Little change in the Belarusian economy

According to official projections, Belarus is to reach 3.5 per cent GDP growth this year. Less optimistic is the forecast of the IMF which believes growth will be at only 0.7 per cent. The National Bank of Belarus, in turn, assumes inflation will not pass seven per cent. Regardless of the source, the predicted growth is not going to result in any form of structural change to the Belarusian economy. Rather it will be a reflection of global economic prosperity and higher gas prices.

September 1, 2018 -

Anna Maria Dyner

-

Articles and CommentaryIssue 5 2018Magazine

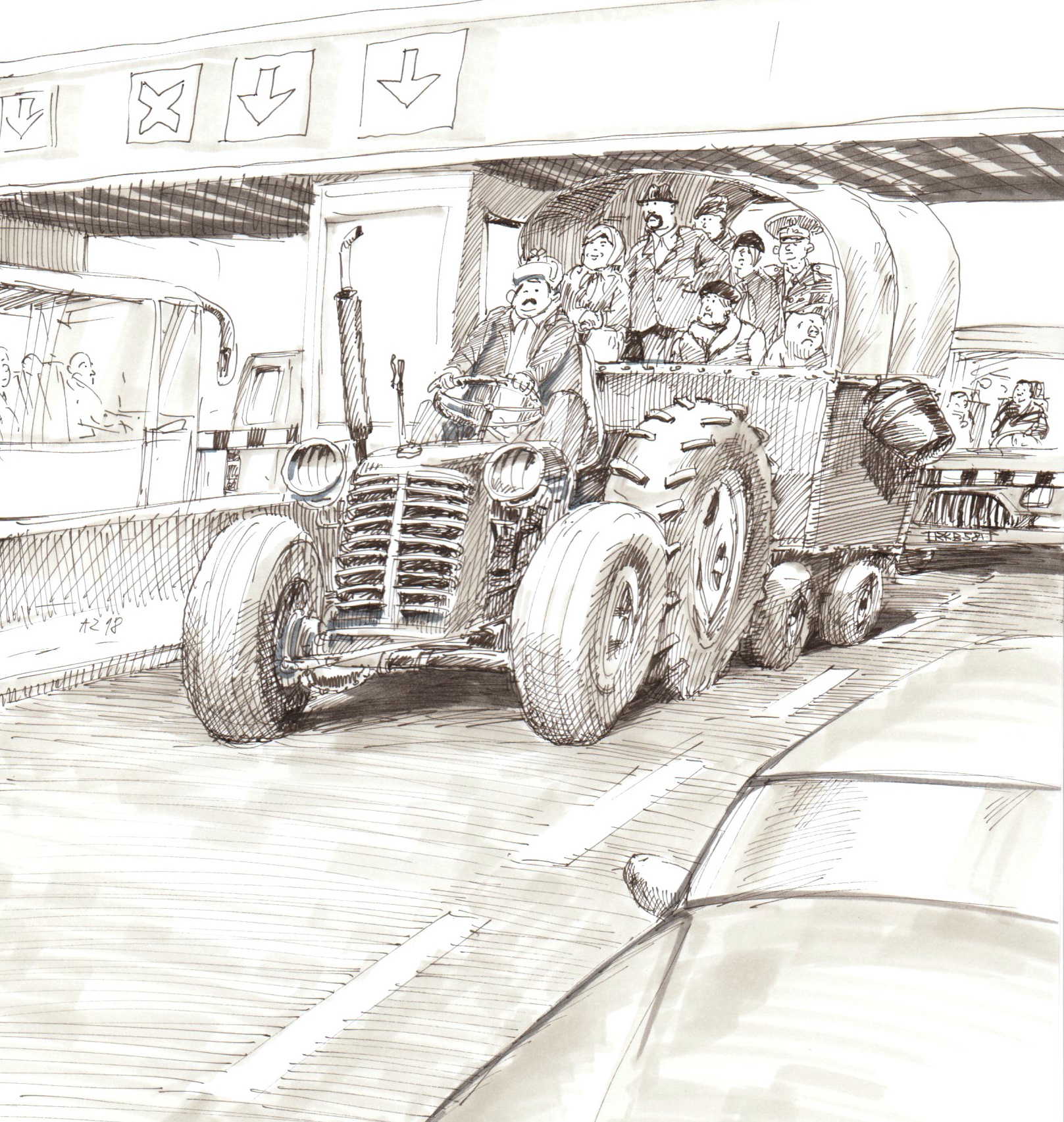

Illustration by Andrzej Zaręba