Unravelling the anti-immigrant discourse in Poland’s 2023 election campaign

In the digital age, with information flowing freely and narratives shaping perceptions, there is less and less hope of arriving at a point at which one objective truth prevails or even exists. This leaves us with the task of understanding discourses surrounding political events and processes. From that vantage point, one may look at the case of immigration to Poland and how it appeared in last year’s electoral campaign.

February 21, 2024 -

Maciej Makulski

-

Analysis

Former Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki (centre) together with the former Minister of the Interior Mariusz Kamiński and his deputy Maciej Wąsik inspecting the border fence with Belarus in June 2022. Photo: Kancelaria Prezesa Rady Ministrów / wikimedia.org

For most of the time after regaining its sovereignty from Soviet influence at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s, Poland remained a homogenous state with limited exposure to foreigners. Once the country introduced economic and political reforms and joined NATO and the EU, the country started down a path of growth that has made it one of the most successful countries of the former Eastern Bloc. This process has gradually transformed the country from one of economic emigration into a more and more attractive place for immigrants from different parts of the world, who ultimately seek to improve their economic and life chances. Major geopolitical events, among which the Russian aggression against Ukraine that started in 2014 and was transformed into a bloody war in 2022, caused an unprecedented influx of people from Ukraine coming to Poland either as economic migrants (mainly between 2014 and 2022) and refugees (after 2022). All of this means that Polish society now has to deal with a new period in relations with people of different cultures, which is causing new administrative and political challenges for state institutions.

Immigration to the EU has also been a long-term challenge for the whole bloc, which has caused divisions among member states for many years. The split was clearly visible in 2015 after Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel declared that she would welcome one million immigrants to Germany. This gesture was not appreciated nor followed by the majority of Central European member states, including Poland.

With the immigration issue high on the political agenda, both internally in Poland and at the EU level, it was inevitable that it would be a theme in the parliamentary election campaign of 2023. Tracing the patterns of how immigration was exploited and used across social media by different political groupings can offer evidence about the state of the debate regarding this topic in Poland. It can also help outline the challenges that lie ahead, since it is more than likely that immigration will be a key issue in upcoming electoral cycles, including the EU parliamentary election in June this year.

Immigration in public discourse on Facebook

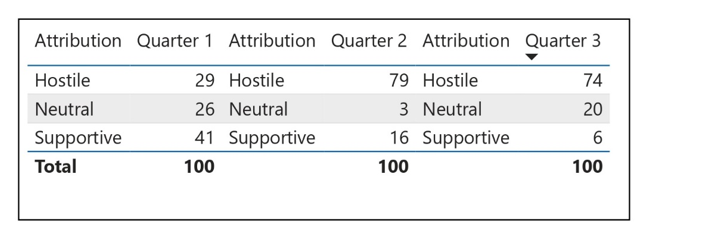

Immigration as a political theme during the campaign did not play a guiding role in the entire campaign but appeared during different events that caught the public attention more broadly. In early 2023 there was a relative silence on the topic and immigrants did not factor too often into the public discourse, neither in a positive or negative light. However, as the election campaign intensified, a significant shift occurred. Anti-immigrant sentiments gained momentum, overshadowing positive or neutral portrayals, especially in the second part of the year. This surge was not coincidental, as it mirrored the broader political context. This includes debates around the EU’s “Migration and Asylum Pact” and internal controversies such as the visa-selling scandal involving high-ranking officials from the Polish foreign ministry.

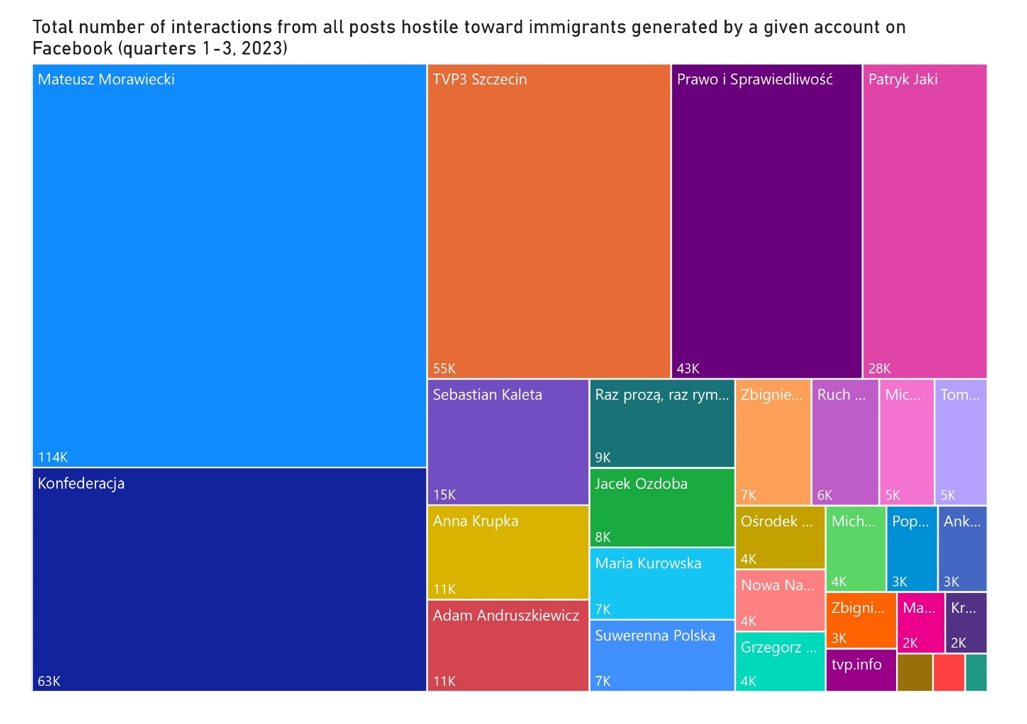

The ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party emerged as a significant contributor to the anti-immigrant discourse. Notably, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki’s account garnered the highest interactions, signaling a potent blend of political influence and messaging strategy. Meanwhile, opposition parties largely remained on the sidelines, perhaps recognizing the volatile nature of the immigration debate and its potential – negative for them – electoral implications.

