The Heart of the Cold War

January 31, 2013 -

Josh Black

-

Bez kategorii

9780143122159.jpg

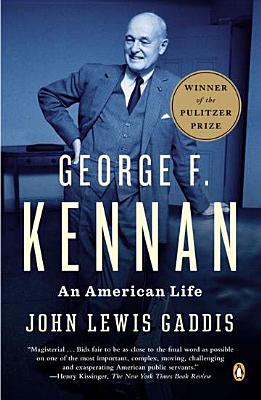

A review of George F. Kennan: An American Life. By: John Lewis Gaddis. Publisher: Penguin Books, London, 2012.

George Frost Kennan, America’s most influential sovietologist and author of one of the fundamentals of US Cold War strategy, has a considerable claim to fame. According to no less an authority than Henry Kissinger, “No other foreign service officer ever shaped American foreign policy so decisively or did so much to define the broader public debate over America’s world role.”

The need for a definitive biography is therefore obvious, and although Kennan's archives and prize-winning autobiographies have spawned many progeny, the access granted for John Lewis Gaddis’ book was remarkable.

Gaddis waited nearly 30 years until the death of his subject (who died aged 101 in 2005) and then spent six years writing his biography of Kennan; but it has been worth the wait. Scores of personal interviews, and sources as obscure as Kennan’s dream diaries have been utilised to construct a picture of the man behind the lectern. Unsurprisingly, Gaddis’ mastery of the twists and turns of the Cold War also go a long way towards explaining Kennan’s apparent volatility.

Kennan’s view of the world was complex to the point of contradiction. His training for policy planning was rooted in empirical thinking, although he thought primarily in terms of historical ideals, especially once freed from the employment of the State Department. Communism, Kennan could tell from his time in Moscow, was an unnatural phenomenon that would eventually overstretch itself. As a governing philosophy, it made harmonious diplomatic relations between the USSR and US impossible, but its coexistence alongside capitalist systems was plausible within distinct spheres of interest.

Out of this situation came the policy with which Kennan came to be most closely associated, yet always felt had been represented. As Gaddis is at pains to point out, “containment” was never the “strategic monstrosity” that Walter Lippmann, an advocate of strategic minimalism, painted it to be. Kennan initially, although with some exceptions, opposed the extension of the Truman Doctrine to military confrontation. His suggestion of extending Marshall Aid to the Eastern Bloc – thereby forcing Stalin explicitly to deny Czechoslovakia the chance of financial independence from the USSR – provided a perfect example of his tactical nous.

The fear of nuclear war, which Kennan frequently described as doubtful, compelled much of his thinking nonetheless. His resignation of Central and Eastern European states to what he considered the more vital influence of Soviet security interests saw Kennan out of touch with the growing support for "liberation" amongst Republican circles and makes him appear cynical to modern eyes. Despite flirting with a political career, he was always hopeless at understanding the constituencies American politicians played to.

Kennan’s lack of political empathy and his tendency to shy away from conflicts led to dramatic shifts in policy. After initially supporting the invasions of both Korea and Vietnam he ended up espousing withdrawal. He was in favour of supporting communist forces in China as a means of dividing the world communist movement even before Mao Zedong’s 1949 victory, yet complained to Kissinger in 1969 that diplomatic recognition would risk a war with the USSR. Kennan remained in favour of unilateral disarmament, yet regarded both détente and Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties hopeless.

These inconstancies in Kennan’s proposals frequently led contemporaries to diminish his qualities as a thinker. To Dean Acheson, he had a somewhat mystical view of power-relations, while the consensus on the Committee on Present Danger (a hawkish outfit co-founded by Paul Nitze, who Kennan himself first recruited to the State Department and maintained a friendly rivalry with) was that he was “an impressionist, a poet, not an earthling”.

The thinker and fellow-Russophile Isaiah Berlin acknowledged this description, arguing that “his famous dispatches were concrete, clear, useful and truly important”. It was when Kennan was unleashed that he became “a mystic and a visionary… a kind of Jekyll and Hyde”.

In his short time on the Policy Planning Staff, Kennan’s tactical intelligence was instrumental in gaining the momentum in the Cold War. Yet by 1949, Kennan’s strategic thinking was too bold to influence policymakers. Outside of government he could offer telling insights, but as with his 1957 Reith Lectures, he all too often floundered searching for a strategy that the Cold War really did not demand. He remained something of a minimalist, but frequently sought out the initiative, perhaps lacking faith in the collapse of the Soviet Union, but more likely doubting the resolve of the American people over a long period of time.

It was in part Kennan’s hyperactivity as a lecturer, writer and thinker that allowed him to escape the second contradiction in his life – his dramatic influence on public debate and its sharp contrast in his desultory experience in government. To Gaddis, Kennan’s distinctiveness was that he did not simply sit back and anticipate the future but was constantly reassessing the state of US foreign policy.

By sharing his insight, Kennan informed a whole generation in exactly the way he proposed in the Long Telegram (a 5,500-word telegram outlining a new strategy on how to handle diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union – editor's note). For it was only if “our public is enlightened and if our dealings with Russians are placed entirely on realistic and matter-of-fact basis [sic]” that America could sustain the morale needed to project American values and undermine the survival of communism.

The third and final contradiction in Kennan’s life is expressed in Gaddis’ peculiar choice of subtitle. If Kennan ever truly belonged to America, there is little evidence that he felt it. With his love of Russia (and particularly of Chekov), his Norwegian wife and his distaste for his homeland’s asinine consumerism and democratic politics, Kennan remained a perennial outsider.

Despite Kennan’s efforts to win the Cold War for America, this is no typical, heroic American life in the way one might expect a biography of Kennedy or Andrew Carnegie to be titled, but a testament to the restless, not preordained spirit of the planning of the Cold War.

Josh Black is studying for an MSc in Russian and Eastern European Studies at Oxford University, with a special interest in Russian and Ukrainian politics since 1991.