Britons Look East

April 17, 2012 -

Adam Reichardt

-

News Briefs

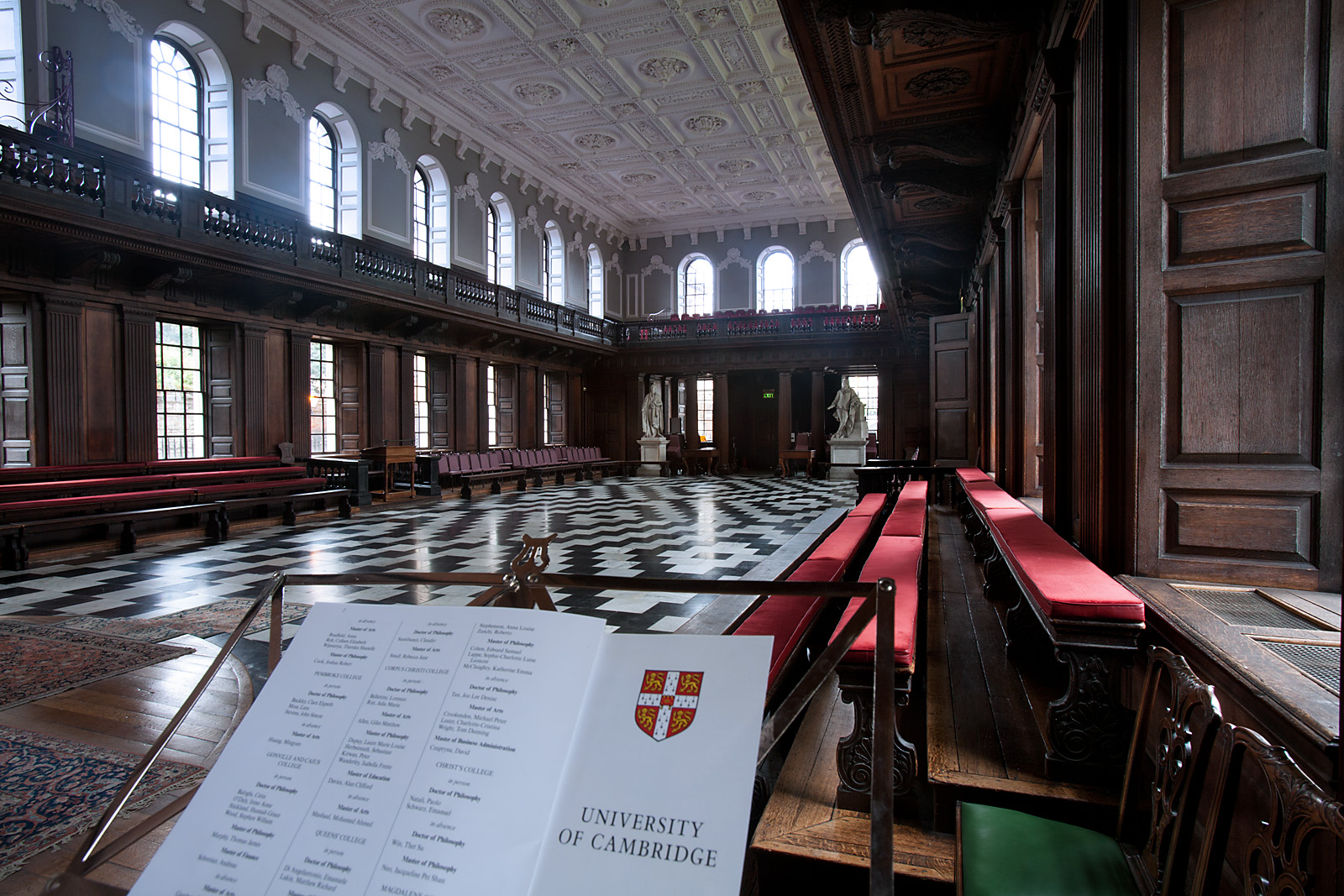

Cambridge_-_University_of_Cambridge_-_1355.jpg

A Review of the Annual Conference of the British Association for Slavonic and Eastern European Studies. March 30 – April 2, 2012. Cambridge, United Kingdom.

The United Kingdom is nearly as far “western Europe” as one can think. Yet, don’t let their geographic position fool you. This year’s annual conference of the British Association for Slavonic and Eastern European Studies (BASEES), held between March 30th to April 2nd 2012, illustrated that when it comes to Central and Eastern Europe, they are right in the middle of what's happening in the region.

