“Every Ukrainian is a hero”

Interview with Oleksandr Butkevych, the father of Maksym who collected the National Human Rights Award in the name of his son whose whereabouts are unknown. Interviewers: Claudia Bettiol and Francesco Brusa.

January 19, 2024 -

Claudia Bettiol

Francesco Brusa

Oleksandr Butkevych

-

Interviews

Photo: Volodimir Hanas wikimedia.org

“He’s critical of human rights violations, especially those on the side of the state, regardless of the place where they’re committed, be it Ukraine or abroad.”

– Denys Pilash, July 2022

Maksym Butkevych is a Ukrainian human rights defender and journalist, whose activity is focused on the protection of refugee rights. He is also the co-founder of the Human Rights Centre “Zmina” and Hromadske Radio. In 2020, following the protests against Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s government in Belarus, Maksym pledged to change the immigration regulations affecting repressed Belarusians who had fled to Ukraine.

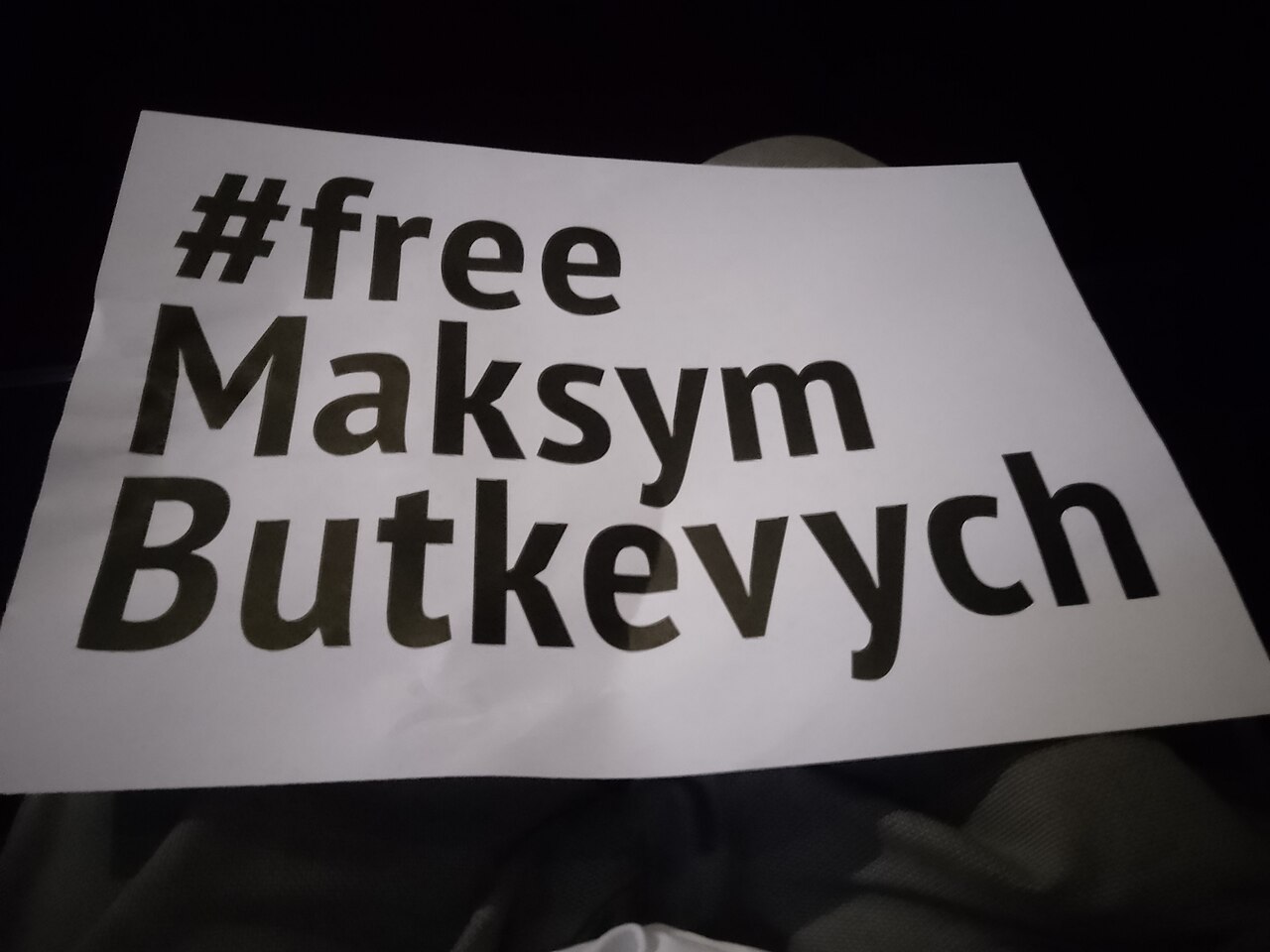

In March 2022, after the large-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, he announced his decision to join the Ukrainian army. A few months later, in July, it was reported that he had been captured as a prisoner by the Russian army near the settlements of Zolote and Hirske in the Luhansk region, and charged with crimes he never actually committed. He was unfairly condemned to 13 years of prison. As Amnesty International reports, after his capture, Maksym was the target of a smear campaign in the Russian media and denied a fair trial.

Since August 2023, Maksym’s relatives, friends and lawyers have been unable to obtain information about his status and whereabouts. Letters and parcels sent to Maksym at the pre-trial detention centre in Luhansk, controlled by the Russian authorities, are returned to the sender, and any request for information falls on deaf ears.

Last December, Maksym won the National Human Rights Award, a recognition of his personal contribution to the protection of human rights in Ukraine. The award was collected by his father, Oleksandr Butkevych, who we had the opportunity to interview.

CLAUDIA BETTIOL AND FRANCESCO BRUSA: Oleksandr, would you like to introduce yourself? What do you do, where do you come from and in what context did you grow up?

OLEKSANDR BUTKEVYCH: You ask me questions just because I am Maksym’s father. And that would be fair and enough, end of story. Because everything else is irrelevant, because it is not about me.

I can only briefly say that I am a Doctor of Sciences. I am a professor and chief researcher at the Institute of Electrodynamics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, and I teach part-time at the National Technical University of Ukraine, the “Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute”.

How did you react to Maksym’s decision to join the Ukrainian army?

