The Romanians Don’t Fit into Any of Europe’s Tribes

An interview with famed Romanian-American poet Andrei Codrescu, Professor Emeritus of English at Louisiana State University. Interviewer: Filip Mazurczak

January 31, 2014 -

Filip Mazurczak

-

Interviews

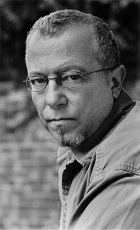

Photo: Marion Ettlinger

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe. New Eastern Europe will regularly feature texts on this topic, the first being Filip Mazurczak’s interview with the famous Romanian-American poet Andrei Codrescu, who was ABC News’ correspondent in Bucharest in 1989, on his native country’s place in today’s Europe.

FILIP MAZURCZAK: A quarter of a century after the collapse of communism in Romania, how do you see the progress your native country has made? Is Romania, today a member of NATO and the EU, a success story, or does its relatively high poverty level mean that it has not realised its full potential?

ANDREI CODRESCU: Romania might have, potentially, been a much better contributor to the world it is reluctantly joining. Unfortunately, its communist legacy didn’t end with the assassination of the Ceaușescus by their inner circle. That circle divided the corpse of the state between themselves like hungry buzzards, and now their children hold political power. These children have already mutated into something better, though: they were nourished on communist milk and nationalist kitsch, but many of them went to school in the United States and England. In a future generation, the economic and cultural stupidities of the communist dictatorship will be forgotten. Instead, the stupidities of capitalism and crass ignorance will be assiduously practiced. This is a pattern common to many ex-commie fiefdoms. It is also possible that Russia might yet exert enough petrol gravity to draw Romania back within its sphere of influence, but never to the extent that the USSR had. The gravest problem now is brain drain and the scale of political patronage. The brightest of the young leave for better jobs in the West, and corruption is still taken for granted. Still, Romania is rich in talent and resources: its best days are ahead.

In his book Uncivil Society published in 2009, Princeton University historian Stephen Kotkin wrote that the democratic opposition in communist Romania was very weak and very small. Would you agree with this statement and, if so, how would you explain the events that took place on Christmas in 1989 which led to the execution of Romania’s communist leader Nicolas Ceaușescu and his wife?

Pre-1989 Romanians knew little of democracy. They were all opposed to the regime because it didn’t provide basic necessities. The West for them possessed something called “freedom” and “food”, which were “capitalist” miracles. The regime had few ideological opponents because the study of Western democracies and economies was either non-existent or viewed from a Marxist perspective. Few people foresaw the civic responsibilities that came with voting, public debate, freedom of speech, minority rights, a healthy legal system and an elected legislature. The opposition that emerged after 1989 was a ragtag group of former political prisoners and a few ancients who had belonged to pre-communist liberal parties. Romania went directly from a fascist dictatorship to a communist democracy, with only a brief but loud and colourful democracy from 1918 until 1930. No wonder, then, that the communist nomenklatura and its children found it so easy to pluck. As I said above, the Ceaușescus were killed by their henchmen; the “revolution” was a classic coup d’etat.

From all countries in the former Soviet Bloc, Romania was the only country where the overthrow of communism happened violently. Why?

This was because Romanians are theatrical. They made sure that the operetta of the “revolution” produced real bodies for its effects. There was also a gang fight between units of Securitate (the secret police) and the army. The Romanian “revolution” was conducted mainly from the state television studios, and December 1989 was also the anniversary of the French Revolution. Our talented producers, conscious of their medium, produced as many Delacroix-type pastiches as possible (with real victims in the set design). Modern Romania was always Francophile.

Arguably, one of the biggest successes of Romania after 1989 is the flourishing of its film industry. Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days won the Palm d’Or at Cannes in 2007, and several other Romanian films have been globally successful. Yet these are not films about the beauty of the Carpathian Mountains, but about the gritty, ugly days of communism and the aftermath. Why is this so interesting to Western audiences?

In the West, we were fed the black-and-white propaganda of the bipolar world, so the “world behind the Curtain” was a mystery. Romania was an even greater mystery because its ambassadors, Dracula, Nadia Comăneci and Eugène Ionesco, were great sexual titillators of our jaded consumer society. The vampire, the gymnast and the intellectual comedian fascinated the West. It was a real surprise when Mungiu and other young story tellers started telling the true, grim but human-scaled stories of their parents’ miserable world. The West realised (some people did, anyway) that humans lived over there, too, not just mythical ogres. What a disappointment!

The Romanians are descended from Romans (Ovid lived in what is today Romania) and speak a Romance language and the connections with the French culture are quite strong; lest we mention great Romanian intellectuals, such as Eugène Ionesco, who were expatriates in France. At the same time, Romania adheres to Orthodoxy, rather than Western Christianity, and the Romanian language was written in the Cyrillic alphabet until the 19th century. Where does Romania fit in in terms of civilisation, is it Eastern, Western or something in between?

One of the glories of Romania is that it doesn’t have to fit in any of Europe’s neat religious-orthographic tribes. The Romanians have benefited from the (often violent) meeting of cultures, including those of the ten invasions by tribes from Asia. A Latin people in a Slav sea, genetically worked-over by Goths, Vizigoths, Mongols and Khazarsand Avars, Romanians are also situated in Balkan Thrace, the birthplaces of Orpheus and Pan. As the post-Roman Europe settled into its identity wars, Romanians sought instead a cultural space that could make their poli-inheritance liveable. It was by no means a peaceful process, but a Europe that is now groping for a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural modus vivendi has a lot to learn from a country whose very history is that practice. Part of the reason why Romanian intellectuals can establish themselves quickly in France or the US is that they possess an organ for sensing the benefits of difference.

In 1989, you returned to your native Romania to cover the overthrow of communism for the American media, including National Public Radio and ABC News. How did you feel witnessing this in Romania? Were you excited at the prospects of freedom for your homeland, or were you anxious about Romania’s uncertain post-communist future?

Well, all of it and more. I was excited to again find the sounds, smells and places of my childhood and adolescence. I used all my senses to report something that wasn’t exactly journalism, but more of a sensorial rebirth. I was also anxious and aware that it was a fluid situation and that maybe the bad guys could win. (I didn’t know then, for at least three months, that there was only one bad guy, Ceaușescu, and that everyone else was a “revolutionary” good guy). I was (am) also worried by the insanity of the nationalist sickness that the communists cultivated just as the fascists had. “Nationalism” is all the more ironic in Romania given the multiple sources of the nation I mentioned above. Unfortunately, nationalism is a European disease of long standing and is the best outlet for bloodlust, just ahead of football.

Andrei Codrescu was born in Romania in 1946. At the age of 20, he immigrated to the United States, where he has become a noted poet and was a professor emeritus of English at Louisiana State University. In 1989, he returned to his native Romania to cover the anti-communist revolution there for National Public Radio and ABC News; this experience was the basis for his book The Hole in the Flag: an Exile’s Story of Return and Revolution. His humorous 1993 documentary Road Scholar, chronicling his cross-country trip across the United States, has become a cult classic. A laureate of the Ovid Prize, Codrescu’s most recent volume of poetry is So Recently Rent a World: New and Selected Poems, 1968-2012. He is the editor and founder of the prestigious online journal Exquisite Corpse.

Filip Mazurczak is the Assistant Editor of New Eastern Europe. He studied history and Latin American literature at Creighton University and international relations at The George Washington University.