Mysteries of “Great Russian literature”

The expression “Great Russian literature” remains a ubiquitous phrase in discussions surrounding Russia’s literary output. In spite of this, history shows that this phrase possesses a key political aspect that is essential to understanding the Kremlin’s hybrid war today.

October 21, 2022 -

Tomasz Kamusella

-

Articles and Commentary

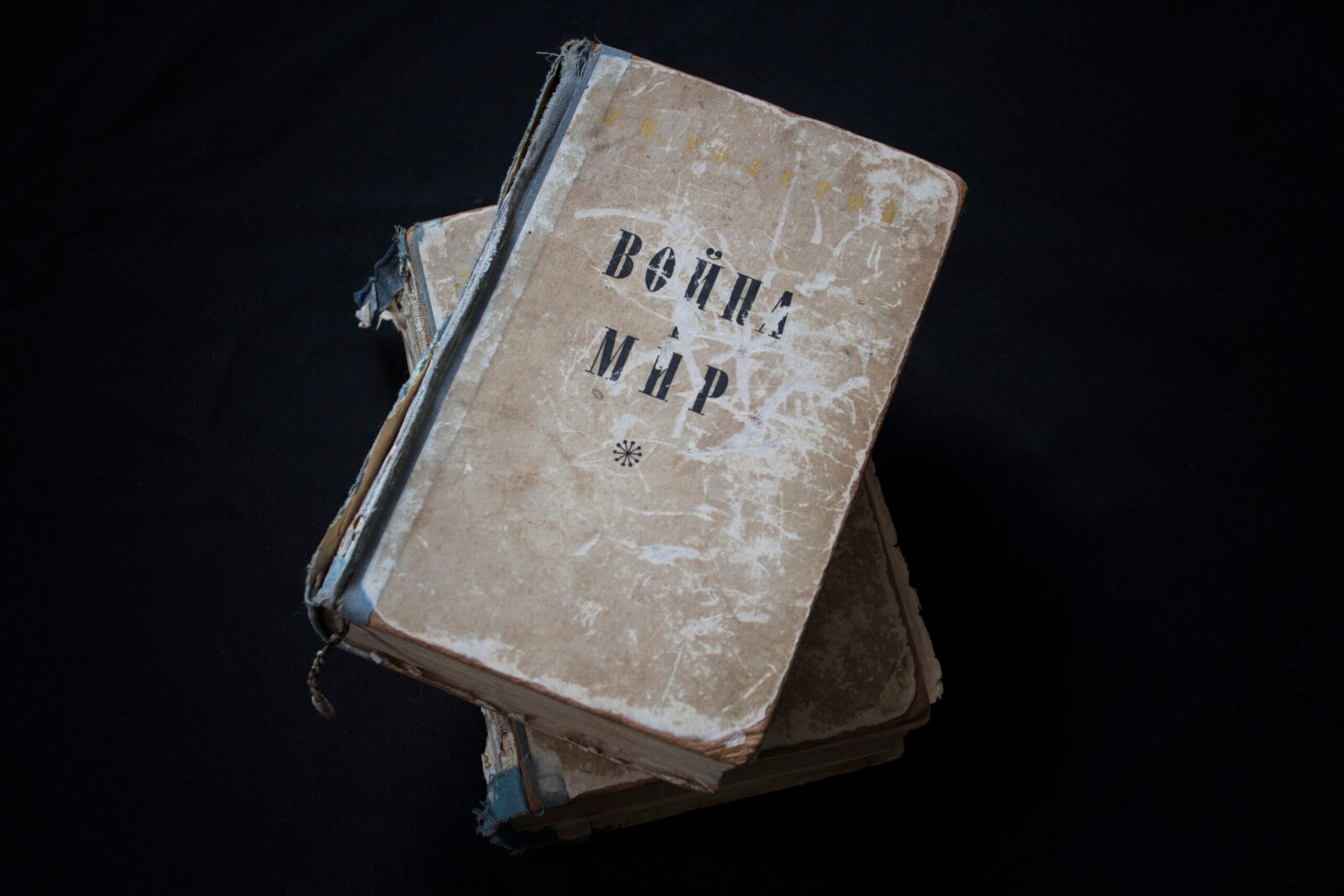

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1869). Source: Lena Philip / Shutterstock.

