The Eastern Partnership: Which way from post-Soviet?

The countries in both Russia and the European Union’s neighbourhood are commonly known as the post-Soviet states. However, as their Soviet past becomes more distant, their future horizons remain unclear.

October 6, 2013 -

Yegor Vasylyev

-

Articles and Commentary

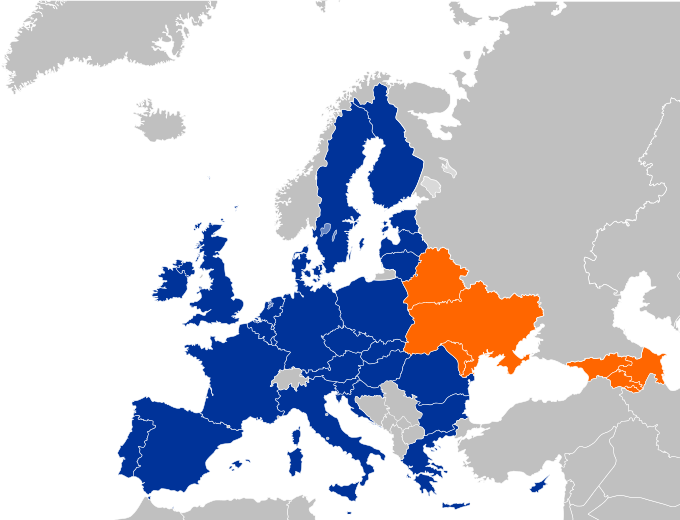

680px-EU-Eastern_Partnership.png

Apart from declarations, none of the Eastern Partnership countries have pursued a determined long-term perspective or aim.

In an ideal version of their westernisation, the countries could form a new region to take the Euro-Atlantic path, similar to the Central European countries before them. However, the internal and external factors that influence their choices are substantively different, and the countries are in a unique situation of their own.

Vigilant Russia

Unlike its neurotic and disconcerted reactions to the NATO and EU accession of the CEE and Baltic states, Russia has been quite assertive in countering a possible turn westwards of the new Eastern Europe bloc.

The unequivocal rhetoric of Vladimir Putin and his messengers is accompanied by intensifying pressure. Both in words and actions, the Russian leader and his team are showing off around Russia’s neighbourhood as the first guy in the village (pervyi paren na derevne).

Ukraine, who, in Putin’s words, comes from the very same people as the Russians, part of which, he claims, suffered for centuries at the hands of its Western neighbours, is on track to sign the Association and Free Trade Agreement with the EU in November. Therefore, in August, Ukraine was given a taste of the fully-fledged blockade of its imports to Russia. Most recently, Putin’s adviser Sergey Glazyev openly threatened Ukraine with default in case the Agreement comes into force.

Armenia, a country whose borders are co-patrolled by Russian forces, is in Glazyev’s vision essentially no different to Russian than the Kaliningrad Oblast. Following a meeting with powerful Moscow-based Armenian oligarchs and an audience with Putin during his visit to Moscow, Armenia’s president, Serzh Sargsyan, announced that Armenia will join the Customs Union. The long negotiated agreements with the EU have been effectively stalled.

Moldova’s authorities, however, have no intention of following Armenia’s lead, although the Russian Federal service on customer’s rights protection has banned Moldovan wine. Russian deputy prime minister Dmitriy Rogozin has publicly expressed his sincere hope that Moldova, which has declared its resolve to alleviate its current 100 per cent dependence on Russian gas supplies, “will not freeze this winter”.

Belarus is a founding member of the Customs Union, but its longest-serving president, Alyaksandr Lukashenka, still dismisses the surrender of the family jewels, which happens to produce most of the country’s GDP, to Russia. In the latest twist of his uneasy relations within the Slavic brotherhood, he is coming under another wave of economic pressure, once again being reminded how vulnerable his Russia-subsidised “socially-oriented model” is.

Georgia, where outgoing prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili remarkably has “no opinion at all” on the issue, sees Russian troops installing fences on the borders of its breakaway region of South Ossetia. Even Anna Chapman has struck again, paying a very public trip to the conflict region of Qarabag, right after the avidly promoted but not really productive August visit to Baku by Putin.

