Film as a counternarrative

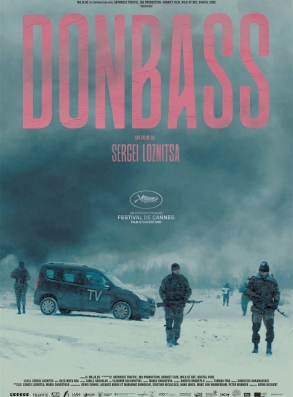

A review of Donbas. A film written and directed by Sergey Loznitsa. Released in Ukraine, October 2018.

It has been nearly five years since the start of hybrid war in Donbas, which has come to resemble something of a frozen conflict in eastern Ukraine. And it is since the separatists, backed by Russian military forces, captured Debaltseve – rather than the Minsk II Accords – that the conflict has evolved into a low-intensity positional fire exchange.

January 2, 2019 -

Jakub Bornio

-

Books and ReviewsIssue 1 2019Magazine

The world seems to have gotten used to and indifferent toward this conflict. Meanwhile, Russia has been pursuing its strategy of waiting, progressively overcoming the diplomatic isolation and hoping for the acceptance of a fait accompli. Although no one expects that the annexation of Crimea would be commonly and officially recognised, a gradual reduction of sanctions would de facto equal the acceptance of the new status quo.

Such voices are constantly heard in some of the European Union member states. So far, it does not look like the Kerch Strait incident will be a real game-changer. On the other hand, the prolonged instability has become a perfect excuse for the post-Euromaidan elite, unable to effectively implement reforms and blaming external factors as the only reason for the dramatic social and economic turbulence in the country. Conventional warfare is not the most important fight anymore; it is a fight for peoples’ hearts and minds that appears to be crucial. Films seem to be one of the most effective tools in this fight.

Hopelessness

In the second half of 2018, the latest film by the Ukrainian filmmaker Sergey Loznitsa was released. Entitled Donbas, it is Loznitsa’s second film about the events in Ukraine, after the documentary Maidan was released in 2014. This time Loznitsa is back not only with his typical silent frames documenting events, but also with a series of short fictionalised stories that depict the ongoing hybrid war, turmoil and chaos in eastern Ukraine. The audience spends most of their time with the inhabitants of Novorossiya (a failed geographical concept which meant to unite pro-Russian people and territory and incite them to break away from Ukraine but instead manifested as the Russian-controlled Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic – editor’s note) and get a full picture of their “normal” everyday life.

The stories take place in the middle of the conflict zone, where the everyday reality is a mixture of manipulation, hatred, indifference and hopelessness. Loznitsa takes the audience to a place where war and death became so common that people care more about broken windows from artillery fire than about the lives of their neighbours who died in the same bombing. The social stratification is more than visible, and it spills out of the screen: the few who are well-to-do and rich enough to survive live alongside the great mass of endangered, ordinary souls. In some scenes, the reality of Novorossiya resembles a comedy, or the surreal world of Monty Python. The grotesque form of some of the stories helps the audience experience the tragedy, suffering, injustice and muck on the screen. However the scenes here, which would normally be hilarious, do not amuse the viewer. They make the viewer contemplate the reality even more deeply.

Propaganda seems to be the main theme of the movie. Its methods and effectiveness are shown to be one of the main causes of the problems and continuous war. The film depicts, although sometimes hyperbolically, how the Russian machinery of propaganda works. And that seems to be the most conspicuous asset of the film. Propaganda is not without impact on the lives of the characters in the film. Those who are indifferent to politics live in Donbas together with those who got stuck in the imaginary reality of a fight with fascists. In the background, a careful viewer will notice a direct reference to RT (formerly known as Russia Today).

The portrait of a poor society – in a material and spiritual way – directed with attention to the finest details does not conceal, however, the main cause of the problems: hybrid warfare and its specifics. We see the “little green men” operating side by side with separatists, the shortcomings of the Ukrainian troops, the functioning of “border zones” and an artillery shootout resulting in a particularly high death toll.

Counterpropaganda

Donbas is filmed like reportage. Following the unfolding plot feels like you are in the middle of the film. The failures of Novorossiya are sometimes intentionally overemphasised and exaggerated. This simplifies the narrative and allows the viewer to understand it clearly, even if a bit unreflectively. On the other hand, simplifications can make effective propaganda. Therefore, basic knowledge of the situation in the region is necessary to follow and comprehend every message invoked.

The documentary, which is a caricature of a para-state, is consistent with the narrative from Kyiv. Ukraine and other Central and Eastern European states are concerned that the West might return to a policy of “business as usual” with Russia. Films like this help to keep the situation in Ukraine vital for the global audience and by doing so also present on the international agenda. Therefore, it becomes an asset of counterpropaganda and a way to present an alternative narrative than the Russian one. Despite the fact that it unveils immoral warfare methods, the “criminal” character of a puppet state, and the shadowy involvement of Russia, it also makes viewers immune to the manipulation and propaganda spread by Russia. Thus, the aim is to win the support of the international public for Ukraine. In this context, it is noteworthy that Donbas was supported by the Ukrainian government and some organisations in Germany, France and the Netherlands.

