From North African Communist to Bold Friend of Hungary

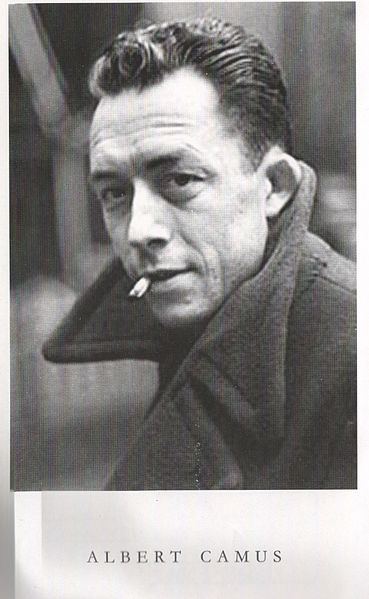

November 7th marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of the great French-Algerian writer Albert Camus (1913-1960), one of the past century’s most influential European thinkers.

November 6, 2013 -

Filip Mazurczak

-

Articles and Commentary

369px-A._Camus.jpg

Truly a Renaissance man, Camus was a novelist, essayist, existentialist philosopher (although he disdained the label), wild soccer enthusiast and skilful womaniser. Although many tomes have been written about Camus’ life and thought, few remember his evolution from being a card-carrying Communist to being a solitary voice among West European intellectuals in defending the oppressed nations behind the Iron Curtain.

In the 20th century, Communism had an almost irresistible appeal to West European and, to a lesser degree, American intellectuals. Pablo Picasso, Jose Saramago, Jean-Paul Sartre and Jurgen Habermas all, at various points in their lives, became infatuated with the ideals of Marxism-Leninism. This trend was not only limited to intellectuals, but to many less serious public figures: in the 1960s, Jane Fonda publicly supported the North Vietnamese during the American military involvement in Indochina. Meanwhile, intellectuals in the Third World, especially in Latin America, who witnessed a dramatic disparity between the rich and poor, also turned to Communism. Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Pablo Neruda, Nelson Mandela and Diego Rivera are all emblematic of this trend.

However, relatively few among these intellectuals ultimately broke with Communism. Sartre considered himself a Maoist all his life, and he called the Communist psychopath Che Guevara – responsible for the executions of thousands of aristocrats, clergymen, homosexuals, blacks and others seen as “undesirable” by Castro’s regime and the imprisonment of thousands more – “not only an intellectual but also the most complete human being of our age”. Although Mao was the 20th century’s biggest butcher in absolute numbers – killing up to 70 million, thus surpassing Hitler and Stalin greatly – Maoism still holds some attraction in certain Left Bank Parisian cafes. Alan Badiou, one of France’s most popular contemporary philosophers, for instance, is an avowed Marxist. Meanwhile, Mandela continues to enjoy a close friendship with Communist despot Fidel Castro, who remains the world’s longest-reigning dictator.

Camus in this regard is an exception. Given his background, his initial attraction to Communism seems logical. However, a common thread throughout his life’s works is rebellion against nihilism, against the absurdity of having a meaningless destiny in a godless universe, and against political oppression. It is this rebellious spirit that first led Camus to become attracted to Communism, and that later made him an outspoken defender of the East European nations shackled by the tyranny of the hammer and sickle.

The son of settlers from France and Spain, Camus was born and raised in a poor working-class district of Mondovi in Algeria, then a French colony. However, it was not so much the economic circumstances in which Camus came of age that made him a Communist. Although of European ethnic background, Camus abhorred the French colonial exploitation of the Maghreb and joined the Algerian Communist Party in 1936. The Communists were at the forefront of the struggle for national liberation in Algeria. Quickly thereafter, however, Camus was expelled from the party for his unorthodox views.

Nonetheless, Camus was a “fellow traveller” of sorts of the communists later. Camus spent the Second World War in Nazi-occupied France, and he associated himself with the French Communists as they were at the forefront of the struggle against the occupying Germans.

By the 1950s, however, Camus became disillusioned with Communism. Meanwhile, Jean-Paul Sartre, another distinguished citizen of France’s Republic of Letters and a long-time friend and kindred spirit of Camus, stayed a dogmatic Communist, as mentioned above. This was one of the reasons why Camus and Sartre’s ways parted. Afterwards, their relationship mostly was limited to sharp barbs addressed at each other published in French newspapers.

