To and for Europe

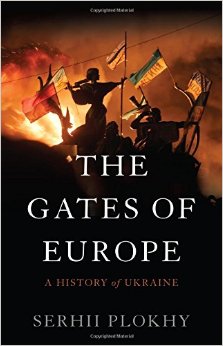

The Gates of Europe. A History of Ukraine. By: Serhii Plokhy. Publisher: Basic Books, New York, NY USA, 2015.

May 23, 2016 -

Tomasz Lachowski

-

Books and Reviews

Ukraine is not Russia was the title of a book written by the former President of Ukraine, Leonid Kuchma, and published in 2004 just before the Orange Revolution. Today, a decade after this political change, these words are even more indicative of the political and social landscape that characterises Kyiv today, despite the fact that the situation in 2015 is quite different from when Kuchma penned those words. The physical struggle against the Viktor Yanukovych regime and then the pro-Russian separatists trying to form a Kremlin-backed project called Novorossiya raises even more significant questions on Ukrainian unity, common history and identity; all of which are notably different to that which is found in Russia. These are the issues that are addressed in the book by Ukrainian historian Serhii Plokhy, which will be published in late 2015.

Plokhy is a world-renowned academic who has worked for many years at Harvard University. His specialisation, mainly the history of the former Soviet Union and Ukraine, together with his Ukrainian background has helped him draw a fascinating picture of the thousand-year-existence of the Ukrainian territory and people. Characteristically, Plokhy’s publication is not solely an academic work as it seeks to tackle some of the questions that are currently being raised in the geopolitical debate, including whether Ukraine belongs to the so-called Russkiy Mir (“Russian world”). Plokhy obviously takes his role as author seriously and offers the reader a disclaimer: “the history offered to you here is written with a sense of responsibility not only for the past but also for the present and future”.

Plokhy starts his history from the very beginning with the arrival of the Vikings (Norsemen) from today’s Ukrainian territory and their quick and peaceful assimilation with the Slavic tribes inhabiting the area between the Dniester and Dnieper Rivers. The author then moves on to tackle one of the first significant issues to be resolved, namely the legacy of the Kyivan Rus’, symbolised by the rule of Yaroslav the Wise (1016-1054). The question as to “who hold the keys to Kyiv” is, as Plokhy points out, still pending today. Ukrainians who are now opposing the Kremlin’s policy of aggression often show that Muscovy is the younger sister of the Kyivan Rus’ – the real and spiritual base of modern Ukraine. Plokhy does not exclude the possibility of searching for bonds between today’s Moscow and medieval Kyiv since, as he explains, the link between those two political spots was a consequence of a particular ruler’s strategy. Nevertheless, the scholar is strongly convinced that historical sources confirm one undisputed thesis: the roots of Ukrainian history can be found directly in their own modern capital – Kyiv.

As a result of the dominance of the Russian narrative, the stereotype of Ukraine divided between its east and west – with a clear demarcation line somewhere near Kyiv which is reinforced by religious and linguistic differences – has re-emerged today in the public discourse. Trying to properly approach this issue, Plokhy takes us back to the time of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the unsuccessful battle undertaken by the emerging Ukrainian elite in the mid-16th century to establish itself as a political nation and community equal to the Polish and Lithuanian nobles. Plokhy regards the 1569 Union of Lublin (which established the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) as a dramatic loss on the Ukrainian side. From the Polish perspective the Ukrainians then became a second-class category of inhabitants in the Commonwealth. Further, the Union led to the consolidation of the Cossack movement and its subsequent alliance with the Orthodox Church, standing naturally in opposition to the Polish Roman-Catholic majority. Thus, the “Great Revolt” of 1648, which was the Cossack uprising led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky against the Commonwealth, was a crucial step in cutting ties from Warsaw and commencing a flirtatious political game with Moscow.

The 1654 Treaty of Pereyaslav concluded, upon Khmelnytsky’s initiative, with the Russian Tsar Alexey I. The aim of the treaty was to guarantee Russian political and military protection. This eventually led to the practical subordination of the Cossack Hetmanate to the Tsardom. Plokhy emphasizes that these events were also exploited by Soviet propaganda to underline the “brotherhood” between the Ukrainian and Russian nations. Here it is sufficient to mention Nikita Khrushchev’s “gift” to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and the transfer of Crimea from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954 on the 300th anniversary of the Pereyaslav agreement.

Khmelnytsky’s efforts to seek stronger political support in fact froze the division of Ukrainian territory for more than 300 years. The country’s west – under Polish, Habsburg and again (after 1918) Polish rule – and its east, which belonged to the Russian world, met again in the Soviet Union after the Second World War. At that time, however, there was no will to differentiate Ukrainians from other “Soviet nations”. Thus, to uncover the “Ukrainian element” Plokhy tries to shed more light on the main characters that contributed to crafting the Ukrainian spirit throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. He points to such notable figures as Taras Shevchenko or Mykhailo Hrushevskyi who played important roles in the national revival of Ukrainians. Plokhy ends his book with a description of the EuroMaidan revolution, which might be seen as the last step of the Ukrainian national revival. This uprising, however, has led to the formation not only of an ethnic but also a political nation. National heroes from the past – such as Shevchenko – were reborn in people’s hearts during the cold winter of 2013 and 2014. Thus the ouster of Yanukovych, Plokhy believes, shall be seen as a new beginning on the banks of the Dnieper River as well as the erosion of the idea of Ukraine as a key to the Russkiy Mir. The question remains however whether the loss of Crimea and the ongoing armed conflict in Donbas is the “price of freedom”? Plokhy does not answer this question. Instead he emphasises the value of the Revolution of Dignity as a significant step on the path to disclose the truth and seek justice for historical abuses and atrocities.

Plokhy’s The Gates of Europe. A History of Ukraine can be read and understood in two different ways. First, it can be taken in as a classic textbook of Ukrainian history which offers a unique possibility of getting acquainted with over a thousand years of the Ukrainian nation. Today, however, I would suggest reading this book somewhat differently. Plokhy’s book allows us to understand the contemporary challenges and dilemmas that Ukrainians face in the light of their largely complicated history; torn between the east and the west, between freedom and subordination. As a result, Ukraine has become a real and spiritual gate to and for Europe. It is necessary not to close this gate for Ukrainians today who are still in the process of searching for their own roots and formulating a shared national identity.

Plokhy makes it clear: “[the] historical contextualisation of the current crisis suggests that Ukraine’s desperate attempts to free itself from the suffocating embrace of its former master have a much greater chance of success with strong international support”. If Europe cannot manage to find a way to effectively help Ukrainians, the first step should be at least to not hinder their expectations and aspirations.

Tomasz Lachowski is a Polish journalist and a PhD candidate at the Department of International Law and International Relations (Faculty of Law and Administration), University of Łódź.