Hostage to the generals

On November 9th 1918 a republic was established in Germany. It was one of the unintended outcomes of the First World War. The Hohenzollern family, which ruled Germany since 1871, lost power as a result of the war. It is difficult to fully understand the 14-year long history of the interwar German republic without looking at the causes which brought it to life. The same factors, in fact, are the ones which brought it to an end. Had it not been for the madness of Emperor Wilhelm II, Germany would have probably remained one of European constitutional monarchies. The sudden and unexpected abdication of the emperor in 1918, as well as his unexpected call to make peace with the Allied Forces, truly shocked the German public. Its citizens experienced four years of sacrifice to face a disgraceful capitulation in the end.

November 12, 2019 -

Andrzej Zaręba

-

History and MemoryIssue 6 2019Magazine

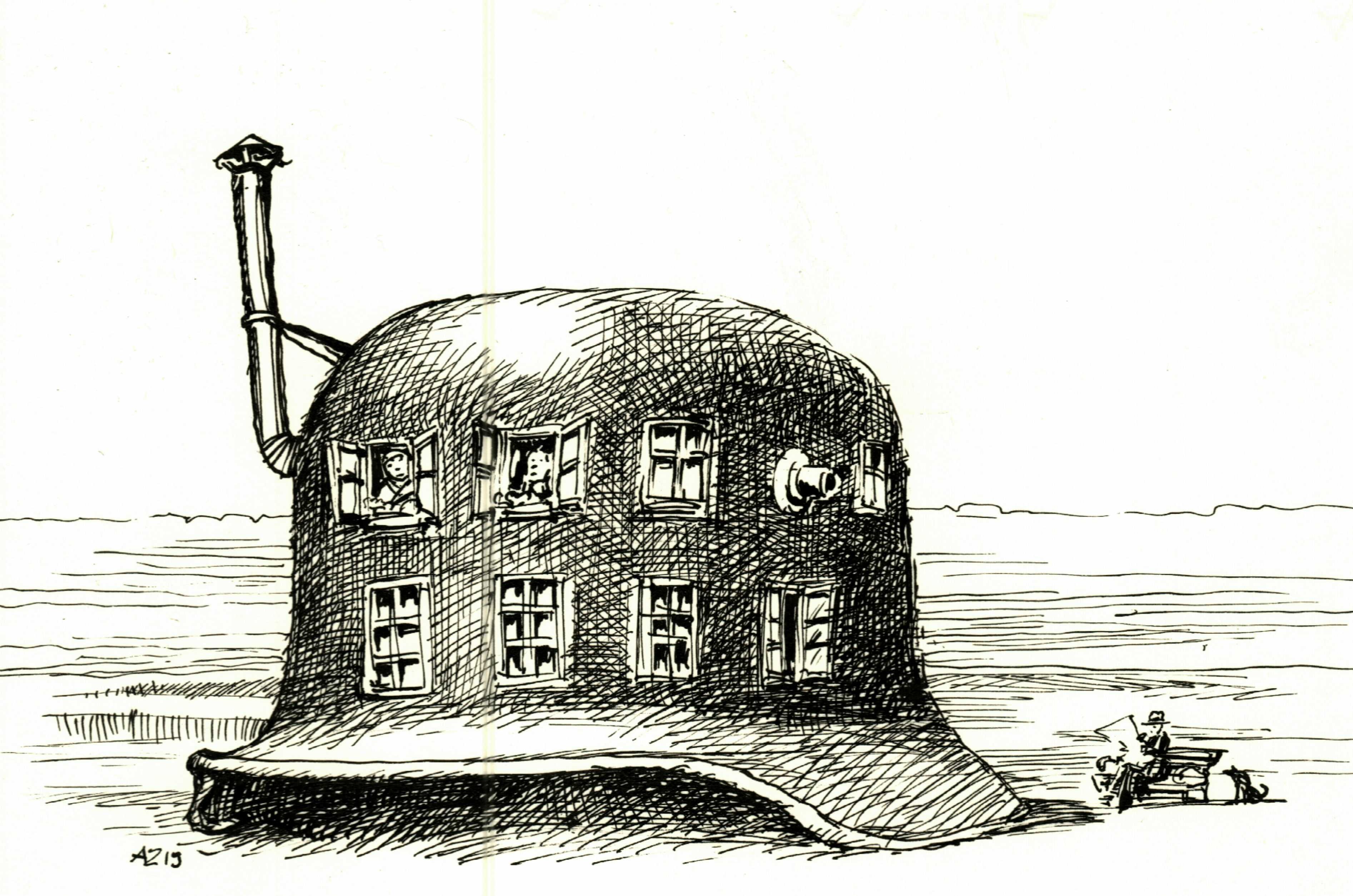

illustration by Andrzej Zaręba