Feeling history, 70 years on

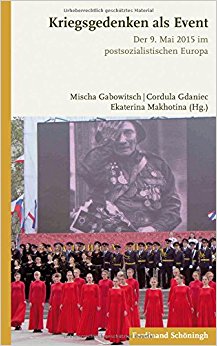

A review of Kriegsgedenken als Event. Der 9. Mai 2015 im postsozialistischen Europa (War memory as an event. May 9th 2015 in post-socialist Europe). Edited by: Mischa Gabowitsch, Cordula Gdaniec, and Ekaterina Makhotina. Publisher: Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn, Germany, 2017.

May 9, 2018 -

Paul Toetzke

-

Books and ReviewsHot TopicsIssue #5/2017Magazine

On May 9th 1945 the Soviet leader Josef Stalin announced: “Comrades! The Great Patriotic War has ended in our complete victory. The period of war in Europe is over. The period of peaceful development has begun. I congratulate you upon victory, my dear men and women compatriots!” During the late evening of May 8th the German authorities had ratified unconditional surrender and thus sealed the end of the Second World War in Europe. Due to the time difference, it was already May 9th in Moscow, and that date became the official date of Victory Day in the Soviet Union.

No other country has ever had so many people involved in military action as the Soviet Union during the Second World War. Today the so-called Great Patriotic War remains one of the main pillars of post-Soviet identity – a symbol used to emphasise the importance of the co-operation between the former Socialist states and to commemorate the deeds of the Red Army. In today’s Russia the cult of the Great Patriotic War and the defeat of Nazi Germany remain omnipresent in society. New publications and movie productions aim to keep this myth alive, while the line between fact and fiction becomes more blurred.

Immortal regiment

May 9th marks the zenith of this memory, and since 1965 it has become the most important national holiday in Russia and in several other post-Soviet states. Today it is the ultimate celebration of the historical significance of the Soviet Union and the Red Army. Military parades – especially the Moscow parade – civil marches and memorial commemorations in schools are an indispensable part of this holiday in Russia and abroad. What seems to be primarily a demonstration of power is an essential, if not the most essential, subject of the post-Soviet politics of memory, which people from different states can identify. For others, it is simply a day to get together for drinks and food, while remembering the legendary actions of their ancestors. In other words, May 9th and its symbolism has become an occasion for the young and old and something that has developed its own spirit beyond the state organised celebrations.

In 2012 a new movement called “The Immortal Regiment” emerged and has become an inherent part of the Victory Day Celebrations. Participants in this march hold up portraits and photos of their ancestors who fought in the Second World War. It helps bring their personal history to the symbolic meaning behind the day. During the 70th anniversary of Victory Day in Russia, Vladimir Putin joined the march with a portrait of his father. This collective remembrance has so far been established in 15 other countries. It is evidence of how grassroots memorial practices and state-led events overlap during the May 9th celebrations.

How has May 9th and its meaning shaped public spaces around Europe? What are the main differences between the celebrations in different countries? To what extent are the they controlled by state authorities? A recent book published in Germany, Kriegsgedenken als Event (War memory as an event), tries to answer these questions. It is based on research carried out during the 70th anniversary of Victory Day in Belarus, Germany, Estonia, Russia and Ukraine. On May 9th 2015 the authors and field researchers conducted around 500 interviews and collected more than 2,000 press articles. The observations are supported by photos and maps. In contrast to earlier research, the focus of the book is performative memory and the practical realisation of the festivities in each of the countries.

The real value of the book, however, lies in its depiction of the Soviet heritage and the way different post-socialists states are dealing with it. It notes the particularities of the five chosen countries and provides a deeper understanding of their present situation. Especially interesting in this regard are the observations from Ukraine, which offers a detailed insight into a society that is affected by war.

Divided and disrupted

The interviews reveal the deep cut and inner conflict of the nation. Moreover, observations from different places throughout Ukraine show a variety of public engagements in historical memory, but also document its changing dynamics in politically tense times. The festivities in Donetsk, for instance, resemble the ones in Russia, while the celebrations in Kyiv are much more based on Ukrainian national symbols. The book gives a background on how the government under President Petro Poroshenko has tried to shift the focus of the celebrations away from its Soviet-shaped meaning and adapt it to the country’s current national and European orientation. In Odesa, on the other hand, the authors face a completely divided population. One visitor, wearing the black and orange St. George Ribbon, is quoted saying: “This is a symbol of victory that has always existed. It expresses honour, victory and heroism. This is a symbol that you cannot just abandon. This is not possible.”

The book also shows a photo of a girl in Simferopol, in Crimea, holding up a self-made sign saying: “Thank you, grandpa, for victory! Thank you, Putin, for Crimea!” The observations from Ukraine highlight the difficult future the country faces and the difficulty of finding the right balance between a return to its national, independent roots and the incorporation of its Soviet past. Furthermore, the interviews reveal how strongly people in Ukraine relate their visit of the occasion to the current war in the region. For many, the fact that they experience the reality of war makes this day even more sacred.

The May 9th celebrations in Russia are portrayed as a cult that is more like a civil religion of the whole country than a state-organised event. Moreover, they depict a place in which regional initiatives do not necessarily compete, but rather complement each other. Oftentimes these impulses come from small towns and villages that contribute in their own, personal way. One man in Smolensk, for instance, explains why there are no flags during the March of the Immortal Regiment: “The day of victory should be free from politics and party ideology. This day should unite society, not divide it.”

However, contrary to the assumption of this man, the book shows that in almost all of the five countries the occasion is clearly used for political purposes. This is particularly evident in Belarus, where the celebrations are probably the most state-controlled of the five researched countries. According to observations, there is no mix of official and non-official events. Instead, the symbol of the Great Patriotic War is used for political mobilisation and consolidation of loyalty towards Soviet tradition.

Interpretation and entertainment

While the research in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine focuses more on the practical realisation of remembrance, the research from Estonia and Germany takes a closer look at who is taking part. This question of identity-building seems to be more interesting in regards to the fact that in both cases Russian-speaking groups are a minority – even if a large one, as in the case of Estonia. The authors argue that in both cases specific communities of shared memory have emerged that create their own collective identity and May 9th marks an important event to express this shared identity. Moreover, the book analyses the relations between the post-Soviet and European historical interpretation and the question of sovereignty of interpretation – a topic that is extremely relevant, especially when looking at the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

The May 9th commemorations, 70 years after the end of the Second World War, are as important as ever. War memory as an event illustrates that the significance of the celebration lies in the occasion itself. Despite the different historical interpretations between the different post-socialist states, May 9th is also a day for fun and entertainment. In all the five countries, people present their personal relation to the day and create a space for experiencing history. Hence, the experience itself, rather than the actual historical reality of the events, is the focus.

War memory as an event presents these different dynamics in a detailed and vivid way. The interviews with participants and photos present a great insight into each country’s relation to May 9th and its Soviet past. In the end, the reader is left wondering about the consequences of an “eventisation” of history that is more about feeling history than dispassionately scrutinising it.

Paul Toetzke is a freelance journalist and Masters student of East European Studies at the Freie University in Berlin.

This review originally appeared in issue 5/2017. Click here to subscribe to NEE.

This review originally appeared in issue 5/2017. Click here to subscribe to NEE.