Without James Bond: Women, money and power

April 30, 2013 -

Aurore Guieu

-

Articles and Commentary

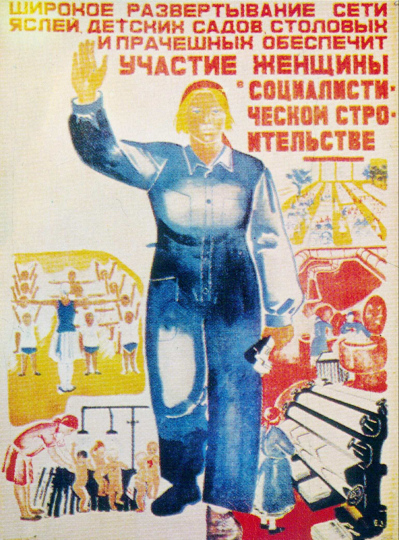

Soviet_feminism.jpg

A 2012 historical study covering 85 per cent of the world’s population has proved that women’s organisations were crucial for policy change towards more equal societies; a role that has already been acknowledged by the United Nations in many documents, notably through its Commission on the Status of Women. Yet, the recent economic crisis has led to the financial uncertainty of NGOs and women’s organisations, and Central Europe is no exception to the rule.

If civil societies in the region of Central Europe can be vivid and politicised, as the Visegrad Revue recently showed, it would seem that feminism remains a “dirty word” and government policies still largely ignore the issue of women’s rights and equality in the region. However, a greater empowerment of women’s organisations would allow for an improvement of these rights at a moment when they face both traditional challenges and the challenges associated with the economic crisis.

A Crisis? Where?

Facing crises is nothing new to Central European women. The economic transitions may have also left a bitter taste to many men, but as Amélie Bonnet, a French researcher, at the 2012 V4SciencesPo Conference on Women and Feminism(s) in the Visegrad region noted: “Because the gender roles had not changed, the new requirements [for example at work] were likely to have more adverse effects on women.” Yet, the crisis shook Central Europe at a time when the region was supposed to be coming out of the transition from the communist system.

The general ignorance of women’s economic issues by local governments and the media makes it hard to quantify the full impact of the crisis on women in the region. The Network of East-West Women, based in Poland, assessed the national statistical methods and found that data on the labour market or poverty are rarely disaggregated by gender. Not documenting a problem is the most certain way to ignore it.

Bits and pieces of information can be found mostly in reports of international organisations and NGOs, and generally do show the consequences that the current crisis has. In 2009, at the outset of the crisis, the European Commission in its report on equality warned that, “the economic slowdown is likely to affect women more than men”. An assumption, however, that does not seem to have obtained much attention since.

Eurostat figures from 2011 show that the gender employment gap is persistent. The difference still went up to 25 per cent in Poland and Slovakia, and Central European women are still earning on average only 80 per cent of their male colleagues’ salaries today. Consequently, entering retirement with 20 per cent lower pensions, elderly women are particularly at risk of poverty. In fact, the direct effect of the crisis on public services in the region affects women both as employees and beneficiaries of state aid. As many of these employees are women, they are directly hit by staff reductions. But they also are the ones who substitute for the state when childcare or elderly facilities are closed down.

As Slovakian expert Zora Bútorová noted at the V4SciencesPo conference: “Women are first and foremost seen as those taking care of the household.” In 2011, according to the EC pension study, part-time jobs in the whole of the V4 region have systematically been occupied by at least twice more women than men. Meaning, of course, lower benefits and pensions. An Oxfam and European Women’s Lobby (EWL) survey shows that women in the region express more worries than men about the current crisis, anticipating notably future financial difficulties and paying more attention to variations in food prices. These perceptions prove, if necessary, the preponderant role that women still play in family care.

Indeed, policy responses in the region have rather been on the austerity side. Austerity packages included notably cuts in pension and public sector expenses as well as the suppression of public transport or energy subsidies, as adopted in Hungary. A collective of European and international women's organisations emphasised that this increase in costs for households is mainly borne by women. Costly transportation, for example, deters young mothers in rural areas from signing children up for childcare and therefore forces them to stay at home. Central European women also paid the price for austerity measures adopted in neighbouring Western European countries. Public financial support to care-related activities decreased in Austria, threatening the jobs of approximately 25,000 Slovaks working for Austrian families. Czechs and Poles faced similar difficulties, although to a lesser extent, in Germany.