In English-language publications the set phrase “great Russian literature” pops up quite frequently when Russian culture or the Kremlin’s current abuse of this culture for political ends are discussed. Curiously, no thought is given to the fact that no set phrases of this type exist for talking about English, French or German literature. Yet, at present this unthinking use of the ossified expression “great Russian literature” in the West facilitates Moscow’s weaponisation of culture. Hence, the urgent need arises to reflect on the origins of this strange expression, which would help wean western commentators off it in favour of freer and evidence-based thinking.

Russian imperialism continued

To the whole world’s profound shock, on February 24th 2022 Russia launched a full-scale invasion of peaceful Ukraine. This unprovoked war is a throwback to Europe’s imperial past. Until the mid-20th century, it was deemed “normal” that a state larger than its neighbours in demographic, territorial and military terms may choose to conquer nearby states or their regions. In the early modern period, such a move would be “justified” through the “necessity” to Christianise “pagans” (or peoples who professed non-scriptural and non-monotheistic religions) and “infidels” (that is, Muslims and Jews), or to spread the “right form” of Christianity, be it Catholicism, Lutheranism or Orthodoxy. After the end of the religious wars, social Darwinism and geopolitics took over as “modern justifications” of imperial conquests. In this line of thinking, empires were “better fit” for survival at the expense of weaker and smaller polities.

With the Helsinki Final Act signed by the West and the Soviet bloc countries in 1975, the imperial logic of doing politics in Europe was laid to rest. The largely parallel processes of European integration and NATO enlargement are steeped in respect for all European states regardless of size. This respect, alongside the Helsinki principle of the inviolability of borders in Europe, became the cornerstone of peace and stability on the Old Continent in the wake of the fall of communism and the breakups of the ethnoterritorial federations of the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Yet, the freshly post-Soviet Russian Federation almost immediately began to undermine the established order in the name of an increasingly resurgent Russian imperialism.

First, Moscow quietly tried its hand at this new imperialism by carving out Transnistria from Moldova in the course of the 1992 war. Next came the not so underhanded genocidal-scale suppression of independent Ichkeria during the two Chechen wars (1994-96, 1999-2000). At that time, the West still harboured a hope that Russia would become an outsized but largely “normal European country”. Early signs of resurgent Russian imperialism were dismissed as political “phantom pains” of the suddenly vanished Soviet empire. In Brussels or Washington politicians were not eager to listen to Moldovan or Ichkerian complaints to the contrary. Instead, Russian officials and figures of culture were lionised in western capitals. Not incidentally, they enhanced their warm reception in Paris, London, Rome or New York through billions of petrodollars generated by new Russia’s “economic miracle”. Getting acquainted with a Russian oligarch became a much sought sign of distinction. Furthermore, in 2001, to the Chechens’ dismay, the US welcomed Russia as a trusted ally into the “War on Terror”.

Meanwhile, reunited Germany reimagined its Cold War Ostpolitik as Wandel durch Handel (“change through commerce”). The widespread belief was that oil and gas-rich Russia would gradually turn democratic through economic and technological entanglement with the West. In return, Berlin gained preferential access to cheap Russian energy, which helped to make Germany a world-leading export economy. The system worked just fine for a generation during the three post-communist decades. Or did it?

Unabashedly, Russia attacked Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014. The Kremlin seized almost a fifth of Georgian territory, annexed Ukraine’s Crimea and took effective control of easternmost Ukraine. In the last area, to destabilise Ukraine, Russia fuelled a low-intensity border war between 2014 and 2022. Beginning in 2015, Moscow intervened in the Syrian Civil War on the side of the ruling dictator. The Russian army perfected there their novel tactics of rapidly levelling entire cities, originally developed during the Chechen wars.