My wife and I understood Maksym’s decision to defend his country, it could not have been otherwise. In 2014, when Russia began its military aggression, Maksym said it was his duty to defend Ukraine. The difference was that, back then, it was not a large-scale invasion. Maksym felt that he should do what he did best, which was to help people. He provided assistance (such as legal and material support) to internally displaced people (IDPs) from the occupied territories in Crimea and the Donbas region.

While in the ranks of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, on April 8th 2022, in a telephone interview with Tetyana Troshchynska on Hromadske Radio, Maksym explained: “I decided to join the army and defend the country, the city, everything that was important, even before the full-scale invasion. After February 24th, I had no other choice. We have been at war since 2014. Even then, I was thinking about the best place for me, the one where I could help the most. In 2014-15 I was not in the army, I was helping IDPs. It was important. My team managed to help many men and women. On the first day of the full-scale invasion, I packed up my belongings and went to the enlistment office. I knew I was not the best candidate: I had no combat experience and had not served before. I was told to wait for the call-up. It came in a week. During this time, I helped people evacuate and coordinated aid.”

Because Maksym was a devoted anti-militarist, many people did not understand his decision. Last year, we met with a group of Italian journalists, and one of them said he did not get it either, until he read Maksym’s article “Easter and Kalashnikov”. It was written while he was still serving in the Ukrainian army. Many answers to questions from colleagues and friends are found in this article.

“What they talk about though, apart from jokes and life stories, armaments and protection gear, is anger and the will to fight the invaders. This anger turns into open hatred with every next report about Russian troops shelling Ukrainian cities, mass graves discovered in formerly occupied areas, about raped, maimed and executed civilians, hostages taken and widespread looting committed by Russian soldiers. And there is too much evidence, too many witnesses and victims to even think of these reports as propaganda exercises. Dehumanisation is an unavoidable, and faithful, companion to every war; but sometimes it feels like occupiers do what they can so that Ukrainians could properly hate them.”

During the first moments of the invasion, were you able to spend some time together with your son?

Of course not! Maksym and I, as far as I remember, had many things to do that had to be quickly completed due to the outbreak of full-scale war. In the afternoon of “Day 1”, Maksym went to the enlistment office, where he was told to wait for the call-up. A few days later he was summoned and on March 4th he was already in the ranks of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Maksym is a well-known and respected person in Ukrainian society and in human rights and activist circles. From the moment your son was captured, were you able to count on the support and solidarity of people who knew him?