The public policy response has yet to systematically address the challenges faced by women. Rather, women's organisations are the ones who have specifically and consistently tackled these questions. One example is the Karat Coalition, a network of women's rights organisations in Central Europe, which advocates for regional economic literacy programmes, providing women with the basic knowledge of economics. The 2012 AWID (Association for Women in Development) Forum in Istanbul brought together different women’s organisations dedicated to “transforming economic power to advance women's rights and justice”. But the question still remains, as these organisations replace the state in helping women, is it enough to make significant strides to reverse the trends?

Funding and policy challenges

As noted above, precise data on women’s organisations is very difficult to obtain. Because of their diversity, such organisations are difficult to track across the region and assess. Many of these organisations are grassroots movements. Their limited resources often restrain their size and visibility.

The data does show, however, that the financial condition of these groups, which was hardly solid before the crisis, has drastically worsened over the past five years. In some cases, public and private funding fell by up to 40 per cent in the region. A 2010 regional strategy meeting organised by AWID and the International Network of Women's Funds (INWF) revealed that 61 per cent of women's organisations in the region currently have a budget of less than 50,000 US dollars per year. As budgets shrink, the services they provide become more limited.

The crisis has impacted financial resources in diverse ways. On average, American and European foundations saw a decrease of 15 to 22 per cent of their assets in 2008-2009, which forced many to withdraw from the non-governmental sector. A report on European foundations funding for women shows that although many foundations in Central Europe express a strong interest in the area of civil society, justice and human rights, women’s organisations are far from being their main beneficiaries. They mainly receive money from specialised women’s funds, which are not among the biggest donors and therefore can only provide small and limited grants. The Slovak-Czech Women's Fund has only been able to distribute 431,000 euros to 173 organisations over the past five years, which amounts to an average grant of 2,500 euros. Arguably, such grants guarantee a consistent and long-term impact.

Public funding followed the same path, with the OECD showing that Official Development Assistance funds in Europe, of which already only 12 per cent was used specifically for women’s rights, have fallen by 40 per cent between 2008 and 2010.

Back on the radar

How to put women on the “crisis agenda” is not only a Central European issue. At the EU level, the debates have also rarely touched the matter. A recent assessment of European economic strategies undertaken by the European Commission’s department for citizens' rights and constitutional affairs, unveiled that gender equality was “surprisingly infrequent” with no mention made of national and regional women’s organisations. On the V4 regional scale, it only means women’s voices are barely heard and their chances to influence strategic policies appear to be extremely limited.

Women's movements are just like any other civil society organisation: they need resources to sustain their activities, especially at a moment when the demand for their services is on the rise. However, not only did the crisis worsen the economic situation of women and lower the possibilities for funding of women’s organisations, but recent political responses have not yet fully taken into account the gender dimension. Thus, women's organisations are currently fighting on many fronts with fewer resources, while data shows they have the potential to play a major role in the resolution of the crisis at a regional level. “Where there is money, there is power,” declared Kinga Lohmann, head of the Karat Coalition. Let's also just bring women into that equation.

Aurore Guieu is currently working as a Junior Researcher for the International Centre for Reproductive Health (ICRH), Belgium. She obtained a MA in European Affairs from SciencesPo Paris, France, and also studied at the Metropolitan University in the Czech Republic. She has been General Secretary for the V4SciencesPo association since 2011.

The V4SciencesPo association aims at strengthening the links between SciencesPo, one of France's major universities in political and social sciences, and the Visegrad 4 countries. Through conferences, roundtables, and social events, the association seeks to gather V4 and French students and to make Central Europe more visible in France. This article is linked to the conference "Women, Feminism(s) and Gender in the V4 Countries", which was organised by the association on September 18th 2012, in Paris. For more information, please visit www.facebook.com/v4sciencespo and www.v4sciencespo.eu (currently under construction).