Despite this unrepentant course, after a five-year suspension following the Kremlin’s annexation of Crimea, Russian parliamentarians were permitted to rejoin the Assembly of the Council of Europe in 2019 despite Kyiv’s protests. Less than three years later, in 2022, their country used this “method” of destroying cities on an unprecedented scale to beat the Ukrainians into submission. Quite a late wake-up call for the short-sighted West, who at long last began to notice that after all something has been amiss in its cozy relationship with the kleptocratic and murderous Russia of today.

“Great Russian literature”

Apart from all the shady billions of dollars for the western likes of Gerhard Schröder or François Fillon, the Kremlin has successfully corrupted and “softened” the West with the widespread and equally widely accepted stereotype of “great Russian culture”. Russia has excelled at financing music events and arts initiatives across Europe and North America. This was especially welcome following the austerity measures that struck in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

In this manner, leading Russian figures of culture have been introduced into the public consciousness across the West. By showing openly their unwavering and unthinking loyalty to Moscow, they act as significant agents of influence to confuse public opinion in Europe and North America. Such pro-Kremlin musicians, painters, actors, directors, conductors, or writers give credence to Russian authoritarianism and imperialism as a “valid alternative” to democracy and human rights. On top of that, beginning in 2007, a dense network of Russkiy Mir (“Russian World”) Foundation centres were created across the West. Ostensibly, like the British Council, these centres are to teach and promote Russian language and culture. In reality, non-transparent financing and toeing Moscow’s line make these centres into a key channel of Russian propaganda and influence. Unfortunately, to this day the globe’s Russkiy Mir branches remain “legitimate”, despite Russia’s ongoing total war on Ukraine.

After all, there is no question over whether or not the punitive western sanctions aimed at the Russian economy and officials should “cancel” Russian culture. That would be too much of a reaction. Really? Is the immersive experience of Leo Tolstoy or Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novels enough for the West to ignore the ugly reality of Russian neo-imperialism? Will it make Europeans and Americans conveniently overlook the Russian brutality that has cost the lives of tens of thousands of Ukrainians and has displaced over 14 million and counting?

Western moderates emphasise that no war – however unjustified – will ever diminish “great Russian literature”, which cannot be “cancelled”. Yet, no one seems to reflect on why the English phrase “great Russian literature” functions as a well-established collocation that garners almost 80,000 hits on Google. On the other hand, the expressions “great English literature”, “great French literature”, or “great German literature” do not function as set phrases or collocations. Does this mean that English, French and German literatures are inferior to their Russian counterpart? Were Shakespeare, Molière or Goethe lesser poets than Russia’s Pushkin, who still continues to be relatively unknown on the global literary stage?

Changing names of Russian

The rise of the English collocation “great Russian literature” has nothing to do with this literature’s inherent qualities or cultural influence. As typical in such cases, vagaries of history were at play here. An explanation lies with the Russian-language name of the Russian language, which changed twice between the early 19th and early 20th centuries. But the story was consigned to oblivion in Russia itself and lost in translation into English. As a result, nowadays in the West, scholars and even hard-hitting commentators on matters Russian parrot this collocation “great Russian literature” without giving it any thought. As though it were obvious that Russian literature must be “naturally” great. Unwittingly, all of us who unreflectively repeat this set phrase contribute for free to the Kremlin’s arsenal of “soft power” employed for conducting hybrid warfare, which kills for real. Beware!

From the historical perspective, Russian is a mixture of Church Slavonic (Slavenski “Slavic”) and the Muscovian vernacular, or the Slavic dialect of Moscow. It was the Russian polymath Mikhail Lomonosov, who proposed such a formula in the mid-18th century. In 1755, his western-style grammar of Russian written in Russian came off the press. In Russian Lomonosov referred to this new language as Rossiiskii. He derived this designation from the name of the Russian Empire (Rossiiskaia Imperiia), as proclaimed by Tsar Peter the Great in 1721. Both the empire and its language were then new projects that came along in quick succession, separated by as few as three decades. It was also another conscious act of emulating the West. After all, Spanish scholar Antonio de Nebrija, in the dedication to Queen Isabella I of Castile in his Gramática de la lengua castellana (1492), famously proposed that “language has always been the perfect instrument of empire.”

