New Year Irresolution

December 20, 2011 -

Andrew Wilson

-

Bez kategorii

ep_s.jpg

It’s customary at this time of year to make predictions for the upcoming year. It’s also customary for those predictions to be wildly inaccurate, but here goes.

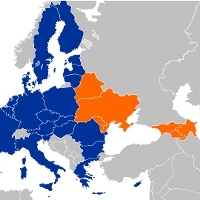

2012 will be a difficult year for almost every country, bar the hard core BRICs. Eastern Europe will be doubly unfortunate to be caught in between continued turmoil in the Euro zone and a Russia struggling to adjust to Putin’s problematic return to the presidency.

The fallout from the EU’s internal problems will be particularly harsh, because it is currently delayed by the opposite – countries both inside the EU and out are clinging to nurse for fear of something worse. Smaller countries like Moldova may still seek shelter from the storm. The mood in larger countries like Ukraine is already Sinn Féin-ist (Irish for “ourselves alone”), which, as Ukraine is not strong enough to tread a genuinely independent path, can only mean worse trouble in the long run.

2012 will also see the continued rise of alternative powers (or props) in the region. China will continue to expand its role, but striking very tough bargains – Beijing is too mercantilist to bail out local powers unless it is in their interest. Turkey has already built up relations with Georgia (Batumi providing a holiday home for Turkish gamblers) as well as Azerbaijan. Ukraine has fantasies about its Black Sea destiny but also faces possible conflict with Ankara as (presumed Russian) local political technologists seem to be behind an attempt to split or radicalise the Crimean Tatar movement.

The idea of using Euro entry as a macroeconomic anchor may already be losing its appeal. Governments will be less able to hide behind it to shield the pain of “internal devaluation” if the big prize suddenly looks tainted. Where the Polish opposition now leads, Latvia and Lithuania could follow. On the other hand, governments like Estonia and Latvia that have already swallowed bitter economic medicine are in much better shape to survive a double-dip.

The other EU anchor, the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA), has been offered to Georgia and Moldova, with the EU confirming the beginning of negotiations at the beginning of December. Unfortunately, the Ukraine process will be in deep limbo at best. The EU side will be in much less of a mood to make quota and other concessions. It will be up to Tbilisi and Chişinău to convince the EU that they deserve to leap-frog over Kyiv rather than Ukraine dragging them down – which will be a tough sell, but one of the EU’s great strengths is bureaucratic inertia, which will hopefully keep the negotiations going.

A multi-level EU will be a hard place for the Eastern Partnership “grey zone” states to find friends. None are potential members of a German-led northern European hard core. The reluctant states, like the UK, Hungary and the Czech Republic, are mainly motivated by defending national sovereignty (which means something different for the Eastern Partnership six), and by seeking allies against Brussels; but it is Brussels, not Member States, that can deliver what EaP states want. Though the UK’s Conservatives may hope to strengthen their links with what they hope is a still Eurosceptic Georgia.

Russia meanwhile seems to be heading towards a hollow Putin victory in March. But even this is only likely to be achieved by more political technology, as the regime struggles to draw the string of protests with cosmetic concessions and slightly more plausible puppet opponents. Other states that are trying to build Putinism-lite, like Ukraine, will find that Putinism is breaking down, or being renegotiated at the very least. They will have to be subtle about control, as in Georgia, or the spotlight will be on them too.

On the other hand, Putin’s launch of the Eurasian Union project last October already gifted Russia’s CIS neighbours a stronger hand. Last week's blog described how Belarus has already exploited Putin’s need for the project to be a success. Now that he is weaker, that need will be more acute.

American voters are used to the phrase “October surprise” before voting in November. A “February surprise” is also entirely possible in Russia, and could easily pit Russia against its neighbours.

As regards to individual countries, Ukraine will continue to make the news for the wrong reasons. It hasn’t built up its economic defences. Almost 5 per cent growth in 2011 sounds good, but the budget and banking sectors are still weak, and structural reforms have been half-hearted. Ukraine is vulnerable to double-dip, though that would at least change the calculus of the current stand-off with the EU.

Ukraine is also heading for a likely PR disaster over the Euro-2012 football finals. The geography was always going to be difficult, but the infrastructure just isn’t there yet. The thought of thousands of drunken English fans in a tent city outside Donetsk doesn’t bear thinking about, even for this patriotic Brit. The Ukrainian police are unlikely to put their notorious corruption on hold for their duration of the tournament. The Yanukovych people don’t know how the international media works. They are sheep, who will all write the same background story about Ukraine while the football is on; which so long as Tymoshenko is in prison will be “Shrek versus the Princess”. The Ukrainian people, on the other hand, will not hear the full story, despite being the government’s main asset for a warm welcome.

The authorities will then gear up to fix the October 2012 parliamentary elections once the football is out of the way. The West should be on the lookout for the next step, which will be the emergence of a new fake opposition.

If Moldova fails again to elect a president in the New Year, then elections are likely in the spring, and the Communists could win. The EU has got used to the Alliance for European Integration’s “success story” in Chişinău; how would it react not just to the Communists but to the return of Vladimir Voronin and a “balanced” foreign policy? That said, the most likely election outcome is another narrow win, with whichever side is victorious still short of the 61 votes to elect a president.

Georgia faces a key election cycle in 2012-13. The regime has yet to show it can compete fairly with Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream project, which was formally launched on 11 December. Ivanishvili has yet to show how that project will engage with the voters and with a system that so obviously opposes him.

Armenia holds elections in May 2012 (parliamentary) and February 2013 (presidential). Azerbaijan’s presidential election is not due until October 2013, but the two are likely to be locked in a dangerous cycle of escalating rhetoric, with Azerbaijan tempted to take advantage of the world’s preoccupations over Nagorno-Karabakh.

And finally, there are the matrioshka elections in South Ossetia and Transnistria. Tbilisi is obviously saying that the chaos in Tskhinvali proves that the local politicians were always a bunch of goons and Russian stooges. However, in neither South Ossetia nor Transnistria did Russia’s favourite win. Even at the micro-level we face a very unpredictable 2012.

Andrew Wilson is a Senior Policy Fellow with the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) and the author of Belarus: The Last European Dictatorship, published by Yale University Press.