The end of Ukraine’s post-Soviet era

Irrespective of the many challenges ahead, Ukraine seems to be on the verge of ending the post-Soviet chapter of its history.

August 13, 2019 -

Taras Kuzio

-

Articles and Commentary

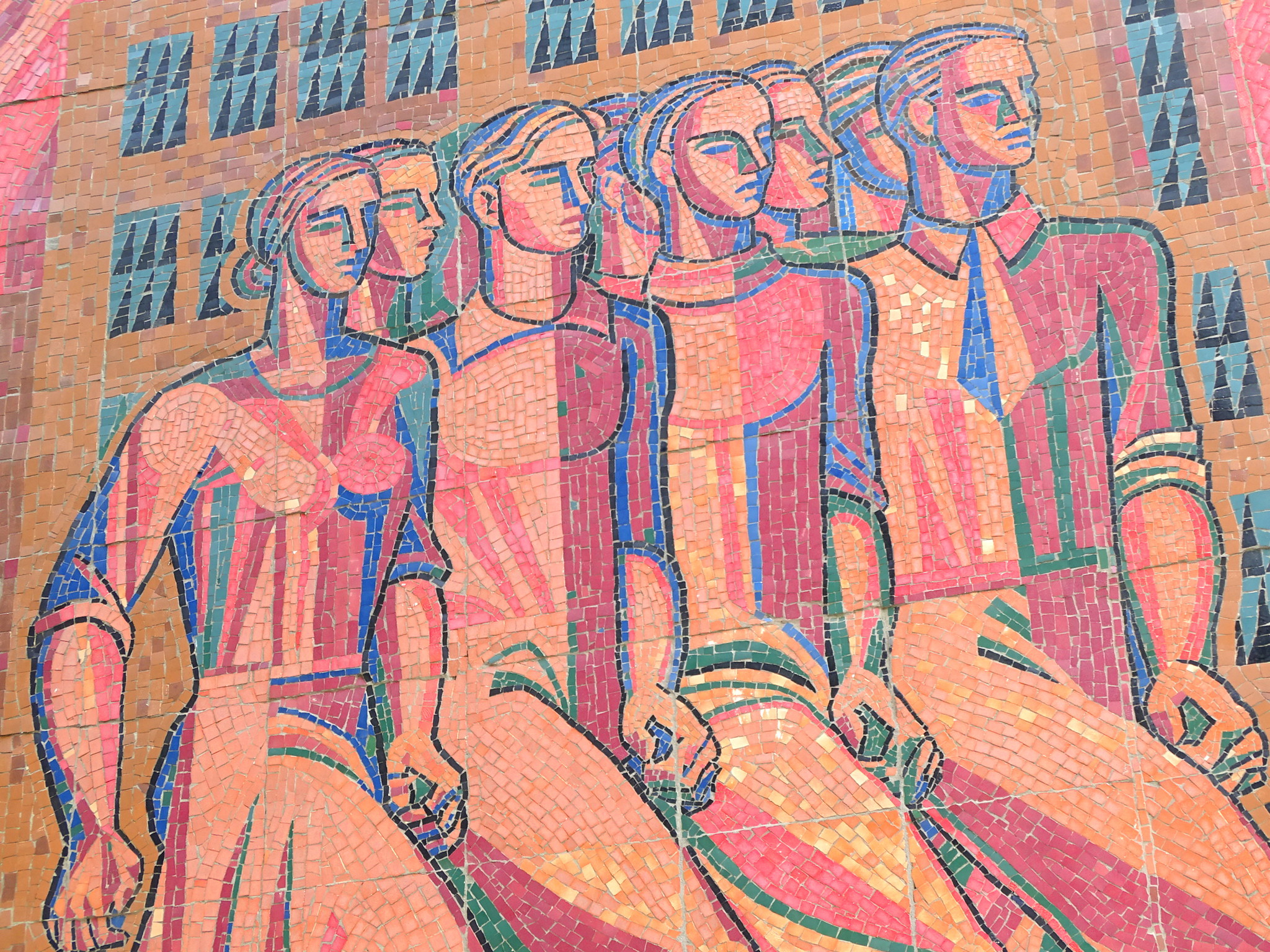

Mosaic from the Soviet era in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Photo: Adam Jones (cc) flickr.com

The election of Volodymyr Zelenskyy and the Servant of the People party by overwhelming landslides in the April and July presidential and pre-term parliamentary elections represent the end of Ukraine’s ‘post-Soviet transition’ nearly three decades after the USSR disintegrated. Zelenskyy and his presidential team and parliamentary faction are not connected to the 1990s and their rise to power represents a historical juncture between the country’s Soviet past and European future. The vote for Zelenskyy was more than a vote against Poroshenko; it was a vote against the entire establishment.

