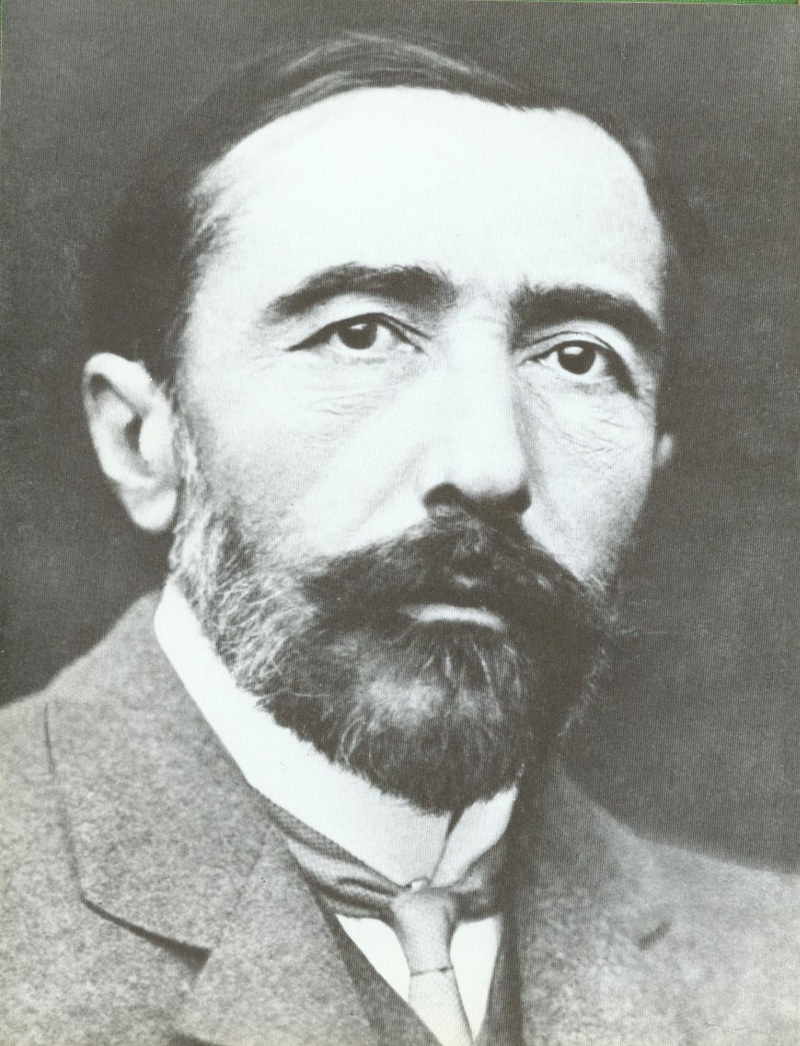

The first transnational author

Both at sea and on land my point of view is English, from which the conclusion should not be drawn that I have become an Englishman. That is not the case. Homo duplex has in my case more than one meaning.

– Joseph Conrad in a letter to Kazimierz Waliszewski, December 5th 1903

September 15, 2017 -

Laurence Davies

-

Stories and ideas

Kazimierz Waliszewski had written two articles about Joseph Conrad, one in French for the Revue des Revues and one in Polish for Kraj (a Krakow-based journal one of whose founders was Conrad’s father – Apollo Korzeniowski). Waliszewski lived in Paris and his travels were mainly to the archives of the great imperial cities of Europe, garnering materials for books on Polish and Russian history and literature. Meanwhile, Conrad had worked around the globe in steam and under sail, and for the last ten years or so had been drawing on – but not just reproducing – his experiences in such places as Borneo, the Congo, Singapore, Bangkok and the Australian colonies, not to mention the great oceans. Yet they were both exiles long separated from their homeland. Although we have only Conrad’s side of the correspondence – nine letters in all, some in Polish, some in French – it is clear that in Waliszewski Conrad found a sympathetic and a thoughtful reader.

Double life

Conrad’s story is one both of steadfastness and hard circumstances. His parents and most of his extended family were devoted to the restoration of Polish independence, which was lost in the partitions of 1772, 1793 and 1795 as Russia, Prussia and Austria divided up the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth among themselves. He grew up carrying a burden of sacrificial duty, an imperative he admired for its demands on courage and tenacity but in his life as exile, sailor or author, could never follow absolutely. As he told his close friend Robert Cunninghame Graham, who was grieving the loss of his wife: “Living with memories is a cruel business. I – who have a double life, one of them peopled only by shadows growing more precious as the years pass – know what that is.” He had become a British subject on August 19th 1886 at the age of 29, not only as a practical necessity but as a demonstration of loyalty to a nation whose institutions he admired and whose merchant navy had afforded him a career.