All this is taking place amidst growing discontent within Russia’s major regional integration project. The Eurasian Customs Union has so far no strikingly positive impact to boast, with one party – Russia – dominating, while the others – Belarus and Kazakhstan – turn to an increasingly piecemeal approach. However, this does not stop Russia’s assertive diplomacy from leaning over the post-Soviet Bloc to the “already runaways”. Lithuania has most recently also faced trade curbs and is currently going through harsh gas negotiations.

Post-Soviet decision-making

This overarching Russian political and economic will makes the usual post-Soviet balancing approach to foreign policy increasingly problematic. The mantra repeated once and again by the countries’ rulers about finding a middle way to cohabit both directions (or, in words of both Alyaksandr Lukashenka and Viktor Yanukovych, “two monsters”) comes to loggerheads with the substance of the new commitments. So, what next?

In a list of differences between the post-Soviet Eastern Partnership countries and the CEE EU members, there are two main factors. First, the political culture of the post-Soviet political players and their view of power lead to their decision-making being guided by the interests of their narrow elite networks – not by doctrines or beliefs. Thus, in practice, even the most crucial decision could be reversed or downplayed.

Second, in the post-Soviet world, democratic procedures, even if formally observed, work in a special way. As far as there are no more ideological tyrannies in the region, any regime, however semi-authoritarian, is dependent on the support of the majority. If secured, it is perceived if not as an unabridged authority, then a mandate to pursue its own agenda. Effectively, this means that public opinion matters. But, what are the prospects of geopolitical choice in these perspectives?

Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine

Belarus and its “last European dictator” are going through some challenging times. Approaching his 20th year in the office, Alyaksandr Lukashenka is likely to face more problems in maintaining socio-economic promises, which lie on the basis of the lasting social contract with his core post-Soviet, non-ideological electorate. At the same time, he has neither capable opposition contenders, nor a countrywide movement to confront his authority.

Quite experienced in Russian ways and methods of cooperation, Lukashenka, who handles all the threads in a knitting ball of the country’s elites, is not ready to take more of Vladimir Putin’s integration offers, and knows all too well what a sign of weakness means in the post-Soviet political theatre. “What’s with our Western direction?” he has recently questioned Foreign Minister Uladzimir Makey, who is seeking “normalisation” and a “pragmatic character” in relations with the EU. There is an on-going strengthening of popular support for the country’s rapprochement with Europe, which its largely populist leader might find worth taking into account. Some allege the country is approaching another European thaw. As the most experienced balancer on the block, he well might contemplate a new move from the last heel to Moscow, but that, of course, will have nothing to do with real democratisation.

In Moldova, despite the announcement of a “velvet revolution” by the Communist Party, the next parliamentary elections are still likely to wait until 2014. The EU-oriented government, headed by experienced diplomat Iurie Leancă, will not take a U-turn in its geopolitical direction, whatever the circumstances. However, public support for this vector of integration is not that strong. The ever-present issue of Moldova’s identity, frustration with the pro-European coalition, which is no stranger to typical post-Soviet interests-based governance, and their incapability to deliver socio-economic improvement, might lead to a change of government in the aftermath of the elections. In such a case, an overhaul of foreign policy and geopolitical orientation may also be possible.

Ukraine, during its early independent years has suffered “post-Soviet schizophrenia” caused by a split in its national identity. Only 22 years since the fall of the Soviet Union has passed and the country is experiencing a shift, with support to Ukraine-ness and the European vector prevailing and expanding Eastwards. Potential for a dramatic increase in public support for integration with Russia is low. The pro-Russian political camp is in disarray, lacking capable political representatives. This makes the Communist Party, whose electorate is strictly limited to around a 10-per-cent share, the most electorally visible advocate of the Eurasian integration.

Factors of the current energy and economic dependence suffice neither the president and his orbit, nor the networks of oligarchs to turn their full support to this vector. There is a shared conviction among both that the Russia-led project in the long-term perspective contradicts their political and economic interests. Aware of the sociological map, Viktor Yanukovych is currently rebranding, building up his image as a statesman and Europeanist in an attempt to expand his stalwart 20-25 per cent electorate. Still, among the three real contenders for the 2015 presidency, Yanukovych is the only professional graduate of the post-Soviet school of politics, which makes any geopolitical moves more likely.

Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan

Georgian officials at all levels have stressed their commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration, which is strongly supported by the population. The country is facing presidential elections on October 27th, but its most powerful man, Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili, claims he will resign and leave politics at the height of his influence. For the post-Soviet, this is as unprecedented as suspicious in terms of a tradition of grey-cardinals, backstage puppeteers and other informal patterns in governance.

Ivanishvili, who is known to have made his billions in Moscow in the early 1990s, cannot escape speculation about his connections within the Russian elite. His Georgian Dream political coalition still enjoys popular support. But the country’s political landscape, with its usual centralisation and strong leadership, is about to enter a new situation, when a genuine leader of public opinion ceases to be an official political player. Ivanishvili’s recent statement on Russia’s possible joining of NATO and the EU, which has no ground whatsoever in the position of the Russian authorities, add up to the ambiguity about his foreign policy views. The country’s territorial problems are far from resolved and its vulnerability to foreign pressure is high.

The Armenian president’s choice of the Customs Union, despite making the headlines, in essence, comes as no surprise. The country’s ruling elite and its almighty oligarchs have maintained close connections to Russia since Soviet times. The social tension in the country is rather high and the economic situation is poor, but its highly problematic relations with its neighbours has for years caused severe dependence on Russia, with which Armenia has no common border. This has also secured the support of the majority in favour of integration with Russia. Although in recent years this support has decreased, the decision announced by Serzh Sargsyan was met with little protest. Whoever holds the power in Yerevan, the impasse in the country’s regional relations is likely to halt any meaningful developments in its European integration.

Azerbaijan for the moment seems to be the most stable of all Eastern Partnership countries. The public, largely content with the long-standing President Ilham Aliyev, who is set to retain his office for the third time following the October 9th elections, does not distinctively favour any direction of integration. The president’s grip over the country’s power networks is no weaker than that of his Belarusian counterpart, and the alternative networks of oligarchs, the so-called Billionaires Club, are confined to Russia. Quite aware of its long-term energy resources and strategic importance of Caspian hydrocarbons for the geopolitical conundrum of the region, official Azerbaijan aims to bolster its regional position and is on track to do so in the coming years. Due to these specifics, Vladimir Putin is unable to apply the same sort of pressing arguments as in Russia’s Western neighbourhood, and any type of unilateral surrender to his integration projects by the current Azerbaijani regime is not possible.

The EU: the need for a practical approach

There are few rules in the post-Soviet game of politics practised in every Eastern Partnership country. The Russian Federation’s leader, with his confidence on the international arena boosted, knows this all too well. The language, most common for the post-Soviet political theatre, is one of pressure and cajoling, followed by formal and informal offers. Russia shows every sign of the determination to speak up, although the EaP countries are increasingly reluctant to follow its words too closely.

The EU is more substantive and certain in its reactions to developments in the Eastern Partnership than ever before. This brings hopes for a more targeted approach to engage the EaP countries. It is true that democratic standards in the region are way lower than in any CEE country, but given their past and the realities of the immediate post-Soviet period, demanding the triumph of rule of law here and now has provided little effect. The real independence of the EaP countries and the ability to decide their own fate also seems to be crucial.

There is a need for the diversification of approach to each country, taking into consideration their specifics. In some, the post-Soviet elites’ self-preservation instinct can be used to help the countries uphold their independence and prospects of democratisation. EU economic offers are crucial in this case. Others have fundamental factors hampering their European integration. And all need Europe’s engagement with their societies at the lowest possible level to sustain the consolidation of European values and European choice.

The post-Soviet situation of the Eastern Partnership countries is unique, and thus the way forward also requires a special approach from those who want to support it.

Yegor Vasylyev is an analyst specialising in politics and transition of post-Soviet states. He holds an LLM in European Law from the London School of Economics and Political Science, where he was a British Chevening Scholar in 2009-2010, following five years in the Ukrainian civil service.