We knew that Maksym had many friends, but not that he had so many. He always put his friends’ problems and needs before his own. And his friends are happy to do the same for him today.

Maksym was among the Ukrainians who actively participated in campaigns for the release of Kremlin prisoners, including the well-known Crimean filmmaker Oleg Sentsov. Do you think this behaviour influenced the Kremlin’s attitude towards your son?

His actions were not limited to the release of Kremlin prisoners. Over the years, as a human rights activist, Maksym helped hundreds of people from Central Asia, Africa and later Russia and the Republic of Belarus. He helped them escape prosecution and imprisonment for religious, racial and gender discrimination, as well as gave assistance to many oppositionists, people in need and persecuted people in their countries (many of them were from Russia and Belarus).

In 2018, Maksym won the “Butkevič v. Russia” case at the European Court of Human Rights. The Russian Federal Security Services (FSB) seized the opportunity to take revenge on him and started to spread all sorts of nonsense in the Russian (and other) media about my son, calling him a fascist, a punisher, even a British spy (the last claim referring only to the fact that he had once collaborated with the BBC World Service in London, and because he had studied at and graduated from the University of Sussex).

In 1984, George Orwell could never have foreseen for the “Ministry of Truth” the high and unlimited level of absurd lies that Russian propaganda is using today. More absurd was also the charges against my son, made up by the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation. However, the so-called “judges” did not care, because they had instructions from above to be executed, despite the absence of any evidence of guilt and the presence of completely contradictory facts. They did not even allow the lawyer to see Maksym, nor did they inform anyone of the trial hearing date. On the contrary, they provided some FSB “lawyers” for his defence.

Do you have something to say to the people who are keeping your son in jail?

Yes, I have something to say to them but I won’t do it now because I don’t want to put my son in trouble. Guards, prisoner officers are just cogs in the enormous repressive system of the Russian Federation. A system in which tribunals are fake tribunals, accusations are fabricated and decisions are taken according to the instructions that come “from the top”, following indications by the secret services. The case regarding my son, which is in fact a completely false and fabricated case, is an example that confirms the widespread practices of the so-called “judiciary” and repressive system of the Russian Federation.

The award you just received was bestowed on Maksym because of his efforts in defending human rights and freedom and he finally decided to defend them by enrolling in the army. Do you think that Maksym can become a symbol for a part of Ukrainian society, given his profile and his political activism?

Yes, the National Human Rights Award that was bestowed on him following the “joint decision of all Ukrainian human rights associations” proves who Maksym really is: the opposite of what Russian propaganda is saying about him with its mockery. I think that my son has lived all his adult life with dignity by helping those who were in need, trying to concretely promote democracy, human rights and freedom in Ukraine. As I already mentioned, on the first day of the full-scale invasion he immediately went to the enlistment office, and he did so to continue to defend those values of democracy, human rights and freedom to which he dedicated his life before the war. He knew that he had to protect his country because he was aware that Russia would have destroyed all of this. Russia doesn’t want an independent Ukraine nor human rights or freedom.

In a similar way, many human rights activists, journalists, engineers, singers, people with any kind of job or education, of different ages and religious beliefs volunteered to defend the country. Amid this war, many Ukrainians died in battle while defending their homeland and many others are still fighting as heroes. Each one of them is indeed a hero and can be a symbol of the invincibility of Ukraine. Nowadays, every soldier of the Armed Forces of Ukraine is a symbol and Ukrainian society has a great degree of trust and respect towards them.

Last November it was the tenth anniversary of the Maidan protests. After ten years, Ukraine is in the process of joining the European Union, a process that at the time of Maidan was blocked by Yanukovych, while now this goal looks to be almost achieved by President Zelenskyy. As a Ukrainian citizen, what does this European integration represent for you?

For a long time – even after Russia violated the international agreements on the territorial integrity of Ukraine with the armed occupation of Crimea in 2014 – the European Union remained kind of “blind” to what was happening. It decided only to express some “preoccupation” regarding the unfolding events but it didn’t explicitly condemn the aggressor or it didn’t take any real action. The war in Europe unleashed by Russia was “somewhere far away” and European countries put their economic interests above anything else. Moreover, it is clear that the decision-making process in the European Union is slow and flawed as we see with Orban or other pro-Russian leaders, who can block or slow down any decision. So I think some changes on this matter are needed.