The Orange and Euromaidan Revolutions were undoubtedly stepping stones towards this historical juncture. In 2004, central Ukraine joined forces with the western region to elect Viktor Yushchenko as president. A decade later, the Euromaidan Revolution was more broadly based throughout the entire country; following the revolution’s success and Russia’s military aggression, its influences spread to the east and south.

Another key indicator that 2019 was a historical juncture was the collapse of the pro-Russian camp and Ukraine’s pro-Russia orientation. In the presidential elections, Opposition Platform candidate Yuriy Boyko came in fourth place and therefore did not enter the second round. In the pre-term parliamentary elections, ten pro-European forces received 81 per cent of the vote within the proportional aspect while two pro-Russian forces received only 17 per cent. With pro-Russian forces divided and 16 per cent of voters unable to participate because they live in occupied territories, it became impossible for pro-Russian forces to come to power.

Ukraine’s ‘east’ has been shrinking since 2014 from nine Russian-speaking eastern-southern regions and Crimea to two regions in the Donbas. The 2019 elections showed that even in the Donbas, a region dominated by the Party of Regions and Communists prior to 2014, pro-Russian forces came under threat from three pro-Western parties who receiving a combined 37 per cent of the vote. In the presidential elections, pro-Russian candidate Yyuriy Boyko did not monopolise the Donbas where he received 44 per cent and 36.9 per cent in Luhansk and Donetsk regions respectively.

2019 was also a defeat for liberal ‘Euro-optimists’ who entered parliament five years ago within the Poroshenko bloc or other pro-Western forces and then became dissidents. By focusing on their self-image, they ignored the chance to build a new united liberal force. Svyatoslav Vakarchuk’s vacillation over whether he would stand in the presidential election also hurt him politically, and his hastily-created Holos (Voice) party came in last with only 5.8 per cent, barely scraping over the threshold to enter parliament.

President Zelenskyy and Servant of the People have taken the niche previously occupied by three groups in Ukrainian politics. First, the liberals that Vakarchuk could have won if he had decided to stand in the fall of 2018. Second, they received support from some national democrats who voted for Poroshenko and Arseniy Yatsenyuk in 2014 but had become disillusioned. Third, they took electoral territory previously occupied by populists.

President Zelenskyy and Servant of the People represent a very broad coalition which may find difficulty in remaining united. A similarly broad coalition of reformers (Viktor Yushchenko), populists (Yulia Tymoshenko), socialists (Oleksandr Moroz), and centrist industrialists and oligarchs (Anatoliy Kinakh) that came to power during the Orange Revolution disintegrated in 2006 after only a year. If the Servant of the People coalition does split, these different branches could become the kernels of new and genuinely non-Soviet political parties; indeed, some of these future dissidents would inevitably unite with Vakarchuk’s Holos.

Presidential candidate Zelenskyy made many promises during both elections and it will be difficult to satisfy such high levels of public optimism, a fact which unnerves Ukraine’s intellectual elites. ‘What concerns me [is the] optimism,’ Mykhailo Minakov, the Kennan Institute’s Senior Advisor on Ukraine, said in a briefing on Ukraine’s elections. ‘So far, we have an unprecedented level of optimism among the Ukrainian population about the development of [the] country. We’ve never had it like this, according to the sociological polls, in all the 28 years or from [the] the early 1990s… Which makes it a very big responsibility of the current winners, of President Zelenskyy and his party, not to spoil the challenge.’

The Ukrainian public has similarly high levels of expectations from President Zelenskyy as the people did with Poroshenko after the Euromaidan Revolution. Zelenskyy won every region except Lviv while Poroshenko won every Ukrainian region. Unlike Yushchenko, President Zelenskyy cannot make any excuses for being unable to implement policies because he will control parliament and the government.

Poroshenko and Zelenskyy both received majorities throughout Ukraine and if Zelenskyy’s popularity will fall it will does so nationally, as was the case with Poroshenko. Prior to 2014, presidents such as Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych only received votes in one half of the country. Concord Capital analyst Zenon Zawada believes ‘optimism will evaporate by the year-end.’

If President Zelenskyy tries to change or reverse de-communization and Ukraine’s language law or language quotas on television and radio, his popularity will quickly slump. There are two areas that could provoke a third Maidan, and these are capitulation to Russia in return for peace in the Donbas region and undermining Ukrainian identity. In September of 2015, when parliament was under Western pressure and discussing changing the constitution to give ‘special status’ to the DNR and LNR, a riot by nationalists and war veterans ended with grenades being thrown and three national guardsmen tragically dying.

