Belarus: Defining a European policy between the EU’s East and West

February 29, 2012 -

Horia-Victor Lefter

-

Bez kategorii

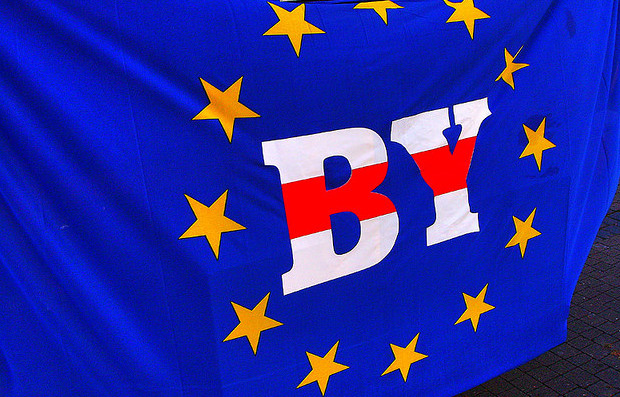

belarus.jpg

After the December 2010 elections and the repression that followed, Belarus and the European Union have fallen once more out of love. In this context of isolation, questions are raised whether the European Union has defined the best strategy towards Belarus. Far from reaching a consensus among the EU's member countries, western Europe seems to have the most ambiguous position.

The European Union (EU) considers itself, according to the 2011 General Report, a major player in all of the world’s regions. However, Belarus has proven to be one of the EU’s biggest challenge. Indeed, none of the EU’s methods has seemed to work when dealing with Belarus’s everlasting president, Alexander Lukashenko. With the Lisbon Treaty in force and an EU ambassador in Minsk, the EU asserts that it is going to proceed to “a major overhaul of the manner in which the European neighbourhood policy is implemented”.

Carrots, sticks and sanctions

After alternating a lack of contacts with sticks and carrots, or just sanctions, Brussels has now, after one “brutally difficult year”, as Hillary Clinton has summed up 2011, added more names to its visa ban black list to the EU. But, since the Belarusian authorities are not interested in both EU accession and democratic reform, EU’s conditionality has only led to a criticising rhetoric from Minsk and a continuous enforcement of the repression.

Besides the bilateral contacts and some European programs and agreements, there are not many links between the EU and Belarus. Until now not even a Joint Provisional Plan has been signed. But thanks to Poland and Sweden, Belarus is at least a member of the Eastern Partnership, though only partially taking into account that no authority was invited to the meeting that is going to take place on 4th March.

Nevertheless, apart from the sanctions to which the EU has returned after the December 2010 elections, Europe has developed a multidimensional strategy that also consists of joining OSCE to its efforts. This European organisation, according to its current chairman, the Irish MFA, “has to keep a channel open to the Belarusian authorities” as it is for now the only one Belarus is a member of.

However, there is no improvement due to a lack a consensus on the strategy to adopt towards Belarus; neither within the civil society community, nor between EU member states. Not only a unanimous vote is required for decisions related to Foreign Affairs, but the 27 States have also different economical interests as well as different relations with Russia. Indeed, the EU members, as the Dutch key player in the Belarusian trade, the French secretive cultural cooperation or, the German “Russia first” rule, in a context of European isolation, have showed a preference for bilateralism.

Meanwhile, it seems that mostly the Central-Eastern members of the EU have understood that the bilateral visits can also be helpful to unfreezing EU-Belarus relations. The Czech Republic’s special envoy currently in mission to Minsk has come “to speak about opportunities for cooperation in the spheres of science, culture, education” in order to help end the stalemate between the EU and Belarus. Moreover, last September’s Second Eastern Partnership Summit which Belarus did not attend because it felt discriminated, is an example of this constant negotiation between the East and West. Thus Warsaw’s demand to invite a Belarusian delegation was accepted by other EU States, mainly from the West, only on the condition that Belarus would be represented just at a ministerial level.

