The price of democracy in Montenegro

The electoral defeat of the Democratic Party of Socialists in Montenegro opens a new chapter in the country’s politics. It remains to be seen what the reaction of the parties representing the minorities in the country will be to the new situation of their traditional allies.

November 13, 2020 -

Austin Doehler

-

Articles and Commentary

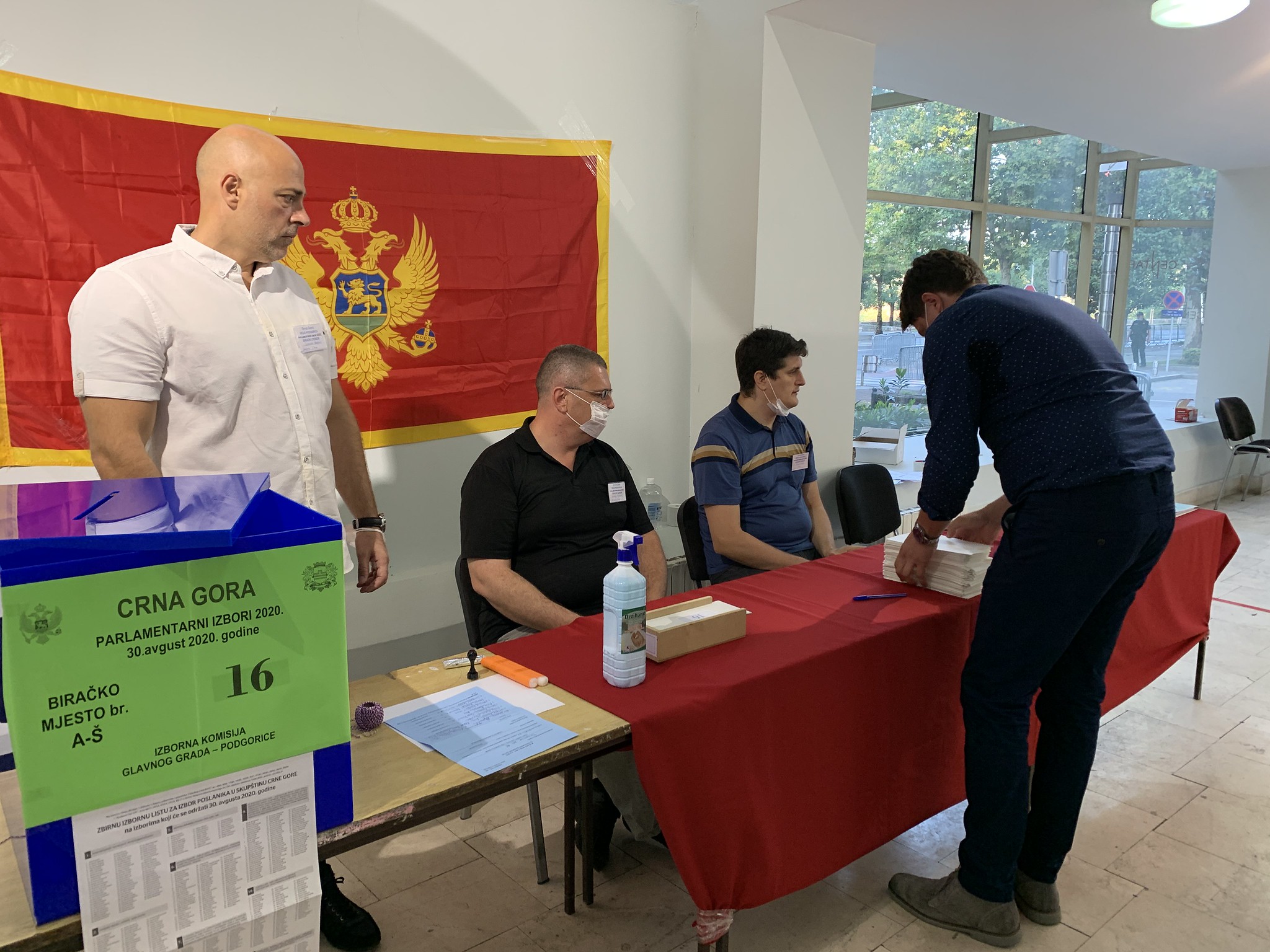

Election observation, Montenegro, August 30th 2020. Photo: OSCE Parliamentary Assembly flickr.com

Until recently, if one had to select a single word to describe the state of Montenegrin politics over the past several decades, “boring,” “predictable,” and “banal” would have been strong contenders. Since 1991 Montenegrin politics have been dominated by the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), the successor party of the Montenegrin branch of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, which was the only legal political party in Yugoslavia from 1945-1990.

However, Montenegro’s parliamentary election in late August provided a surprising turn, as the DPS was only able to secure a little over 35 per cent of the vote and fell, along with its traditional coalition partners, just shy of winning a majority in parliament, securing 40 out of 81 seats. This leaves space for a new government to be formed comprised of three opposition factions that together won 41 seats, giving them the slimmest possible majority. Montenegrin President Milo Đukanović has formally given the mandate to form the new government to the leader of the main opposition faction, and an agreement in principle between the three factions to do so was recently reached.