What is very unique about the BASEES conference is that it not only focuses on political or current events of the region but encompasses a wide array of fields: from politics, economics, history, literature, culture, sociology, gender studies, film studies, linguistics, and much more. In one conference it is possible to learn about the construction of Czech national mythology through television, the Polish migration to the United Kingdom, the intricacies of Belarusian translation, development of Russian musical institutions after 1917, and the economic impact of the Global financial crisis in Ukraine. The only downside to this event was that there were so many interesting sessions happening at the same time that it was impossible to attend them all, and many gems were surely missed.

One of the highlights of the conference was the opening keynote provided by Ivan Krastev, Editor-in-Chief of the Bulgarian Edition of Foreign Policy, and Chairman of the Centre for Liberal Strategies in Sofia, Bulgaria. Krastev focused his discussion on Eastern Europe in the framework of Europe’s financial crisis. Krastev noted that Europe is now entering a new phase of “Post-democratic capitalism” where decisions made on economic policies are now taken outside of democratically-elected state institutions. He argued that our classical view on how democratic societies function is fundamentally changing and that politicians in Europe are now speaking to two separate “constituencies” – the electorate and the finance sector, adding that the message to these two constituencies are the exact opposite.

Krastev said it was difficult to compare the situation in South Europe to that of the transitions of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. However, he added that it might be interesting to see if the Central/Eastern European model and experience of transition could provide any lessons to those currently in crisis.

Krastev also noted that the most significant difference between the Central/East European countries and those currently in crisis is where the public trust lies. During the transition (and even today in many cases), the public in the transition countries trusted European institutions much more so than their own national institutions and politicians. Whereas in southern Europe it is not the same – citizens of Greece, for example, do not trust the European institutions and their mandates which accompany the financial bailouts and policies. Krastev concluded by saying that in times of crisis it is necessary to maximize flexibility and minimize rigidity.

Another major highlight for the conference was the screening of the documentary film, My Perestroika. The film was directed by American film-maker Robin Hessman. Hessman is no stranger to Russia, as she spent eight years in Moscow working for Russian television. The film follows the story of five individuals who were born during the early 1970s, witnessed the changes in Russia and reflect on not only those changes but also the current situation in Russia. Each of the main characters went to the same primary school and are now all grown up – in very different situations.

The result of Hessman’s work is the captivating story of these five individuals, Borya, Lubya, Olga, Ruslan and Andrei, and their interconnectedness with history in Moscow. The audience is left to reflect on what it must have been like to live through the collapse of the Soviet Union and the transition to a market-based economy. We witness the many dreams and nostalgia that was felt for the Soviet period and the realities they now face. Especially emotional was the story of Ruslan, a musician who was a founding member of the Russian punk group NAIV (Наив). He left the band in 2000, stopped working and was kicked out by his wife kicked. Now considering himself to be “outside society” we are introduced to Ruslan as he takes his eight year old son to Pizza Hut in Moscow. His son explains that he is feeling sad because he has no friends in school. His father tries to assure him, but the same sadness can be seen in Ruslan as well.

The film intertwines the stories and images of these five characters’ life from the past and the present, and the audience is given a spectacular look into what it means to live in Moscow before, during and after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Ruslan with his son: from the film My Perestroika (courtesy Red Square Productions)

The idea of images and nostalgia in Russia carried into the following keynote lecture given by Catriona Kelly of Oxford University. Kelly’s lecture showed us how to understand the post-Soviet transformation in how Russia treats its buildings and moves monuments, or changes the names of streets. She also discussed the idea of studying “mundane” memory and “traumatic” memory in understanding how Russians look back at their own recent history.

Other highlights from the conference included a deep discussion on how to analyse data from the recent Russian elections and the ongoing protest movement, and Stephen White’s (University of Glasgow) conclusions that the data suggests that among Russians using social media, Facebook (not Twitter) was the most influential social media instrument in organising protests.

A presentation by New Eastern Europe contributor, Kelly Hignett (University of Swansea), discussed crime and criminality in Eastern Europe under communism which included research from Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic, which will be published in a forthcoming book due out some time next year.

Lastly, a discussion on the future of energy security and the role of Gazprom in Europe led to an online continuation via our web site: www.neweasterneurope.eu/node/271.

Leaving BASEES, one is left with the overwhelming impression that the major academic programmes in the United Kingdom are doing a considerable amount of research that not only contributes to the West’s understanding of the region, but should be of great interest to researchers and experts on this side of the continent. Making sure that this research is published and disseminated remains an obvious challenge for many them. At the very least, the annual BASEES conference provides the opportunity for these researchers, young and old, to present their answers to the question: What does the past, present and future of Central and Eastern Europe hold?

Adam Reichardt is the Managing Editor of New Eastern Europe, a quarterly journal dedicated to Central and Eastern European affairs based in Krakow, Poland.