Ineffective measures

EU’s self-esteem blinded itself regarding the real impact of its sanctions. Not only have some analysts considered them more as “restrictive measures” than proper sanctions, but they have also proved that they are ineffective. Indeed, the Belarusians who are affected by the visa bans or the freezing of their assets can benefit from international immunity or have passports issued under alternative names, a KGB favourite method. Last January, the Belarusian Interior Minister travelled to the Lyon headquarters of Interpol because, even though he was on the list of those denied entry in EU, France issued him a visa.

However, the EU and, particularly, western Europe was accused of turning a blind eye to the human rights violations perpetrated in Belarus, taking into account that the EU has a much closer cooperation with countries in the Caucasus which are not much more democratic. The increasing number of declarations condemning the deteriorating situation in Belarus, notably the death penalty, non-transparent elections, political prisoners and unfair trials, despite being perceived as content being singled out by the West as “Europe’s last dictatorship”, it may actually be proof that the EU is not indifferent. Moreover, the Irish Chairman of OSCE has assured that “the situation in Belarus is regularly discussed at the EU Foreign Affairs Council” and that “Ireland identifies and supports with (the sanctions)”.

Whatever may be the method, despite the regret of losing EU and potentially IMF’s financial aid, Belarus will go on accusing Europe of conspiring against its sovereignty and internal affairs and, turning to Russia in order to get the help needed for assuring the regime’s survival. Therefore, one of the measures many are in favour of consists in the abolishment of Schengen visa requirements in order to allow Belarusians to freely travel to EU. This kind of pragmatism on behalf of the EU might help democratising Belarus and also prevent from losing its own sovereignty to Russia.

As EU’s soft power has proven itself of limited reach, analysts as well as some EU countries push the organisation to speak with one voice and impose an economic boycott. While the companies already concerned by the economic sanctions are BelTech Export, BP-Telecom and Sport-Pari, enforcing the economic sanctions might have a worse impact on Belarus than expected, because in 2011 it has reported a very important trade surplus with EU. And this justifies those who advocate in favour of the expansion and the non-politicization of the business and economy cooperation. According to Norway, free trade may “become a channel for (them) to convey critical messages to the Belarusian authorities”. Recently, Slovenia refused to extend to business leaders the sanctions EU has adopted on February 27th. It is considered that an investment of 150 million euro made by oligarch Yuri Chizh, who is close to Alexander Lukashenko, would be behind Slovenia’s attitude.

Expression of solidarity

Despite this, the EU has extended the blacklist to 21 persons from the judicial and police sector and maintained the assets of three companies frozen as well as the prohibition on exports of arms and material for internal repression to Belarus. In consequence, as Lukashenko considered the sanctions “unacceptable”, he requested the departure of the EU and Polish ambassadors “for consultations” with their superiors in Brussels and Warsaw and, recalled its permanent envoys as well. But the EU decided “in an expression of solidarity and unity”, that the ambassadors of all EU member States to be withdrawn for consultations and the Belarusian ambassadors sent back to Minsk.

Nonetheless, Belarus seems to be right, for once, accusing the European authorities of having “no balls”, as Lukashenko has put it. The few decisions this double-faced Union is capable of adopting do not lead to the changes, notably concerning the regime, they were meant for. And what is more, these sanctions are going to be maintained for some time. Indeed they will if the EU waits for Belarus to give it a reason to loosen up. The current events prove the contrary, as Lukashenko was the one who initiated what some call a “diplomatic war”. And, if one cannot come to Europe, it goes to Russia and, when there shall not be any escape, “we (Belarus) will stand here to death, as once in 1941-1945, protecting you, protecting our independence and sovereignty", as Lukashenko has assessed.

Horia-Victor Lefter is currently working as a freelance journalist and expert, writing about Central and Eastern Europe with a particular interest in Belarus, Eastern Partnership, the European identity and human rights. He regularly contributes to several French and English magazines such as The New Federalist, Regard sur l'Est and the Eastbook. He coordinates the publications for the Young European Federalists'special week dedicated to Belarus.