The short-lived Weimar cultural scene

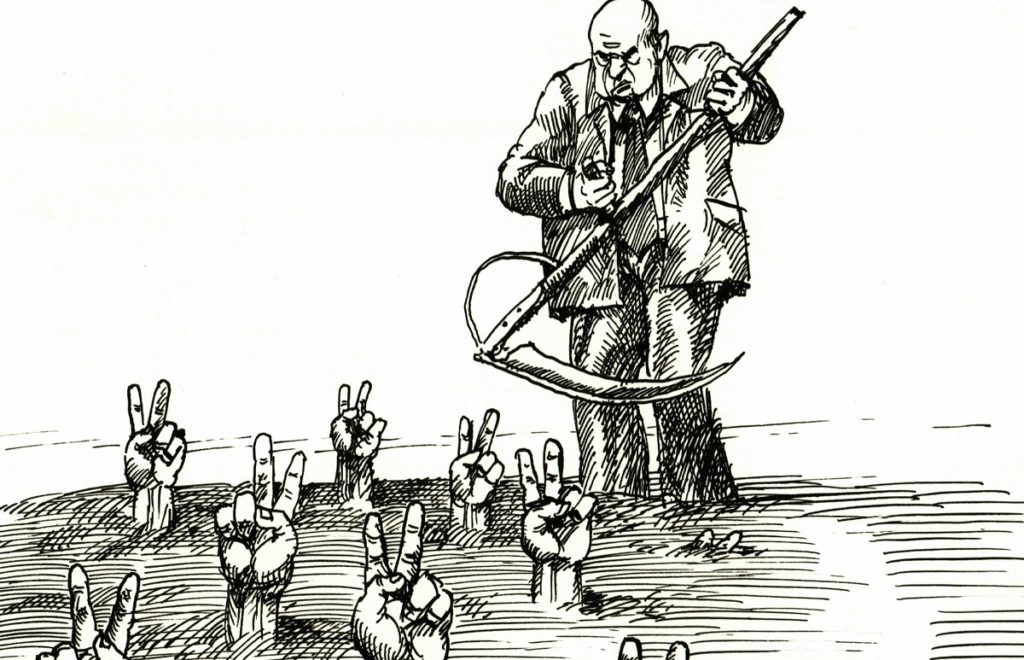

Culturally speaking, the Weimar Republic was an extremely vibrant period in German life. It was a time of new artistic trends which included the works of great artists like Marlena Dietrich, Thomas Mann and Gerhart Hauptmann, to name just a few. This was also the period of the theatre of Max Reinhardt and Bertold Brecht, who’s Threepenny Opera was enriched by the music of Kurt Weille. In addition, this period saw a rapid development in the visual arts, including film and photography.

November 12, 2019 - Kinga Gajda