Eastern Europe and the People’s Revolutions: Lessons Learned

November 5, 2011 -

Jane Curry

-

Bez kategorii

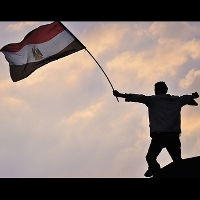

egipt_Jonathan Rashad_s.jpg

With the attention of revolution and democratic transition now on North Africa, it is important to remember the lessons of Eastern Europe from the past 20 years, as well as the fact that its transition has not yet been completed.

The lessons of the Eastern European transitions and People’s Revolutions of the last decade of the twentieth century were forgotten when the Arab Spring blossomed earlier this year. Advocates of Western-style democracy took credit for training the activists which enabled them to get huge numbers of people to the squares and public places. And those that went to the squares and cheered the activists on saw the solution as simply ousting the corrupt leader and his cronies. Despite having its own problems, the West sent in planes to force Libya’s corrupt leader Muammar Qaddafi out, eventually leading to his death. Western advocates, however, have not provided the aid that these newly democratising societies need to meet the demands put forward by the demonstrators. Instead, the follow-up to success has been hard economic times and anger.

Lesson I: It’s the economy!

The most important aspect in ousting the old and creating the new Eastern Europe, and the less successful attempts of the ensuing People’s Revolutions in Ukraine and Georgia, was not so much politics as economics. The collapse of communism in post-Soviet countries like Georgia and Ukraine and the upheaval that followed were triggered by the failure of the socialist regime to provide its main promise: a fair system that would work for the people and that would give them what they needed the most, namely a decent standard of living. In countries where the change happened quickly and smoothly, the elite and those around it came to the understanding that the system could not be sustained as it was. That was exactly why the Hungarians and Poles began negotiations to share or shift the power (and the blame).

Once the old leaders had stepped down, the economy mattered even more. What people listened to the most were simply the promises saying that, “if we win, things will get better”. The freedom of speech and free, fair and competitive elections meant little to people who had to make ends meet. And when life did not get better in some parts of Eastern Europe such as Ukraine, the people yearned for the “good old days”. They voted for populists who attacked the reformers for failing and for being corrupt.

Western money and investment kept the economies of Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic afloat during the transition in the 1990s. But there was a sour taste when that money came with the proviso of making a rapid shift to capitalism. Prices rose and Western products flooded the market. People found themselves poorer than they had been before. In Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, and Romania, this meant that reformed communists came back in new guises only to be replaced by populists who blamed the old system and promised a safety net. These populist calls rang hollow in the Czech Republic where the old state welfare system was not torn down before the capitalist sector was up and running. In Ukraine, the promise to end the country’s major problems of corruption and mismanagement by getting rid of the old leaders fell through immediately after the Orange Revolution.

Lesson II: Home grown protests, learned from surviving repression and shortages, work best!

As the Central and Eastern Europe dissident movements in the 1980s proved, living under communism was good training for working with what you have and rallying people to come to the squares and demonstrate for change. Polish and Czech dissidents would go skiing in the high Tatra Mountains to exchange ideas and information. And while Western advisors assisted all of the opposition movements in their first free elections, the most successful campaign strategies, like blanketing Polish towns and cities with Solidarity posters, were home-grown.

The promoters of Western democracy credit their money and training for getting the opposition into power in the “revolutions” that have taken place in Serbia, Georgia, and Ukraine this decade. However the reality is that youth group leaders used the Internet themselves to research and find out about how to organise non-violent protests.

The masses that poured into the public squares were not there to make fun of the old regime or opposition campaigns. They came because they were angry. And once it became clear that no one was stopping them, the numbers grew. The demonstrators quickly used the skills they had learned by living “around the system” and making things work. The demonstrators knew how to get food and work together, just as the demonstrators on Tahrir Square and elsewhere in the Middle East did.

What those in the West, who cheered them on, forgot was that working together against the system does not automatically build a civil society able to work within the system. Experience in Central and Eastern Europe has already showed us that a lot of time and effort is needed for a strong civil society to develop as its leaders neither emerge from within the activist groups that the promoters of Western democracy have trained, nor from the crowds of demonstrators who have gathered in the public places.

Lesson III: Western engagement before and after is what counts!

The West is still a vital symbol for post-Soviet transitions and the new Eastern Europe. The Western media show these societies what they could become and make people ask questions such as, “why not me?” Western engagement with authoritarian leaders makes them unwilling to bite the hand that gives them credibility, aid, and trade. In addition to this, Western training and travel “corrupts” people around the leaders who are responsible for making policy, administering it, and guarding the system. Those who have been trained in prosperous democracies see things differently. That is why, like the guard who let out the demonstrators who swept into the Georgian parliament forcing out the old leader, Eduard Shevardnadzee, they can say: “Your secret service has taught me that it was not my job to harass citizens. So, I opened the door”.

New leaders desperately need the aid, trade and training that the West offers. After all it was this which has contributed significantly to the success of these transitions in the Central and Eastern Europe countries. Serbia was close enough to Europe, despite its bulldozer revolution which pushed Slobodan Milosevic out, that its people could live in the faint hope of “returning to Europe”. The money that flooded into Georgia from George Soros and US government agencies in the aftermath of the Rose Revolution in 2003 gave the Saakashvilli leadership the resources to attack corruption and make a show of change. However, even this money came with so few strings attached that the new leaders did not make real democratic reforms. It is no wonder that the veneer of Georgia’s democracy is thinner today than it was under Shevardnadze. In 2004, the Orange Revolution floundered in Ukraine. However, the promises and popular hopes that it raised happened too fast. Time and again, the Western money spent on rebuilding transitioning countries has proved to be not up to the task.

Lesson learned?

The ultimate lesson is obvious. It is easy to demonstrate in the streets, but building a new system out of the ashes of the old one is hard. By forgetting the lessons of 1989 and the post-Soviet revolutions, we have left the “successes” of Egypt and Tunisia to turn on themselves as people wonder how much freedom is worth when there is no food to eat. This is the reason why the models of aid and support, which are necessary after revolutions, need to be remembered now.

Jane Curry is a professor of political science at Santa Clara University (United States). She has written widely on communist and post-communist opposition movements and transitions in books such as Poland’s Permanent Revolution. She is completing a book on the People’s Revolutions based on interviews funded by the United States Institute of Peace.