Much Ado about Minsk, Too Little about Baku

May 7, 2012 -

Jana Kobzova

-

Bez kategorii

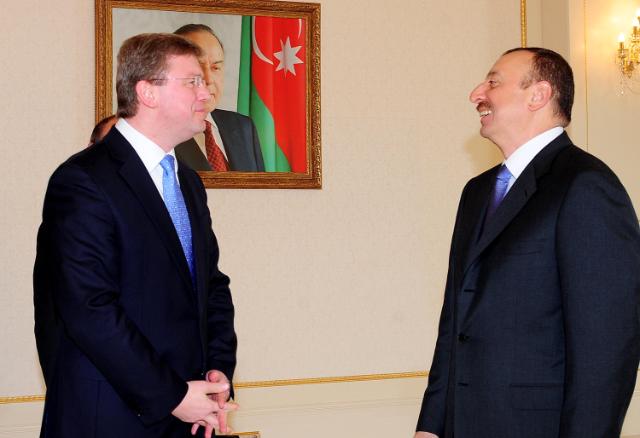

aliyev_Fule.jpg

I recently spent a week in Azerbaijan, talking to local activists, experts and Baku-based diplomats about their views on the worsening human rights situation and what the EU could do about it. Many of these discussions were reminiscent of the tens of debates about yet another autocratic Eastern European country – Belarus. Sadly, most conclusions were similar too. Unless the EU expands its presence in Azerbaijan (and Belarus), it is unlikely to achieve most of its goals.

Of course, the situation in both states is different in a number of ways – Azerbaijan is an oil and gas rich Caspian republic far away from the EU’s borders. Belarus, on the other hand, borders three EU members. The regime in Minsk looks up to Moscow as its key partner and financier; engagement with the EU primarily serves to balance occasional pressure from Russia and gain additional funds. For its part, Baku’s foreign policy pursues a number of vectors: Turkey is without a doubt Azerbaijan’s closest ally but the country also strives to have good relations with Russia, the EU, Iran and the US too. In short, the EU is only one of Azerbaijan's important allies.

Europe's last dictatorships

There is a difference in human rights and liberties between these countries, too – but only in the magnitude of the problem. When it comes to the treatment of political opposition or political prisoners, Azerbaijan often scores as poorly as Belarus and sometimes even worse. Those who put the label “Europe’s last dictatorship” on Lukashenko’s regime but not on that in Baku either think Azerbaijan is not in Europe or simply ignore the facts.

There are ten political prisoners in Belarus today. In Azerbaijan, estimates start at 15. No journalists are currently in jail in Belarus; in Azerbaijan, two journalists have been detained as recently as last month and have been kept incommunicado since then. The last wave of big political repression in Belarus took place almost a year ago – since then one more activists was arrested last autumn and several opposition politicians and independent experts have been prevented from travelling abroad.

The most recent mass arrests in Azerbaijan also happened almost a year ago – but detentions of individuals, smear campaigns targeting journalists and the harassment of NGO activists are becoming an increasingly frequent and common part of lives of those who speak out against the regime not only in Belarus but also in Azerbaijan. Simply put, whether you are a civic activist or an opposition politician, your government will try to make your life miserable both in Belarus and Azerbaijan. But chances are you will be worse off in the latter country.

Different approaches

Yet despite the similarities, the EU has pursued very different approaches towards these two Eastern partners. In the case of Belarus, member states agreed a series of travel bans and targeted economic sanctions on more than two hundred people, including the president himself. With Azerbaijan, on the other hand, the EU actions resemble a conditions-free cooperation. Europeans often issue statements condemning human rights violations and EU leaders usually mention the country's deplorable human rights record when talking to Azerbaijani officials. However, the possibility of linking some of the EU’s assistance to Baku to improvements in democracy or banning those who committed human rights violations from travelling to the EU has not been seriously discussed.

Whether it is because of Azerbaijan’s huge energy resources or other reasons, the EU treats Baku differently than Minsk. This has its value to anyone who follows the long-running argument about whether a “tough” approach on human rights violators, with sanctions and public condemnation (as the EU applies to Belarus) works better than the “sotto voce” philosophy the EU applies to Azerbaijan. The verdict seems to be that neither of the two approaches has delivered the desired effect – improvements in democracy Belarus or Azerbaijan.

