The Albanian Paintings of Ambassador Calkoen

The English philosopher Francis Bacon once said, “randomness leads to great discoveries.”

February 24, 2015 -

Epidamn Zeqo

-

Books and Reviews

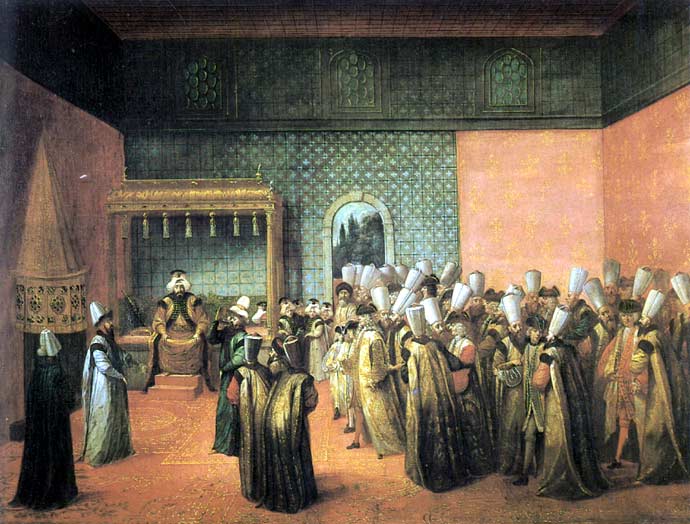

Jean Baptiste Vanmour, "Audience with the Sultan Ahmed III"

Amsterdam is the capital of the art world with renowned names such as the unreachable Rembrandt, van Gogh, and Vermeer or extraordinary philosophers like Spinoza and Erasmus of Rotterdam. The largest and most famous museum in Amsterdam is the Rijksmuseum. Indeed it is a synthesis of the history of the Netherlands, its culture and art and the museum is full of surprises.

Although I had seen the Rijks several times before, I had not yet noticed something that was also connected with the Albanians and Albania. In early January 2015, I noticed a special room named, “Vanmour – The ‘Turkish’ Paintings of Ambassador Cornelis Calkoen.” I had no prior knowledge of Jean Baptiste Vanmour (1671-1737) and Ambassador Cornelis Calkoen (1696-1764).

In the museum’s bookstore I found a book “An Audience with the Sultan” written by Eveline Sint Nikolaas, depicting Calkoen’s diplomatic adventure. In this book I found some very interesting data that I would like to make known to the Albanian and European public.

Cornelis Calkoen was born in 1696. He studied at Leiden and became one of the most educated people of his time. He came from a very rich family that did business in the Levant. He was appointed as Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire and went to Istanbul in September 1726. The Sultan at the time was Ahmed III (1703-1730), who had agreed to welcome the Ambassador in Toptaki Sarayi. The official visit to the Sultan occurred on the August 12th 1727. Jean Baptiste Vanmour painted this visit in a wonderful and typological way.

But who was Vanmour? Vanmour was an excellent, Flemish-French painter, born on January 9th 1671 in Valenciennes, a city that in 1678 was French territory but previously had been Flemish. He was also a friend of annother genius painter, Jean Antoine Watteau (1684-1721).

Vanmour was only 28-years old when he went for the first time to Istanbul in 1699. His first master was the French Ambassador in Istanbul, Charles de Ferriol. It was Ferriol’s idea to stimulate Vanmour, to paint portraits and costumes of the Balkans and the Orient, wedding scenes, funerals and the dancing of dervish. Vanmour decided to live in Istanbul for the rest of his life, perhaps to become one of the most famous painters in Istanbul.

His second master was the Dutch Ambassador in Istanbul, Cornelis Calkoen. Vanmour added to his creativity an additional feature of images of diplomatic life in Istanbul. Ambassador Calkoen met again with the Sultan on September 14th 1727. At that time, the Dutch Republic had extended its dominions in the world and the Orient, by developing an intense and unprecedented trade. The Ottoman Empire had large trade interests with the Netherlands. Diplomatic relations between the two empires had existed since 1612.

Ambassador Calkoe n had an important impact on the court of the Sultan. He took cultural notes at the diplomatic level. But most importantly, he insisted that Vanmour make cyclical paintings.

n had an important impact on the court of the Sultan. He took cultural notes at the diplomatic level. But most importantly, he insisted that Vanmour make cyclical paintings.

It is estimated that Vanmour produced around 65 works, which became part of Rijk’s permanent exhibition in 1902. The majority of his works form the series of costume paintings that include motifs from Albania, Armenia, Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, Persia, Turkey and western Europe. At the time, the Ottoman Empire enjoyed a climate of tolerance in which everyone was free to practice his or her own religion – as long as taxes were paid and civil peace was maintained.

Calkoen had collected all of Vanmour’s paintings and donated them during his lifetime to the board of the Levantine Trade Company. The directors hung the paintings in the Amsterdam Town Hall.

In these 65 works, ten paintings are associated with motifs that reflect the Albanian world. What first caught my eye was the painting called “Albanian soldier” made during the years 1700-1737, which constitutes the true portrait of a warrior’s robes and weapons at the start of the XVIII century. Notice the distinctive long gun, which he holds with his right hand.

More surprising is a painting that represents an Albanian shepherd, who holds in his head a typical hat that can be compared to the hats of the shepherds painted by the great Albanian iconographer Onufri in the XVI century.

But, Vanmour’s masterpiece is a bigger painting with dimensions of 120 x 90 cm, which reflects the uprising of a remarkable historical character of Albanian origin, called Padrona Halili. Halili headed a formidable uprising in the year 1730 that terrified all the Ottoman Empire. This uprising echoed internationally. Appalled the Sultan Ahmed III abdicated the throne to his nephew Mahmud I (1730-1754). Interestingly, Vanmour painted the Albanian rebel with his right hand raised holding a sword and with a triumphant appearance. In Vanmour’s collection was also a second painting depicting the death of Halili. Both paintings were made in the time frame 1730-1737.

Ambassador Calkoen ended his diplomatic service in Istanbul on May 7th 1744 but he continued to be a major Dutch diplomat. In 1737, he negotiated a peace treaty between the Sultan and the Russian Tsar. He traveled to Dresden, Saxony and Poland and died on March 2nd 1764.

The collection of paintings he owned gained fame all over Europe. In 1737, Mercure de France published an article on his collection, especially on Vanmour’s reflective and descriptive art. In Albania, this collection remains largely unknown. In fact, the collection of paintings with Albanian motifs remains undocumented according to specific scientific criteria to become circulated in the science of art history.

Vanmour was one the most prominent European painters of the 18th century and has the merit that he was probably the first European painter who painted cycles of Albanian motifs and portraits in the first half of the 18th century.

It is known that after, and especially in the 19th century, there are numerous European artists who painted in powerful and exotic way Albanian motifs, and it could be said that they have created a sui generis iconography of Albania and Albanians in European art.

Epidamn Zeqo holds an MSc in European Political Economy from the London School of Economics and a dual MA in International Relations and Modern History from the University of St. Andrews. Mr. Zeqo has worked as a Research Analyst for Equiteq LLP and International Business and Diplomatic Exchange. A native of Albania, he lives and works in London.