The French-speaking Russian ruling elite at the imperial court at St. Petersburg decided that a future Russian should be closely modelled on the West’s then most prestigious language, namely, French. At that time, French was the sociolect of all Europe’s nobility. In 1762, the fourth edition of the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française (Dictionary of the French Academy) was published in Paris. In Russia, two decades later, this reference was duly translated into Russian, yielding the Polnoi frantsuzkoi i rossiiskoi leksikon’’ / Dictionnaire complet françois et russe (Complete French-Russian Dictionary, 1786). The new language’s name, Rossiiskii, remained the same as proposed by Lomonosov.

This lexicographic achievement encouraged the Russian Academy to produce an authoritative six-volume monolingual dictionary called the Slovar’ Akademii Rossiiskoi (Dictionary of the Russian Academy), which appeared between 1789 and 1794. Interestingly, the name of the standardised language is not explicitly mentioned either in the dictionary’s title or introduction. But afterward Russian, officially known as Rossiiskii, became the main official language of the Russian Empire, especially in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars. Following the defeat of the French invasion of Russia (1812), the ethnically Russian and Orthodox segment of Russia’s nobles consciously limited their day-to-day use of French.

However, the language’s Russian-language name was quite abruptly altered between the mid-1830s and mid-1840s, from Rossiiskii to Russkii. The root cause of this change was the 1830-31 anti-Russian uprising staged by the Polish-Lithuanian nobility, who wanted to re-establish their Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania as an independent country. In the late 18th century, Russia, Prussia and the Habsburgs had partitioned this realm. The Russian tsar gained as much as four-fifths of the Polish-Lithuanian territory. These lands were then the best developed in the Russian Empire. As such, they were designated to function as the socio-economic basis for the empire’s modernisation through westernisation. To this end, Polish was retained across these vast territories as the official language. Russia’s then largest university in Wilno (Vilnius) employed Polish as its language of instruction. This institution produced two-thirds of all the empire’s university graduates, and was twice the size of Oxford University in terms of students enrolled. But because of the uprising the tsar decreed its permanent closure in 1832.

In 1833, the shock of the aforementioned Polish-Lithuanian uprising prompted Russian Minister of Education Sergey Uvarov to come up with the political slogan “Orthodoxy, Autocracy and Nationality” (Pravoslavnaia Vera, Samoderzhavie i Narodnost’). This slogan’s aspiration to confessional and linguistic homogeneity under the tsar’s absolute rule, supposedly conferred on him by God, became the empire’s “modern” ideology. It drew heavily on the idea of a shared language (that is, “nationality”) as the definition of the nation or body politic. Originally, it was the poet and anti-Napoleonic activist Ernst Moritz Arndt who inserted this formulation into his 1813 poem “Was ist des Deutschen Vaterland?” (What is the Fatherland of the Germans?). His answer to this then hotly debated political dilemma was that such a German nation-state in waiting should extend “where the German tongue sounds” (So weit die deutsche Zunge klingt). In all likelihood, Arndt composed this poem in 1812, when he stayed in St. Petersburg, helping the Prussians with the shaping of the Prusso-Russian coalition that finally defeated Napoleon.

After 1833, in a coordinated fashion, St. Petersburg imposed either Orthodox Christianity or the Russian language on conquered peoples to give a stronger ideological coherence (understood as cultural homogeneity) to the empire. In most cases it proved too difficult to impose both religion and language. And with time, the practice showed that linguistic homogenisation was less contentious than its confessional counterpart. Hence, following their defeated uprising of 1830-31, the Polish-Lithuanian nobility were allowed to keep their Catholic religion. Yet, Polish as the official language of their historic lands was replaced with Russian. This change was supported by a legal provision from the 16th-century Lithuanian Statute. Until 1840 this law book remained the basis of law in most Polish-Lithuanian lands under Russian rule. The statute proclaimed that these lands’ official language must be Ruski (Ruthenian).