Take Belarus. Some argue that the EU’s sanctions policy and the political and economic pressure the EU put on Minsk prompted President Alexander Lukashenko to recently release two political prisoners. But there is another, equally plausible, explanation. The week before Dzmitry Bandarenka and Andrei Sannikau were released, Russia has launched its BPS-2 oil pipeline project to the Baltic Sea. As a result, Belarus will now receive roughly ten million tons less of crude oil annually than before (from 75 million tons in 2010 to 65-67 million tons). In the mid-term, the BPS-2 will reduce the importance of the Druzhba pipeline and thus shave off Belarus’ revenue both from oil transit fees and export of processed oil products. Russia has hit Belarus where it hurts – the fees and sales of oil are important source of income for the country's sclerotic economy. Without them, President Lukashenko's promise of prosperity (without much recognisable economic reform) is in trouble.

Against this background, perhaps another explanation for the release of prisoners, not directly linked to the EU, suggests itself: facing more economic pressure from Moscow, Lukashenko simply returned to his tried and tested tactics of trying to woo the EU to extract more concessions from Russia. By releasing two prisoners – who first had to officially admit their guilt by asking for a presidential pardon – Minsk has improved the prospect of renewed dialogue with Brussels, without giving much in return: the regime is keeping ten more prisoners as hostages. It is not clear whether the EU will re-consider its sanctions now or wait until all remaining prisoners are released. But what is clear is that EU’s policy is not the major factor in Minsk’s calculations: the biggest stick Lukashenko fears is that from the Kremlin.

Missing leverage

In Azerbaijan, the EU has shunned the proposals for political or economic sanctions on the regime. When I asked Baku-based EU diplomats about the possibility of targeted visa bans on those who orchestrated politically-motivated detentions and trials, the response was unanimous: “sanctions won’t work on Azerbaijan: the EU has no leverage in this country”. This narrative – also repeated by the Azerbaijani officials – has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Besides statements on human rights violations, the EU has gradually become more timid about the possibility of holding the regime responsible for the democratic deficit the country has. This is despite the fact that “lack of leverage” talk does not always hold: if Azerbaijan is to diversify its oil-based economy, it is the EU where it will look for technology and know-how. The government is also interested in improving governance – hardly an issue where it can expect much help from Russia or Iran. In short, the EU seems to be giving up even the small leverage it actually has. It is ironic that in one country the EU is surprisingly realistic, almost underestimating its own influence whilst in another it hopes that the visa bans and targeted economic sanctions – hugely important symbolically but hardly a real stick – will prompt the Minsk regime to be nicer.

Neither of the two approaches – tough sanctions or conditions-free engagement – work for the same reason: in both countries, it is only one person – Lukashenko and Ilham Aliyev – who dictate the tone and pace of engagement with the EU, whose own policies are mostly reactive. Except for weak political opposition and fragile civil society, few people in either country feel they have a direct stake in whether the relations with the EU are good or bad. When it comes to linkages in everything from political dialogue or economic integration, education or people-to-people contacts, out of the six Eastern partnership countries, Belarus and Azerbaijan are the two most distant states from the EU. This is despite the fact that the EU is Azerbaijan’s most important trade partner and comes second after Russia for Belarus (in both cases the trade is mostly in energy resources/transit). EU investments in most economic sectors in these countries are minimal (except for Azerbaijan’s energy sector) so few people directly suffer when European small and medium-sized businesses decide to go elsewhere than to Belarus or Azerbaijan.

Simply put, EU’s presence – and thus influence – in both countries does not amount to a substantial leverage. This is the key weakness hampering EU's policy in the Eastern partnership region, as my colleagues Nicu Popescu and Andrew Wilson argued almost a year ago – and it still holds true today. The EU can impose visa bans on Lukashenka’s regime or condemn human rights situation in Azerbaijan – these are very important symbolic steps. But as it is applied today, political conditionality (or lack of thereof in the case of Azerbaijan) is unlikely to force the two regimes to change their ways when it comes to issues such as democratisation of the political system or rule of law: both regimes are keen to keep the dialogue with the EU in the sphere of pure technocracy and economic assistance. Such engagement should be pursued – but alongside that, the EU needs to work more on building its presence and expanding its leverage in these countries by reaching out and building contacts with regular citizens, local business people or grass-roots civic associations.

Today, it is primarily the two presidents who have a direct stake in Azerbaijan's or Belarus's relations with the EU. Only when this changes, will the EU's actions in the two countries have a greater effect on the domestic situation.

Jana Kobzova is a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and the coordinator of its Wider Europe programme.