Ostensibly, the electoral defeat of DPS should be seen as an unequivocally positive step in Montenegro’s political development. Similar to the political parties that have been at the helm, there has been significant continuity in the individual who sits atop Montenegrin leadership these past few decades. Since 1991, Đukanović has been in power virtually uninterruptedly as either the country’s prime minister or president, all in addition to being the leader of DPS. Đukanović is notorious for his ties to organized crime to the point where he has often been accused of operating Montenegro like a “mafia state.”

Despite the fact that Montenegro joined NATO in 2017 and remains one of the countries furthest along in the EU accession process, the pervasive corruption that has existed under Đukanović has had a corrosive effect on Montenegro’s democratic institutions. In a report from earlier this year, Freedom House downgraded Montenegro’s ranking from a “semi-consolidated democracy” to a “transitional/hybrid regime.” While Đukanović may not have literally been on the ballot in August and barring any unforeseen circumstances will remain in power at least until 2023, opposition leaders across the board framed the election as a referendum on his regime.

For those who care deeply about the future of democracy in the Western Balkans and the fight against corruption around the globe, the repudiation of a leader like Đukanović through the electoral process ought to be nothing but welcome news. However, things are not quite that simple. While the election result was due undoubtedly in part to Đukanović’s decades of corruption, the catalyst was the fact that he picked a fight with the most trusted institution in the country: the Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC).

In December of last year, the Montenegrin Parliament passed a controversial law that requires the SOC to be able to prove the rightful ownership of its property dating back to before 1918, when Montenegro joined what would eventually become the Kingdom of Yugoslavia; if it is unable to do so, then the state would have the right to seize the property. This caused significant backlash, resulting in months of protests led by clergy from the SOC.

Regardless of the merits of the law or validity of the protests, some troubling omens for Montenegro’s political stability became apparent. The vote on the law itself was marked by violence when eighteen members of parliament from the pro-Serb bloc were arrested for storming the proceedings and hurling firecrackers at their colleagues. While not overtly violent, the SOC as an institution also serves as a politically destabilising force in the country; it is extremely close to the Serbian government and even acts as a soft power tool for not only Serbia, but Russia as well. It was strongly opposed to Montenegro’s independence from Serbia in 2006, and even to this day serves as one of the main vehicles for Serb nationalism in Montenegro.

The results of August’s election did little to alleviate concerns about the influence of Serb nationalists in the next government. The coalition that won the lion’s share of seats in the likely new government (27 out of 41 seats), For the Future of Montenegro (ZBCG) is comprised largely of the very same Serb nationalist political actors that violently stormed the parliament during the vote on the religious property law. The largest bloc of parties within ZBCG is the Democratic Front (DF), which advocates for a restoration of the Montenegrin-Serbian union state.

The potential for the other factions in the expected new governing coalition to act as a bulwark against ZBCG’s more extreme tendencies is dubious. Peace is Our Nation (PON) is a two-party coalition that holds ten seats, and United Reformed Action (URA) is a party that holds four. While both parties are pro-European and have sought to get ZBCG to agree to principles such as maintaining a pro-West foreign policy and allowing the government to be led by experts, ZBCG is insisting that they receive some key ministerial posts.

Given the outsized influence that ZBCG has on this potential coalition, having almost triple the number of seats of the next largest faction, it appears unlikely that PON and URA will be able to moderate ZBCG’s influence. On the contrary, it is more likely that they will be convinced to form a government in which ZBCG’s preferred policies will be pursued so as not to risk triggering snap elections in which the DPS could return to power or ZBCG’s position could be strengthened. The pressure to form a government by any means necessary will only grow if any of the Albanian and Bosniak minority parties, which are traditionally allies of DPS, wind up joining the new government.

All of this serves as a useful reminder that sometimes democracy comes with a price. Those who care about Montenegro’s democratic development while simultaneously wanting to see it continue its pro-West foreign policy are seemingly caught between a rock and a hard place. This requires holding two competing ideas in tension: that the democratic ouster of Đukanović was in itself positive as it shows that Montenegro is capable of having relatively free and fair elections in which opponents to the current government have the ability to come to power by peaceful means and that the results of this peaceful transition may very well, from purely a policy perspective, leave Montenegro worse off than it was before.

In times like these it is important to reaffirm democracy as a good in and of itself and as more than just a means to an end for achieving one’s preferred policy goals. Those who wish to see a Montenegro that is both democratic and Western-oriented ought to be encouraged by the process in which the probable new government will come to power and stridently oppose the policies that it is likely to pursue.

Austin Doehler is a visiting scholar at the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement, where his research focuses on right-wing populist nationalism, public corruption, and Chinese influence, with a regional focus on the European Union and Western Balkans. Before joining Penn Biden, he was an area studies fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, where he conducted research on the impacts of China’s Belt and Road Initiative on the Western Balkan-EU integration process. His analysis has been published in several outlets, including War on the Rocks, The Hill, and The National Interest. He holds an M.A. from George Washington University.

Dear Readers - New Eastern Europe is a not-for-profit publication that has been publishing online and in print since 2011. Our mission is to shape the debate, enhance understanding, and further the dialogue surrounding issues facing the states that were once a part of the Soviet Union or under its influence. But we can only achieve this mission with the support of our donors. If you appreciate our work please consider making a donation.