It would be foolish, of course, to take Conrad’s description of himself as a double man, a homo duplex, for a binding judgement on his character. People who write letters (or emails, or tweets) are in a sense performers, even before an audience of one. Nevertheless, his summing up is so resonant an answer to those who refuse to acknowledge multiple or overlapping identities that it speaks not only for Conrad but for all those who feel the pressure to deny some part or other of their selves. Conrad returned to the theme of doubleness with Homo duplex– an ancient phrase, springing from Greek and Egyptian mystical traditions, but used more recently to describe conflicts between reason and unreason or the social and the antisocial, but for Conrad, immersed in at least two national traditions and shaped by several others, particularly the French, either/or is a less satisfactory principle of survival than both/and.

In 1957, to honour the centennial of Conrad’s birth, the BBC Third Programme broadcast a beautifully orchestrated set of interviews with those who had known him – family members, members of his household, friends, and colleagues. Józef Retinger, a scholar and political visionary from Galicia, recalled that “he never spoke one single language with me – he was jumping from English to Polish, from Polish to French and vice versa, all the time. His Polish was absolutely perfect as far as conversation was concerned, with this sing-song of his own part of Poland.”

Conrad’s exposure to a multitude of cultures began very early. He passed the first ten years of his life in the Russian Empire. Part of that time was spent in exile to Russia proper, but the rest was in, to give them their present-day Ukrainian names, Berdychiv, Zhytomyr and Chernihiv. In these towns, at least four secular languages were spoken: Ukrainian (then known as Ruthenian), Russian (the language of authority), Yiddish and Polish. Three sacred languages were in ritual use: Hebrew, Latin and Church Slavonic; and in the Korzeniowski family there were books to read and translate in French and English. Conrad’s parents were passionately devoted to the cause of Polish independence but they also recognised the political desires of others in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. After the death of his mother (her health broken by her time in Vologda) Conrad and his father were given leave to exchange the Russian for the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where Konradek (as his family called him) added German to his repertoire.

Retinger also recalled that Conrad’s “French was very good and his English conversation very bad”. Here is one of the great paradoxes of Conrad’s life. Other witnesses confirm his difficulties with English pronunciation – with “th” for example – and, even though he had become a British subject in 1886, the aura of foreignness persisted. When he died in 1924, Virginia Woolf hailed his genius and the beauty of his prose, but still referred to him as “our guest”. In spite of those difficulties, he had a wonderful ear for rhythm and cadence – one of the finest in English literature. Describing the scene at Conrad’s burial, Robert Cunnninghame Graham wrote: “The priest had left his Latin and said a prayer or two in English, and I was glad of it, for English surely was the speech the Master Mariner most loved and honoured in the loving with new graces of his own.”

A stranger and at home in many places

As books travel through time and space, their significance changes with the cultural climate. In the 1920s, especially in the United States, Conrad’s novels and stories seemed romantic and exotic and found great favour with filmmakers, while the extraordinary political novels, like Nostromo, The Secret Agent and Under Western Eyes, were pushed aside. To members of the Polish Home Army, the largest resistance movement in Nazi-occupied Europe, Conrad epitomised courage and fidelity in a world full of perils. Vanguard novelists – such as Carlo Emilio Gadda and Italo Calvino in Italy, Ewa Kuryluk in Poland, Graham Greene in Britain, André Gide in France, Lao She in China and William Faulkner in the US –have recognised Conrad’s ironic fierceness and mastery of disruptive narration. More recently the emphasis has fallen on his unflinching accounts of terrorism and, more controversially, his pictures of imperial subjugation. Most recent of all is the tendency to think of him as a transnational author, a stranger and at home in many places.

One aspect of this fascination with transnationalism lingers over the plight but also the resourcefulness of exiled authors. To take some other Polish examples, we could point to Adam Mickiewicz, Witold Gombrowicz and Kuryluk. Another aspect, or rather implication, of transnationalism is an acute awareness of migration of all kinds. When we go back to Conrad with that in mind, we find temporary or permanent migrants almost everywhere.