At the same time, integration in the European Union represents for Ukraine the only reliable way to move away from the Soviet past and its aggressive and chauvinistic neighbour, all the while embarking on the path of the democratic development of a state that respects human rights and freedoms. The process of joining the EU might not be as fast as we want, but it’s important that we have already started on that road.

How is Ukrainian society reacting to the war? Do you see any significant change? What are your biggest fears and your biggest hopes for the future?

In my opinion, the biggest changes in Ukrainian society amidst the current war are linked to the increasing awareness that we are confronting a “global evil”: the “Russian empire” and its fascist ideology. Before 2014, and sometimes even before 2022, part of the Ukrainian society didn’t really think about the aggressive intentions of the Kremlin, because some people had personal relations in Russia. But the massacres in Bucha, Irpin, Borodyanka, Mariupol and other Ukrainian cities and villages, as well as the daily missile strikes and subsequent civilian deaths, dispelled the illusion about any peaceful attitude from Russia.

As for my fears, I’m afraid about the economic impoverishment of the country due to the war and about the loss of human lives. We are indeed losing our best people (according to many standards).

For a long time, the propagandists of the Kremlin have tried to brainwash people by saying that Russia is waging war not against Ukraine but rather against NATO troops deployed on Ukrainian territories. So Russia is merely defending the “Russian world” (russkiy mir), which is everywhere, in every place and country where there are Russians who need to be protected from someone or something. And it doesn’t matter if these Russians are not actually in need of protection or if they even exist or not. The Russian world has to be exported (also with missiles and tanks) in order to be protected. This is the kind of primitive pattern employed by Russian propaganda.

The fact that Russia has broken every international law is upsetting. And yet, the aggressor with the biggest amount of blood on its hands of our time still sits in the Security Council of the United Nations. It’s a paradox, it’s an insult to common sense, and to the many thousands of people who have been murdered or are now mutilated because of Russian aggression.

It’s disturbing that someone who should be in front of the court in The Hague has been invited to the G20 meeting; that media in many countries just report pro-Russian narratives calling for the ending or the restriction of military assistance to Ukraine; that leaders of some countries don’t follow the very democratic principles and values they promised to follow when they were asking the people for their votes and support, with the pretext of some “formal rules”. They continue to claim their commitment to democracy while behind the curtain they act otherwise, they have a double standard. The relatives of the members of the Russian government who started a bloody war of aggression keep on living their luxury life in Europe thanks to “democratic principles” (that is to say they are not subjected to any sanction or restriction), while Russian propagandists on television make fun of democratic principles and laws by which people of other European countries live, threatening to burn their capitals and major cities down and leave them in “nuclear ashes”. It’s worrying that economic sanctions against Russia are not effective, since it is possible to circumvent them in multiple ways and Russia is taking advantage of that. Finally, it’s deplorable that many companies (even European and American companies) are violating the sanctions while they know perfectly who is benefiting from that.

Personally, I hope for active support from European countries and especially by the US that will help us to resist and to win this war. I would like to see a more determined support without hesitations or double standards regarding Ukraine. And, of course, I hope that there will be a swap of prisoners soon so that I could see my son coming back home together with other Ukrainian prisoners. I would like to see an “all for all” swap as soon as possible.

I also hope that as a result of the war, Ukraine will become a cohesive and strong state, with three branches of government, professional, responsible and with high moral standards. A state with an advanced economy and with a modern and well-equipped army able to defend the country from any aggression. I hope that any obstacle to the paths towards democracy will disappear forever and that any further development of the institutions of the country will happen according to the principles of human rights and freedom.

This interview was originally published in Italian on the Meridiano 13 website and social media channels.

Oleksandr Butkevych is a professor and Chief Researcher at the Institute of Electrodynamics of the National Academy of Sciences in Ukraine and father of human rights defender Maksym.

Claudia Bettiol is an Italian translator and journalist. She has been living in Ukraine since 2017 and has been the Kyiv correspondent for Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso since 2019. She is also the co-founder of the media project Meridiano 13, in which she collaborates with MicroMega and other Italian outlets. In 2022, she translated from Ukrainian into Italian the reportage “Our others” by Olesja Jaremčuk, published by Bottega Errante.

Francesco Brusa is an editor at Dinamopress, a freelance journalist and theatre critic. He collaborates with several magazines and various online sites, mainly dealing with political and social developments in the Eastern European and Anatolian area.

Please support New Eastern Europe's crowdfunding campaign. Donate by clicking on the button below.