If his concern for Arabs strangled by selfish European interests and nauseous reaction towards Fascist imperialism led him to Communism, it was Stalinism and empathy towards suffering East Europeans that made Camus an anti-Communist.

In 1953 construction workers in East Berlin began striking, and eventually both workers and intellectuals in hundreds of East German towns began protesting against the German Democratic Republic. This led to a Soviet invasion. Until the peace marches in 1989 in Leipzig and other cities (as Princeton historian Stephen Kotkin notes, the GDR never had a large dissident movement and its anti-regime opposition, along with that of Romania, was the smallest in the former Eastern Bloc), this was the largest anti-government demonstration in the GDR. This episode led to Camus’ first public denunciation of Soviet viciousness. Camus led the vocal protests against the Soviet military intervention among the French anarchist movement, with which he was loosely allied at the time.

However, it was the brutally crushed Hungarian Revolution of 1956 that showed Camus the anti-Soviet defender of freedom at his finest. On the first anniversary of the fated revolt, Camus gave a speech entitled “The Blood of the Hungarians” in which he praised and encouraged the courageous Hungarian nation: “I hope with all my heart that the silent resistance of the people of Hungary will endure, will grow stronger, and, reinforced by all the voices which we can raise on their behalf, will induce unanimous international opinion to boycott their oppressors. And if world opinion is too feeble or egoistical to do justice to a martyred people, and if our voices also are too weak, I hope that Hungary’s resistance will endure until the counterrevolutionary state collapses everywhere in the East under the weight of its lies and contradictions.”

Camus also deplored the West for turning a blind eye towards Hungary: “[F]or this lesson [of freedom] to get through and convince those in the West who shut their eyes and ears, it was necessary, and it can be no comfort to us, for the people of Hungary to shed so much blood which is already drying in our memories. In Europe’s isolation today, we have only one way of being true to Hungary, and that is never to betray, among ourselves and everywhere, what the Hungarian heroes died for, never to condone, among ourselves and everywhere, even indirectly, those who killed them.”

Unfortunately, the strong reaction of the West to the Hungarian Revolution was largely symbolic. For example, three West European countries boycotted the Olympics (which were in… Australia, not anywhere in the East Bloc; therefore, this had marginal significance even from a symbolic point of view) to protest the Soviet invasion. In his monumental work Failed Illusions, Hungarian émigré (and veteran of the Revolution) and Johns Hopkins University political scientist Charles Gati notes that the United States’ support to Hungary was limited to encouraging Radio Free Europe and Voice of America broadcasts, while Washington was reluctant to send concrete aid the Magyar freedom fighters. Even worse, West Germany’s foreign minister actually discouraged East Europeans from resisting Soviet rule in order to not provoke violence from the Kremlin.

While nowadays the Soviet invasion of Hungary is widely seen as a textbook example of Communist barbarism (and the event gave Khrushchev the well-deserved nickname “the Butcher of Budapest”), many Western intellectuals declined to condemn the massacre. Giorgio Napolitano – now Italy’s 88-year-old president who since has become an apostate of Communism; then a prominent member of Italy’s Communist Party – then wrote an article in the country’s Communist paper denouncing the Hungarians as “thugs” and American imperialist counterrevolutionary agents.

With the possible exception of Pope Pius XII, who devoted an entire encyclical to Hungary’s struggle for freedom and who was a protector of Hungary’s bold primate Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty, a fighter of both fascism and Communism, arguably no one else in the West defended Hungary as vocally, explicitly, and uncompromisingly as Camus.

The 100th anniversary of Camus’ birth is a perfect opportunity for readers of New Eastern Europe to remember this brave intellectual, who at the same time represented both Western Europe and the Third World, who ultimately resisted the intellectual fashions of his age and defended East Europeans from Stalinism. His was a prophetic voice. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Camus realised that rebellion and the struggle for the liberation of captive nations leads to anti-Communism.

Filip Mazurczak studied history and Spanish literature at Creighton University and international relations at The George Washington University. He has interned at The United States Congress and The American Enterprise Institute, and his articles have appeared in publications such as First Things, Tygodnik Powszechny, and Katolicki Miesięcznik “LIST”.