To cite just a few examples, Almayer’s Folly (his first novel) opens with a summons to dinner in Malay spoken by the wife of a Dutch trader frittering away his existence with dreams of gold. The first section of Under Western Eyes is set in St Petersburg; the other three are set in Geneva, among Russian emigrés, many of them revolutionaries. The passengers in “Typhoon” are Chinese labourers returning to their villages from “various tropical colonies”; their brassbound wooden chests contain “silver dollars, toiled for in coal, won in gambling-houses or in petty trading, grubbed out of earth, sweated out in mines, on railway lines, in deadly jungle, under heavy burdens – amassed patiently, guarded with care, cherished fiercely”. Conrad began The Secret Agent in the aftermath of the UK Parliament’s passing the Aliens Act of 1905, which for the first time stipulated immigration controls, a measure largely aimed at Jewish refugees from the Russian Empire. Meanwhile the Russian Imperial Government was lobbying hard for the expulsion of anarchists and other revolutionaries from the United Kingdom.

Nostromo deals with nationhood in Latin America, as Costaguana, a province rich in silver, secedes from the other provinces across the sierra. The cast of this epic novel includes: Italian followers of Garibaldi and a Genovese sailor with a genius for leadership; a locally-born mineowner of English descent and his English-born wife who has a better feel for the country than he does; a doctor with an Irish name irrevocably bound to the land by the traumas he has undergone; an itinerant Jewish merchant; a team of British engineers and railwaymen; the superintendent of a shipping company who will eventually retire back to England, doubtless taking with him his rich hoard of commonplaces; and a Europeanised costguanero journalist who has left the boulevards of Paris in order to promote secession.

In “Karain” (Tales of Unrest, 1898) we see yet other kinds of migration. The title character is Bugis, belonging to a seafaring people from Celebes (now Sulawesi), who has fought against the Dutch in Sumatra. Now he has taken over a small district on Mindanao, in the Philippines, at the time of writing a Spanish possession, but soon to be acquired by the Americans. As a minor rajah, he is the overlord of his own small territory, an empire in miniature. The English narrator and his associates deal in contraband weapons, living outside the law, yet nostalgic for England and able to turn on the imperial rhetoric when necessary. Karain has accidentally shot his dearest friend and is now haunted by his ghost. The Englishmen promise to lay the ghost with what they claim to be a powerful talisman, a silver sixpenny bit commemorating Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. The exorcism is successful, but in a final ironic turn, the Englishmen, having returned to dark and chilly London, long to be back in the tropics. One haunting has replaced another.

A heel-clicker and a hugger

Yet one of the most powerful treatments of immigrant identities comes without any kind of glamour short-lived or prolonged. “Amy Foster” (Typhoon and Other Stories, 1903) is set in rural England. It is a tragedy of errors, of mutual incomprehension. There is no overlapping of multiple cultures in this space where class rather than national origin provides the only variety. There is one new arrival, Yanko Goorall, whose name suggests an origin in the Polish highlands. He has been fleeced by a dubious emigration agency, packed off in an emigrant ship bound for North America which founders on the Kentish coast. He is the sole survivor of the wreck. He has no idea of where he is and when he first appears, filthy and dishevelled, the villagers take him for a madman. One person takes pity on him, Amy Foster, a farm servant with a stammer: “At night, when he could not sleep, he kept on thinking of the girl who gave him the first piece of bread he had eaten in this foreign land. She had been neither fierce nor angry, nor frightened. Her face he remembered as the only comprehensible face amongst all these faces that were as closed, as mysterious and as mute as the faces of the dead.”

Eventually Yanko finds work as a farmhand, using the experience he has brought with him from the Carpathians. Although he marries Amy, the villagers “never became used to him”. They are unnerved by his dancing and singing and overall exuberance, and completely fail to understand his body language. When Amy gives birth, Yanko is proud and delighted, but not long after he develops a fever. In his delirium, he speaks in his own language, and thus terrifying Amy, who runs off with the baby. All he has been saying though is a plea for water. Parched and bewildered, he dies.

There is something terribly moving about “Amy Foster”: both the story itself and the idea that this inarticulate couple, treated so sympathetically so understandingly should have come from a member of the Polish szlachta, a man in command of many languages and hardly ever at a loss for words in any of them. A kind and elderly lady who had known Conrad as a teenager once told me that he was “a heel-clicker and a hugger” – that is to say, by the conventions of the English upper-middle classes, too warm and yet too formal. Here is a literal incarnation of the Homo duplex, yet that doubleness or, better, multiplicity is what made him the great writer he was and is.

Laurence Davies is an honorary senior research fellow at the University of Glasgow and general editor of The Collected Letters of Joseph Conrad. He is also president of the Joseph Conrad Society in the United Kingdom.