Yet, as readily visible from the obvious difference in the spelling and pronunciation of its name, Ruski was not Rossiiskii, as Russian was known then. Ruthenian and Russian were two different and separate languages. Equating both for the sake of replacing Polish with Russian as the administrative language of the former Polish-Lithuanian lands was a political ploy. Yet, it required the aforementioned change in the Russian-language name of the Russian language from Rossiiskii to Russkii. Otherwise, leaning on the Lithuanian Statute as the legal basis for changing the region’s official language would have been unbelievable, at least, for the Polish-Lithuanian noble elite. Despite the defeat on the battlefield, they remained a substantial political force to be reckoned with, because they accounted for as many as two-thirds of all the Russian Empire’s nobles.

The irony is that the original Ruski–Ruthenian of the Lithuanian Statute functioned as the official language in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania between the 13th and late 17th centuries. That is long before Lomonosov even proposed how Russian could be codified as a “modern” (that is, western-style) language. Ruthenian was the first ever Slavic vernacular in regular written use. From Ruthenian today’s Belarusian and Ukrainian developed, but not Russian. In Muscovy (or the predecessor of the Russian Empire), Ruthenian was known as Litovskii (literally, “Lithuanian”), because it was official in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Today’s Lithuanian (Lietuvių), which is a Baltic language, has nothing to do with this Litovskii-Ruthenian. On the other hand, the Slavic speech of Moscow was known in Ruthenian as Moskovska (“Muscovian”) in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The prestige of Ruthenian was so high in the early modern period that Muscovian officials took care to learn it, before progressing to Polish and Latin, and then to German and French. Hence, numerous Ruthenian linguistic loans persist in Russian to this day. What is more, Ruthenian also functioned as the main conduit through which numerous Latin and Polish loanwords entered Russian. Significantly, Lomonosov modelled his grammar of Russian on the Ruthenian scholar and Archbishop of Połock (today, Połack in Belarus) Meletius Smotrytsky’s influential grammar of (Church) Slavonic (Slavenski), which was first published in 1619 in Jewie (today, Vievis in Lithuania).

In the 1880s, the policy of Russification was rolled out across the entire European section of the Russian Empire. This move necessitated the replacement of German, Georgian, Moldovan (Romanian) or Swedish, which were still official in different provinces, with Russian. At that time, a new appropriately imperial name of Russian became widespread, that is, the Velikorusskii or “Great Russian language”. This novel coinage started gaining currency, thanks to Vladimir Dal’s popular and influential four-volume Tolkovyi slovar’ zhivago velikorusskago iazyka (Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language), which was released in 1863-66. Two further editions followed in 1880 and 1903. Demand for this reference remained so high and its authority so prevalent that even the Bolsheviks resigned themselves to reprinting this dictionary twice, in 1935 and 1955.

The dictionary’s first edition coincided with another of the Polish-Lithuanian nobility’s anti-tsarist uprisings that took place in 1863-64. The suppression of this insurrection entailed doing away with the last remaining cases of the employment of Polish in some administrative roles and as a medium of education. On top of that, the previously scant use of Belorusskii or “White Russian” (Belarusian) and Malorusskii or “Little Russian” (Ukrainian) for literary and ethnographic ends was banned from printing. The decision was followed with the official espousal of the theory that Little Russian and White Russian are simply narechiia (“unimportant peasant dialects”) of the Great Russian language. As such, in the imperial view, these narechiia were destined for extinction. All the tsar’s “civilised” subjects were to speak and write in Great Russian only.

Lost in translation

Between the 1860s and the turn of the 1920s, across the Russian Empire, school lessons of the country’s language and literature were labelled respectively as “Great Russian language” (Velikorusskii iazyk) and “Great Russian literature” (Velikorusskaia literatura). Titles of textbooks for these school subjects followed suit. Obviously, in this context the adjective “great” did not promote any superior qualities of this language or literature, but rather was part of the then official name of the Russian language, that is, “Great Russian”. In Russian this name was written as a single word, Velikorusskii. However, the conventions of English spelling required that in translation it became two words. In this manner, ambiguity was introduced to English literature on whether the adjective “great” is part of the name of Russia’s official language or rather an evaluation of this tongue’s “inherent greatness”, as the present-day Kremlin’s propaganda would like us to believe.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 replaced the tsarist regime with Soviet totalitarianism. The old world was to be destroyed, giving way to a “radiantly communist future”. In order to attract the former empire’s reluctant populations to this project, in 1922, the revolutionary government announced a struggle against Velikorusskii shovinism (“Great Russian chauvinism”). All the empire’s ethnic languages were permitted and actively encouraged in official use in administration, schools and publishing. Russification was over, until it was reintroduced with a vengeance in 1938. In the Soviet Communist Party’s view, Russian was to become the single socialist language of the Soviet classless people and of global communism.