The narrative’s evolution showcased tactical manoeuvres by political entities. While PiS and the far-right Confederation (Konfederacja) articulated distinct anti-immigrant stances, their underlying messages converged on the perceived threats posed by immigration, both culturally and economically. The “us-versus-them” dichotomy was palpable, with immigrants portrayed as outsiders undermining Polish values and stability.

While in opposition, Confederation tried to distinguish itself from the ruling party, combining its anti-immigrant message with a campaign highlighting what they perceived as the government’s hypocrisy. In their view, the government rhetorically presents itself as against immigration, yet at the same time issues a record number of work permits to foreigners, which the Confederation sees as tacit approval of immigration.

The issue of work permits for foreigners is worth noting in a slightly broader context. Indeed, since 2015, Poland has seen a significant upward trend in the number of work permits issued, which correlates with a growing demand for workers in the private sector. This is despite a concurrent negative long-term demographic trend for Poland. According to data from the Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy, in 2022 Poland issued a total of 365,490 work permits (in 2021 it was over 500,000) to foreigners, of which 23.28 per cent were Ukrainians and 11.39 per cent were citizens of India. From countries where Islam is the dominant religion, the most individuals arrived from Uzbekistan (9.13 per cent of all permits) Turkey (6.84), Bangladesh (3.7), Turkmenistan (3.26) and Indonesia (2.74). All the African countries included in the list had results below one per cent. Confederation, in its anti-immigration and anti-government message, did not indicate that the majority of work permits were granted to citizens of Ukraine (a total of 85,000 permits) and India (42,000), which did not in any way support the claim that Muslims or individuals from Africa constituted the majority in this group. As the campaign progressed, anti-immigrant content occupied less space in Confederation’s message. More important for this party was constructing a narrative around the Polish-Ukrainian grain dispute, based on which Confederation created one of its main election slogans – “no to social support for Ukrainians in Poland”.

The issue of immigration did not become one of the main points of dispute in the electoral campaign, among other reasons, because the opposition parties of that time (referred to by their supporters as the “democratic opposition”) did not speak too loudly on this issue. This probably stems from the belief that the general societal emotion regarding immigration aligns more closely with the positions advocated today by the right-wing in Poland. The securitization of the discourse surrounding immigration in Poland has deepened since the crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border. In 2021, Belarus started the process of pushing immigrants to cross the EU border (Poland, Lithuania and Latvia) causing a security crisis for all countries involved. Prior to that, the immigrants were brought to Belarus in a state-orchestrated process to eventually send people from Asia and Africa into the EU. The aim was to destabilize the security situation within the EU. As a response, Poland has strengthened its border with Belarus by building a fence along the border. Belarus continues to cause a crisis situation in the borderland today. Some immigrants have died whilst attempting to find a way to the EU through the woods and quagmires in the borderland, sparking a divisive debate in Polish society regarding the state’s response to the crisis.

Civic Coalition (Koalicja Obywatelska), the party now governing Poland, has not yet found a way to discuss immigrants in a different way. One exception to this is the leftist party Partia Razem (Together), which, while supporting the government, chose not to enter the ruling coalition. Its influence on political reality subsequently remains limited. Civic Coalition also tried to exploit the issue of work permits for foreigners similarly to Confederation, but without promoting an anti-immigrant stance as intensely as Confederation. However, in their case as well, they resorted to manipulating numbers related to people arriving from various countries. The main tactic of this party during the elections regarding immigrants was rather to silence the issue.

Yet, beyond the political strategy for the election campaign lies a deeper question: has the right captured and dominated the narrative about immigrants in Poland? Looking at it from the perspective of the 2023 election campaign, it seems so. It is possible that reversing this situation is currently impossible. This is significant because Poland is gearing up for future election cycles, including local and European Parliament elections in 2024. The issue of immigration will reappear in the public sphere, especially in the context of this second wider campaign. If undecided or centrist voters realize that the majority of political parties have started discussing immigration in the same manner as right-wing parties, they may be inclined to vote for these parties, seeing no difference in the message but recognizing the actual strength and effectiveness of right-wing discourse. Consequently, Poland may move closer to France and the Netherlands, where the rhetoric and discussion on regulating the immigration issue has tightened recently. . If other countries follow this trend, we might soon witness a closing-off of Europe to newcomers from other parts of the world.

This article is based on the report available here. It summarizes content monitoring on Facebook around the issue of immigrants in Poland during the first quarters of 2023. The report was conducted in collaboration with IRI’s Beacon Project.

Maciej Makulski is a contributing editor with New Eastern Europe.

Please support New Eastern Europe's crowdfunding campaign. Donate by clicking on the button below.