade, and now he has a consulting firm. In 2013, the Polish publisher Znak published his book Jestem Tyrmand, syn Leopolda(“I Am Tyrmand, the Son of Leopold”) about his discovery of Poland and of his father’s literary output as an adult. Matthew Tyrmand is currently working on investing in small and medium-size Polish businesses. He has started to write columns for Super Express, one of the top-selling Polish dailies. He has a twin sister Rebecca.

Filip Mazurczak is the Assistant Editor of New Eastern Europe. He studied history and Latin American literature at Creighton University and international relations at The George Washington University.