There is no doubt that propaganda methods evolved simultaneously with the development of technology (and our dependency on it). From whispers and gossip, to posters, leaflets, newspapers, radio, movies, television and the internet – all of them serve as channels for information warfare which target people’s emotions and ways of thinking. Despite the growing importance of online media, however, it is still television which remains one of the most effective tools for propaganda. In addition, cinematography seems to be an active tool that the new “post-Euromaidan” elite are trying to deal with as well. In 2017 Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed a legal amendment to the Law on State Support for Cinematography in Ukraine. While doing so, he emphasised this move as “a key element of decommunisation in culture and cinematography”. What is more, in the context of the ongoing conflict in Donbas, he noted that “We have restricted the broadcast of Russian cinema on our market, for the majority of these products are filled with propaganda of the so-called Russkiy mir (Russian world) that glorifies the aggressor and their security structures.”

Perfect measure

The abovementioned amendment makes it illegal to emit and distribute films that popularise or glorify the “state aggressor” and its activities as well as the ones that justify and recognise the occupation of the territory of Ukraine. After the Euromaidan revolution, the new government associated cinematography with a broader context of decommunisation and propaganda. The main institution responsible for this policy is Derzhkino, the Ukrainian state film agency. The agency was set up in 2005 (just after the Orange Revolution) and maintains the State Registrar of Films and issues the right to distribute and display films in the country. On November 30th 2016, the National Council of Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine announced that, in 2014-2016, Derzhkino refused to register or cancelled rolling licenses for the broadcast of more than 500 films and TV series. This is how the institution became an official “censorship” agency responsible for the propaganda fight in television and cinema. It is noteworthy that Derzhkino was one of the institutions which supported Loznitsa’s film.

Bearing in mind that we now live in the online era, we should ask ourselves whether the power of film is not overrated. It seems that as long as film is a popular form of art and a vital element of pop culture, it remains a perfect measure of propaganda in the fight to persuade audiences, especially when it is able to consolidate national myths, heroes and social perception of historical events in general. In the context of the importance of film in state policy, it is enough to mention the discussion on Polish-Ukrainian relations which took place just after the release of Volhynia, a film directed by Wojciech Smarzowski in 2016.

Donbas is not the only film “in the service of politics”. Ukrainian efforts to create a national identity on the basis of the Holodomor (Great Famine) of the the 1930s were supported by the Canadian melodrama Bitter Harvest, directed by George Mendeluk, who is of Ukrainian descent. In 2017, Kiborgy (Cyborgs: Heroes Never Die), directed by Akhtem Seitablaev, was released. It tells the story of soldiers from volunteer battalions who were defending the ruins of the Donetsk airport, a symbol of the Ukrainian resistance in the conflict in Donbas. Later in 2018, Pozivniy ‘Banderas’ (Call Sign Banderas), a film directed by Zaza Buadze about Ukrainian soldiers in the conflict zone, was released. One year earlier, Buadze released the film Chervonyy (The Red One) about the commander of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) who was sent to a Soviet prison camp. Chervonyy, together with other films like Zhiva (Alive, 2016) by Taras Khymych, promote the cult of the fight for independence which was carried out by UPA. However due to the controversies related to the perception of the UPA, such films are targeted mainly at Ukrainian audiences.

In the fight to express this message to a global audience, Ukraine competes with the Russian narrative. One example is the film Battle for Sevastopol, released just one year after the illegal annexation of Crimea. Even though, the film is of Russian-Ukrainian coproduction (the filming began in 2012), it is coherent with the official narrative of the Kremlin in the way it depicts the Great Patriotic War (the preferred Russian term for what most other countries know as the Second World War) and the story of a female sniper named Lyudmila Pavlichenko. What is most important is how it portrays the Soviet defence of Sevastopol and interprets Sevastopol in the vein by which Putin described it in his infamous Crimea speech on March 18th 2014 as “a legendary city with an outstanding history, a fortress that serves as the birthplace of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, and… is dear to our hearts, symbolising Russian military glory and outstanding valour.”

It seems that, today, states need a film industry that operates as an element of soft power. However such a strategy requires effective institutions operating on the international level as well as talented directors and producers. Sergey Loznitsa with his “piece of art” seems to be one of them. Without judging the intentions of the producers, one should bear in mind that the era of film in the service of politics has not yet finished.

Jakub Bornio is an assistant professor with the Chair of European Studies at the University of Wrocław and has worked as a specialist with the Jan Nowak-Jeziorański College of Eastern Europe in Wrocław.