Although the language’s name was modestly returned from bombastic “Great Russian” to the modest moniker of “Russian”, now the Soviet policy of Russification – in a quite megalomaniac fashion – targeted the entire world. The Kremlin used Russian culture and literature to justify and popularise this push for a truly global Russian. Soviet propaganda went into overdrive. Following the quickly terminated two-year-long totalitarian alliance with Berlin, the Soviet Union joined the Allies against nazi Germany in 1941. Then a brand new collocation velikaia Russkaia literatura (“great Russian literature”) made a showy entrance. Paradoxically, this new term had an easy ride on the back of the strenuously banned tsarist name of “Great Russian” language and literature. In Russian, the difference between Velikorusska and velikaia Russkaia literature is clearly discernible, though tends to be confusing.

However, in English translation the difference is all but lost, apart from the hard to interpret capitalisation. In English Velikorusska literatura, or literature composed in the Great Russian language, morphs into “Great Russian literature”. Meanwhile, the Soviet propaganda’s laudatory label velika Russkaia literatura, translated as “great Russian literature”, becomes indistinguishable in English from the other term. Although due to the Soviet struggle against Great Russian chauvinism, the English term “Great Russian literature” declined rapidly in the early 1920s. Nevertheless, its remaining uses fed into the skyrocketing rise of the collocation “great Russian literature”, beginning in the 1940s.

Seeing more clearly

Prior to the Bolshevik Revolution, the English phrase was an inconspicuous statement of fact, namely, that a certain literature happened to be composed in the Great Russian language, which nowadays we refer to as “Russian”. Yet, during the Second World War, the new “friendly” Soviet propaganda left the West with a hard to discern and essentially toxic legacy in the form of the set expression “great Russian literature”. After having been conditioned to endorse the term “Great Russian language” in the late tsarist period, westerners were expected to accept the new but slightly rehashed obsolete expression easily. And indeed, they obliged. While the tsarist term came with no subtle message, with the new one Soviet propaganda coaxed the West to unquestioningly believe in some inherent “greatness” of Russian literature. As though the quality, variety and sheer output of English, Spanish or French literatures was not actually “greater” than their Russian counterpart.

The post-Soviet Russian Federation banks richly on this innocuous legacy. Nowadays, the apparently neutral but in reality ideologised expression has become part and parcel of the country’s arsenal of hybrid warfare. As a result, the Kremlin has no difficulties in shaming the West for even the slightest attempt to rein in the offensive use and spread of Russian literature and culture during a time when Russian military forces wage total war on Ukraine with horrific consequences, including acts of genocide. In this respect, even western specialists in Russian studies duly toe the line. All reverently parrot the phrase “great Russian literature”, though some are more sceptical about Moscow’s claims that neither the Ukrainian language nor Ukrainian literature exists. Or that Ukrainian literature is “poor and folkloristic”, which is obviously a skewed Russian colonial view of the Ukrainians and their modern and vibrant culture. Westerners should not trust this Russian opinion and check the facts on the ground, above all by enjoying more excellent books from Ukrainian literature.

When the West was not looking, the Kremlin weaponised not only Russian but also some elements of English. Let us be clear, when the collocation “great Russian literature” is invoked uncritically, the person using it consciously or not does Moscow’s bidding. Beware.

Tomasz Kamusella is Reader (Professor Extraordinarius) in Modern Central and Eastern European History at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. His recent monographs include Politics and the Slavic Languages (Routledge 2021) and Eurasian Empires as Blueprints for Ethiopia (Routledge 2021). His reference Words in Space and Time: A Historical Atlas of Language Politics in Modern Central Europe (CEU Press 2021) is available as an open access publication.

Please support New Eastern Europe's crowdfunding campaign. Donate by clicking on the button below.