How can President Zelenskyy fulfil public optimism? Two of his big promises were to bring peace to the Donbas and fight corruption, and indeed, President Zelenskyy has declared that Ukraine is fighting two wars: one against Russia and the other against corruption.

President Zelenskyy will not have success in bringing peace. He may have a few marginal successes, such as the release of Ukrainian sailors illegally detained by Russia in November of 2018, but he will be unable to end the war. This is because the fundamental cause of the war, namely, that Russians think Ukraine and Ukrainians are fake news, will not change.

Furthermore, 85 per cent of Russians support Crimea’s annexation. Putin says that Crimea is not for negotiation, but a high majority of Ukrainians demand it be returned. Three quarters of Ukrainians do not support recognising Russian control of Crimea in exchange for peace in Donbas.

A further obstacle to ending the war is President Putin’s ‘peace plan,’ propounded by his Ukrainian satellites Viktor Medvedchuk and Yuriy Boyko, which is unpalatable to most Ukrainians. This includes giving ‘special constitutional status’ to the two Russian proxy enclaves of the Donetsk Peoples Republic (DNR) and the Luhansk Peoples Republic (LNR) within a federal Ukraine, as well as replacing NATO and EU membership objectives with neutrality. The only political force that supports what many Ukrainians see as capitulation is Medvedchuk and Boyko’s Opposition Platform.

The way forward

Zelenskyy’s presidency will rise or decline depending on his success or failure in fighting high-level corruption and abuse of office. Poroshenko’s parting gift to President Zelenskyy is an anti-corruption court; therefore, the president cannot blame the traditional scapegoat of a ‘corrupt judiciary’ for keeping senior elites out of jail. Ukrainians are impatient and expect President Zelenskyy to undertake this task within his first year or eighteen months in office. If there are no results, President Zelenskyy’s popularity will quickly fall.

Dealing with corrupt elites and making them accountable to the rule of law also pertains to the vexed question of what policies President Zelenskyy will pursue towards oligarchs. A particularly important signal will be how President Zelenskyy treats oligarch Ihor Kolomoyskyy, with whom he has a long history.

There are three potential paths that President Zelenskyy could take.

The first path would be to make a few reforms but leave the system practically the same.

The second path could be to provide political will for the arrest of some oligarchs; however, if this path is taken, there would be questions over which ones. The easiest and most popular choice would be to go after pro-Russian oligarchs supporting Opposition Platform as part of a national security drive against Medvedchuk’s ownership of four TV channels (NewsOne, 112, ZiK and Inter). Detentions would be accompanied by state nationalisations.

A third path would be to demand oligarchs pay a one-off tax for what they had stolen or obtained cheaply but without any re-nationalization. After paying the one-off tax, oligarchs would be required to play by the rules from then onwards. This path would be difficult to sell to Ukrainians because oligarchs would get to keep what many in the public believe to be stolen property.

One of the most difficult decisions of Zelenskyy’s presidency will be regarding what to do with Kolomoyskyy and whether or not to oppose the oligarch’s attempts to again become the oil baron of Ukraine and to have the biggest bank in Ukraine, Privat Bank, returned to his control. Privat was nationalised in 2016, and a financial audit by the National Bank and Kroll Associates found that 5.5 billion US dollars had been laundered by Kolomoyskyy and his oligarch partners through Privat over the previous decade. There are existing plans to sell four state banks (Oschadbank, Ukreximbank, Ukrgasbank and Privat), which account for 70 per cent of Ukraine’s non-performing loans, and therefore, Kolomoyskyy could seek to retake control of Privat.

Russian chauvinistic attitudes towards Ukraine and Ukrainians, as well as Putin’s inability to compromise and only seek capitulation, preclude Zelenskyy from having success in ending the Donbas war. The fate of Zelenskyy’s presidency will be decided in his successes or failures in the fight against high-level corruption. A major harbinger of President Zelenskyy’s intentions will be whether he remains independent of Kolomoyskyy or serves his interests.

In holding off Russian military aggression and re-building an army, Poroshenko could be compared to Winston Churchill in World War II. Only time will tell if Zelenskyy will take Ukraine into Europe and become Ukraine’s George Washington.

Taras Kuzio is a professor in the Department of Political Science, National University of Kyiv Mohyla Academy and a Non-Resident Fellow, Foreign Policy Institute, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University.